About

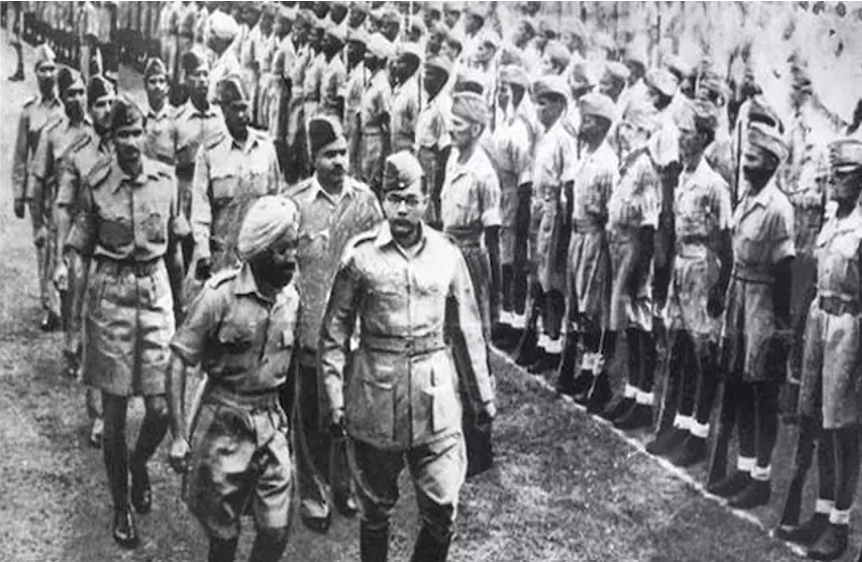

- The Indian National Army (Azad Hind Fauj/ Free Indian Army) was a fortified force formed by Indian collaborationists and Imperial Japan on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. It was formed to secure Indian independence from British rule. It fought alongside Japanese dog faces in the latter’s crusade in the Southeast Asian theatre of WWII. The army was first formed in 1942 under Rash Behari Bose, the British-Indian Army captured by Japan in the Malayan crusade and at Singapore. This first INA collapsed and was disbanded in December that time after differences between the INA leadership and the Japanese service over its part in Japan’s war in Asia. Rash Behari Bose handed over INA to Subhas Chandra Bose. It was revived under the leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose after his appearance in Southeast Asia in 1943. The army was declared to be the army of Bose’s Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind (the Provisional Government of Free India). Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose named the armies/ paratroops of INA after Gandhi, Nehru, Maulana Azad, and himself. There was also an all-women troop named after Rani of Jhansi, Lakshmibai. Under Bose’s leadership, the INA drew captures and thousands of greedy assessments from the Indian aboriginal population in Malaya (present-day Malaysia) and Burma. This alternate INA fought along with the Imperial Japanese Army against the British and Commonwealth forces in the juggernauts in Burma at Imphal and Kohima, and latterly against the Allied recovering of Burma.

Role Of Subhash Chandra Bose In INA

Subhas Chandra Bose was the ideal person to lead a recusant army into India came from the veritably morning of F Kikan’s work with captured Indian dogface’s joined the Gandhian movement after relinquishing from a prestigious post in the Indian Civil Service in 1922, snappily rising in the Congress and being confined constantly by the Raj. By the late 1920s, he and Nehru were considered the unborn leaders of Congress. In the late 1920s, he was amongst the first Congress leaders to call for complete independence from Britain (Purna Swaraj), rather than the former Congress ideal of India getting a British dominion. In Bengal, he was constantly indicted by Raj officers for working with the revolutionary movement. Under his leadership, the Congress youth group in Bengal was organized into a quasi-military organization called the Bengal Levies. Bose deplored Gandhi’s pacifism; Gandhi dissented with Bose’s competitions with the Raj. The Congress’s working commission, including Nehru, was generally pious to Gandhi. While openly concurring with Gandhi, Bose won the administration of the Indian National Congress doubly in the 1930s. His alternate palm came despite opposition from Gandhi. He defeated Gandhi’s favored seeker, Bhogaraju Pattabhi Sitaramayya, in the popular vote, but the entire working commission abnegated and refused to work with Bose. Bose abdicated from the Congress administration and innovated his own body, the All India Forward Bloc.

