- Umang Sagar

- History, Recent article

Two Nation Theory

Introduction

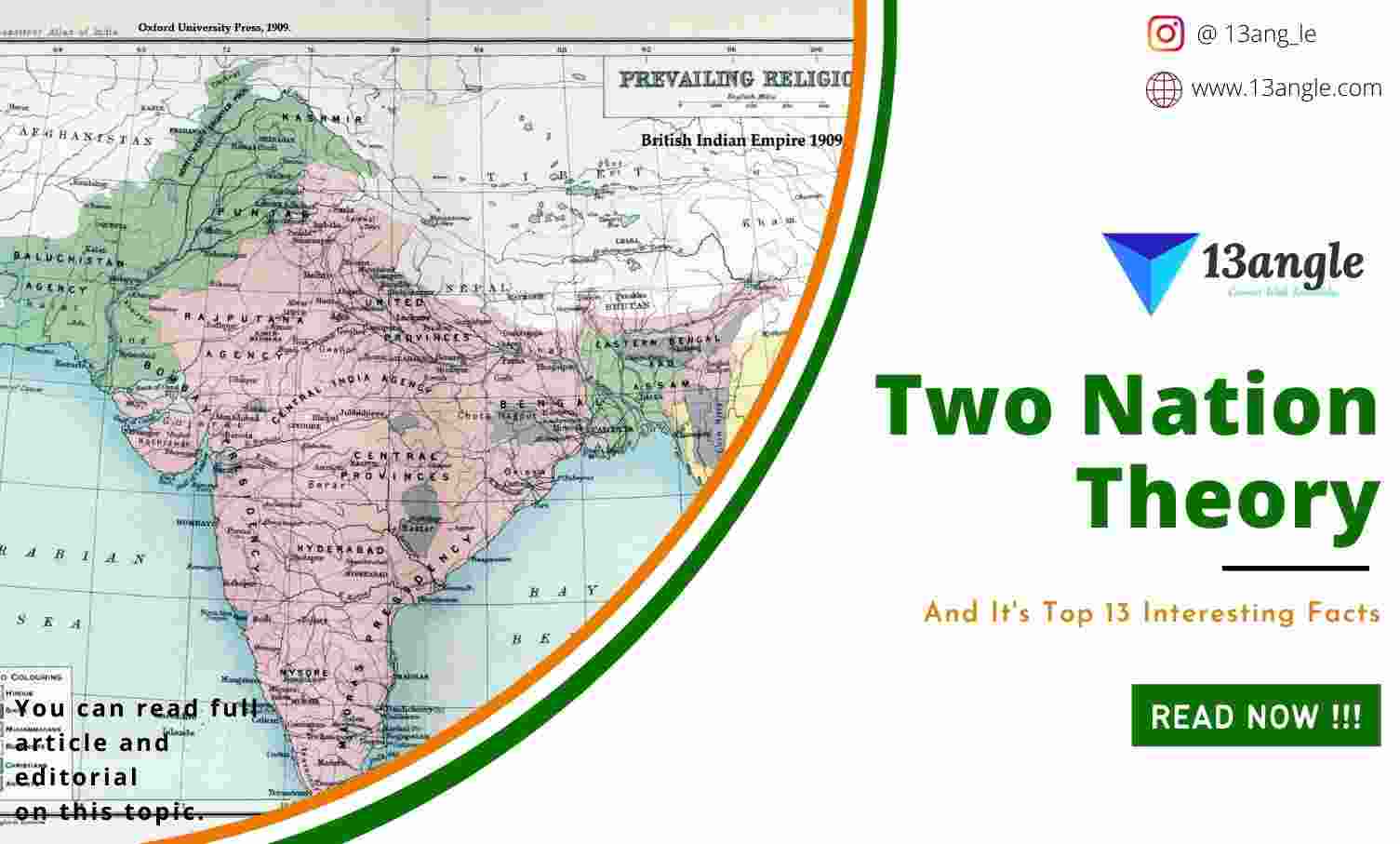