Bose meeting with Adolf Hitler in East Prussia, May 1942. At the launch of World War II, Bose was placed under house arrest by the Raj. He escaped by disguise and made his way through Afghanistan and Central Asia. He came first to the Soviet Union and also to Germany, reaching Berlin on 2 April 1941. There he- sought to raise an army of Indian dogfaces from captures of war captured by Germany, forming the Free India Legion and the Azad Hind Radio. The Japanese minister, Oshima Hiroshi, kept Tokyo informed of these developments. From the very launch of the war, the Japanese intelligence services noted from speaking to captured Indian dog faces that Bose was held in extremely high regard as a nationalist and was considered by Indian dogfaces to be the right person to be leading the recusant army.

Relation With Other Armies And Operations Performed

- The army’s relationship with the Japanese was an uncomfortable bone. Officers in the INA doubted the Japanese. Leaders of the first INA sought formal assurances from Japan before the war. When these didn’t arrive, Mohan Singh abdicated after ordering his army to disband; he anticipated being doomed to death. After Bose established Azad Hind, he tried to establish his political independence from the government that supported him. Indeed, he’d led demurrers against the Japanese expansion into China and supported Chiang Kai-shek during the 1930s. As the ad Hind depended on Japan for arms and material but sought to be as financially independent as possible, levying levies and raising donations from Indians in Southeast Asia”. On the Japanese side, members of the high command had been tête-à-tête impressed by Bose and were willing to grant him some latitude; more importantly, the Japanese were interested in maintaining the support of a man who had been suitable to mobilise large figures of Indian deportees – including, most importantly, of the Indians captured by the Japanese at Singapore. Still, Faye notes that relations between dogfaces in the field were different. Attempts to use Shah Nawaz’s colours in road structure and as janitors infuriated the colours, forcing Bose to intermediate with Mutaguchi. After the pullout from Imphal, the relations between both inferior non-commissioned officers and between elderly officers had deteriorated. INA officers accused the Japanese Army high command of trying to deceive INA colours into fighting for Japan. Again, Japanese dogfaces frequently expressed misprision for INA dogfaces for having changed their pledge of fidelity. This collective dislike was especially strong after the pullout from Imphal began; Japanese dogfaces, suspicious that INA deserters had been responsible for their defeat, addressed INA dogfaces as” shameless bone” rather of” comrade” as preliminarily had been the case. Azad Hind officers in Burma reported difficulties with the Japanese military administration in arranging forces for colours and transport for wounded men as the armies withdrew. Toye notes that original IIL members and Azad Hind Dal ( original Azad Hind executive brigades) organised relief inventories from Indians in Burma at this time. As the situation in Burma came hopeless for the Japanese, Bose refused requests to use INA colours against Aung San’s Burma National Army, which had turned against Japan and was now confederated with Commonwealth forces.

Controversies And Hard Work Of Great Personalities In INA

British and Commonwealth colours viewed the rookies as serpents and Axis collaborators. Nearly Indian dogfaces in Malaya didn’t join the army and remained as PoWs. Numerous were transferred to work in the Death Road, suffered rigours and nearly failed under Japanese immurement. Numerous of them cited the pledge of constancy they had taken to the King among reasons not to join a Japanese- supported organisation and regarded the rookies of the INA as serpents for having abandoned their pledge. Commanders in the British-Indian Army like Wavell later stressed the rigours this group of dogfaces suffered, differing them with the colours of the INA. Numerous British dogfaces held the same opinion., Hugh Toye and Peter Fay point out that the First INA comported of a blend of rookies joining for colourful reasons, similar as nationalistic leanings, Mohan Singh’s prayers, particular ambition or to cover men under their command from detriment. Fay notes some officers like Shah Nawaz Khan were opposed to Mohan Singh’s ideas and tried to hamper what they considered a collaborationist organisation. Still, both chroniclers note that Indian civilians and former INA dogfaces all cite the tremendous influence of Subhas Bose and his appeal to nationalism in invigorating the INA. Fay discusses the content of fidelity of the INA dogfaces and highlights that in Shah Nawaz Khan’s trial it was noted that officers of the INA advised their men of the possibility of having to fight the Japanese after having fought the British, to help Japan from exploiting post-war India. Carl Vadivella Belle suggested in 2014 that among the original Indians and British-Indian Army levies in Malaya, there was a proportion who joined due to the trouble of conscription as Japanese labour colours. Reclamation also offered original Indian labourers security from semi-starvation of the estates and served as a hedge against Japanese despotism.

- INA colours were contended to engage in or be complicit in the torture of Allied and Indian captures of war. Fay in his 1993 history analyses war-time press releases and field counter-intelligence directed at Sepoys. He concludes that the Jiffs crusade promoted the view that INA rookies were weak-conscious and treacherous Axis collaborators, motivated by selfish interests of rapacity and particular gain. He concludes that the allegations of torture were largely products of the Jiffs crusade. He supports his conclusion by noting that insulated cases of torture had passed, but allegations of the widespread practise of torture weren’t substantiated in the charges against defendants in the Red Fort trials. Published biographies of several stages, including that of William Slim, portray the INA colours as unable fighters and as untrustworthy. Toye noted in 1959 that individual derelictions passed in the pullout from Imphal. Fay concluded that stories of INA derelictions during the battle and the original retreat into Burma were largely inflated. The maturity of derelictions passed much later, according to Fay, around the battles at Irrawaddy and latterly around Popa. Fay specifically discusses Slim’s depiction of the INA, pointing out what he concludes to be inconsistencies in Slim’s accounts. He concludes the opinions held by Commonwealth war stagers similar to Slim were an inaccurate depiction of the unit, as were those of INA dogfaces themselves. Indian activists like Samar Guha, chroniclers like Kapil Kumar, as well as Indian parliamentarians, purport that sanctioned histories of the independence movement largely forget events girding the INA – especially the Red Fort trials and the Bombay Insurgency – and ignore their significance in invigorating the independence movement and guiding British opinions to relinquish the Raj. A history of the army and Azad Hind, written by Indian annalist Pratul Chandra Gupta in the 1950s at the request of the Indian Government, was latterly classified and not released until 2006. Further examinations have been made in recent times over the denial till the 1980s of the” freedom fighter’s pension” awarded to those in the Gandhian movement, and over the general rigours and apathy girding the conditions of former INA dogfaces.

INA After 1947

Within India, the INA continues to be an emotive and famed subject of discussion. It continued to have a fort over the public psyche and the sentiments of the fortified forces until as late as 1947. It has been suggested that Shah Nawaz Khan was assigned with organizing INA colors to train Congress levies at Jawaharlal Nehru’s request in late 1946 and early 1947. After 1947, several members of the INA who were nearly associated with Subhas Bose and with the INA trials were prominent in public life. Mohan Singh was elected to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament. He worked for the recognition of the members of the Indian National Army as “freedom fighters” in the cause of the nation’s independence in and out of Parliament. Shah Nawaz Khan served as Minister of State for Rail in the first Indian press. Lakshmi Sahgal, Minister for Women’s Affairs in the Azad Hind government, was a well-known and extensively reputed public figure in India. In 1971, she joined the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and was latterly tagged the leader of the All India Democratic Women’s Association. Joyce Lebra, an American annalist, wrote that the revivification of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, also a fledgling Tamil political party in southern India, would not have been possible without the participation of INA members.

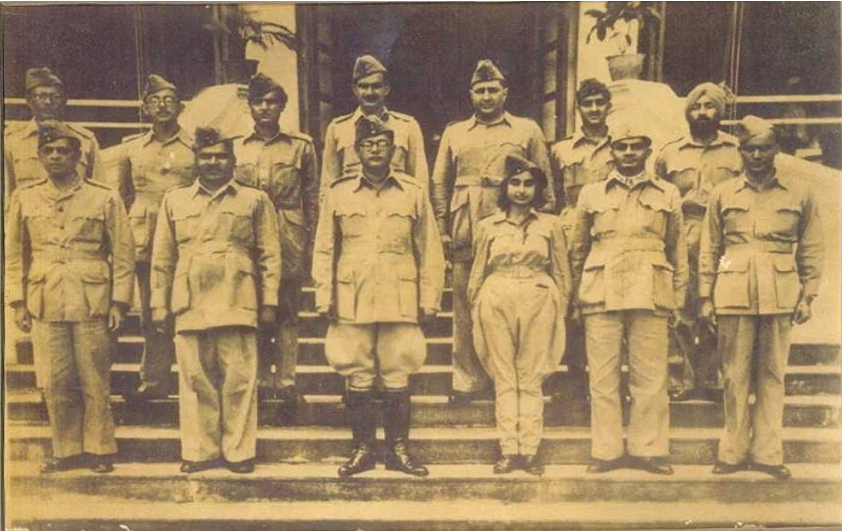

Lakshmi Sahgal in an afterlife, at a political meeting in India. Some accounts suggest that the INA stagers were involved in training mercenary resistance forces against the Nizam’s Razakars previous to the prosecution of Operation Polo and the annexation of Hyderabad. There are also suggestions that some INA stagers led Pakistani irregulars during the First Kashmir War. Mohammed Zaman Kiani served as Pakistan’s political agent to Gilgit in the late 1950s. Of the veritably many ex-INA members who joined the Indian Armed Forces after 1947R.S. Benegal, a member of the Tokyo Boys joined the Indian Air Force in 1952 and latterly rose to be an air commander. Benegal saw action in both the 1965 and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, earning a Maha Vir Chakra, India’s alternate-loftiest award for valor.

Among other prominent members of the INA, Ram Singh Thakur, musician of several songs including the INA’s regimental march Kadam Kadam Badaye Ja, has been credited by some for the ultramodern tune of the Indian public hymn.

Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon and Lakshmi Sahgal were latterly awarded the Indian mercenary honors of Padma Bhushan and Padma Vibhushan independently by the Indian Government in the 1990s. Lakshmi Sahgal was nominated for the Indian presidential election by communist parties in 2002. She was the sole opponent ofA.P.J. Abdul Kalam, who surfaced victoriously. Subhas Bose himself was posthumously awarded Bharat Ratna in 1992, but this was latterly withdrawn over the contestation over the circumstances of his death

End Of INA And Formation Of Indian Army

INA captures who were falling into Allied hands were being estimated by encouraging intelligence units for implicit trials. Nearly fifteen hundred had been captured in the battles of Imphal and Kohima and the posterior pullout, while larger figures surrendered or were captured during the 14th Army’s Burma Campaign. An aggregate of the INA’s rookies was captured, of whom around were interrogated by the Combined Services Directorate of Investigation Corps (CSDIC). The number of captures needed this picky policy which anticipated trials of those with the strongest commitment to Bose’s testaments. Those with lower commitment or other extenuating circumstances would be dealt with further leniently, with the discipline commensurable to their commitment or war crimes.

By July 1945, a large number had been packed back to India. While the downfall of Japan, the remaining captured colors were transported to India via Rangoon. Large figures of original Malay and Burmese levies, including the rookies to the Rani of Jhansi troop, returned to mercenary life and weren’t linked. Those repatriated passed through conveyance camps in Chittagong and Calcutta to be held at detention camps each over India including Jhingergacha and Nilganj near Calcutta, Kirkee outside Pune, Attock, Multan, and at Bahadurgarh near Delhi. Bahadurgarh also held captures of the Free India Legion. By November, around INA captures were held in these camps; they were released according to the”colors”. By December, around 600 Whites were released per week. The process to elect those to face trial started.

The British-Indian Army intended to apply applicable internal correctional action against its dogfaces who had joined the INA, whilst putting to trial a named group to save discipline in the Indian Army and to award discipline for felonious acts where these had passed. As news of the army spread within India, it began to draw wide they are started giving sympathy support. Review reports around November 1945 reported prosecutions of INA colors, which worsened the formerly unpredictable situation. Decreasingly violent competitions broke out between the police and protesters at the mass rallies being held each over India, climaxing in public riotings in support of the INA men. The Indian National Congress and the Muslim League both made the release of the capture of INA an important political issue during the crusade for independence in 1945 – 1946. Lahore in Diwali 1946 remained dark as the traditional earthen lights lit on Diwali weren’t lit by families in support of captures. In addition to mercenary juggernauts of non-cooperation and non-violent kick, the kick spread to include insurgencies within the British-Indian Army and sympathy within the British-Indian forces. Support for the INA crossed collaborative walls to the extent that it was the last major crusade in which the Congress and the Muslim League aligned together; the Congress tricolor and the green flag of the League were flown together at demurrers.

The Congress snappily came forward to defend dogfaces of the INA who were to be court-martially the INA Defence Committee was formed by the Indian Congress and included prominent Indian legal numbers, among whom were Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai, Kailashnath Katju, and Asaf Ali. The trials covered arguments grounded on military law, indigenous law, transnational law, and politics. Mithi Mukherjee calls the trials a” crucial moment in the elaboration of an anti-coan anti notice of transnational law in India.” Important of the original defense was grounded on the argument that they should be treated as captures of war as they weren’t paid mercenaries but bona fide dogfaces of a legal government – Bose’s Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind. Nehru argued that” still misinformed or else they had been in their notion of nationalistic duty towards their country”, they honored the free Indian state as their autonomous and not the British sovereign. Peter Fay points out that at least one INA internee – Burhan-ud-Din a family of the sovereign of Chitral – may have merited to be indicted of torture, but his trial had been remitted on executive grounds. Those charged after the first famed courts-martial only faced trial for torture and murder or assist of murder. Charges of disloyalty were dropped for fear of inflaming public opinion.

In malignancy of aggressive and wide opposition to the durability of the court-martial, it was completed. All three defendants were planted shamefaced in numerous of the charges and doomed to expatriation for life. The judgment, still, was noway carried out. Immense public pressure, demonstrations, and screams forced Claude Auchinleck to release all three defendants. Within three months, dogfaces of the INA were released after terminating and penalty of pay and allowance. On the recommendation of Lord Mountbatten and with the agreement of Jawaharlal Nehru, former dogfaces of the INA weren’t allowed to join the new Indian Armed Forces as a condition for independence.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About INA

-

The Indian government, and his so-called Indian National Army (Azad Hind Fauj), alongside Japanese colors, advanced to Rangoon (Yangon) and thence overland into India, reaching Indian soil on March 18, 1944, and moving into Kohima and the plains of Imphal.

-

The Azad Hind Fauj was first established by Captain-General Mohan Singh in Singapore in 1942 but was latterly disbanded. With the help of Indians living in Southeast Asia, Bose revived the INA and assumed charge of it.

-

Subhas Chandra Bose was born on January 23, 1897, in Cuttack, also a part of Bengal Province’s Orissa Division. After finishing his academy education, he compactly studied at Presidency College. He latterly studied gospel at Scottish 4. Church College, University of Calcutta and also went to study in Britain.

-

Subhas Chandra Bose qualified for the prestigious Indian Civil Services Examination (ICS). Still, he soon quit as he didn’t want to work under the British government.

-

Bose joined the Independence movement and came to be a member of the Congress party. He, still, had major ideological differences with leading numbers like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawahar Lal Nehru. A radical leader in Congress, he came the President of the party in 1938 but was ousted after differences with Gandhi and the party’s high command. He differed with Mahatma Gandhi’s styles of non-violence and wanted to wage war against our social autocrats.

-

The Indian National Army nonetheless for some time succeeded in maintaining its identity as an emancipation army, grounded in Burma and also Indochina. With the defeat of Japan, still, Bose’s fortunes ended.

-

Netaji Subhas Chandra made his’ great escape from his ancestral house in Kolkata in 1941 when he was under house arrest by the also British government. He made his way to the Soviet Union and also to Germany.

-

On October 21, 1943, Bose assumed charge of the Supreme Command of the INA and blazoned the proclamation of the Azad Hind Government. A great lecturer, Netaji gave a clarion call of independence with his notorious‘ Give me blood, and I shall give you freedom!’ speech. The speech was made in Burma in 1944 to members of the Indian National Army.

-

INA disaccorded with the British forces around Imphal and Kohima in 1944. Britain’s struggle to repel a concerted force of Netaji- led INA and Japan during World War II, around Imphal and Kohima in 1944 has been arbitrated as the’ topmost ever battle involving British forces in a contest run by the National Army Museum in London.

-

A classified 60- time-old Japanese government document on Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s death made public on Thursday concludes that the fabulous freedom fighter failed in an airplane crash in Taiwan on 18 August 1945, backing the sanctioned interpretation.

-

Every time on 21 October, the anniversary of the confirmation of the Azad Hind Government is celebrated across the country. On this day, India’s first independent provisional government named Azad Hind Government was blazoned. First established in 1942 by Mohan Singh, Azad Hind Fauj or the Indian National Army (INA) was revived by Subhas Chandra Bose on 21 October 1943.

-

The Azad Hind Fauj was initiated during World War II to secure complete Indian independence from British rule.

-

It was Generals of the British Indian army (before 1949) and Indian Army (after General Cariappa took over in January 1949) who opposed tooth and nail any concessions for INA help. Both Viceroy Field Marshal Wavell and C-in-C Field Marshal Auchinleck were unwavering in their commitment to take the strongest possible correctional action against the Azad Hind dogfaces. It was a natural response of the generals as the dogfaces of the regular army and INA were on contrary sides. Still, the political leaders of the day, especially Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, and latterly Indira Gandhi having the capacity to see the‘ bigger picture and appreciate public sentiments took the right opinions in favour of the stalwart officers and men of the INA. Gen. Mohan Singh acknowledges this in his magnum number.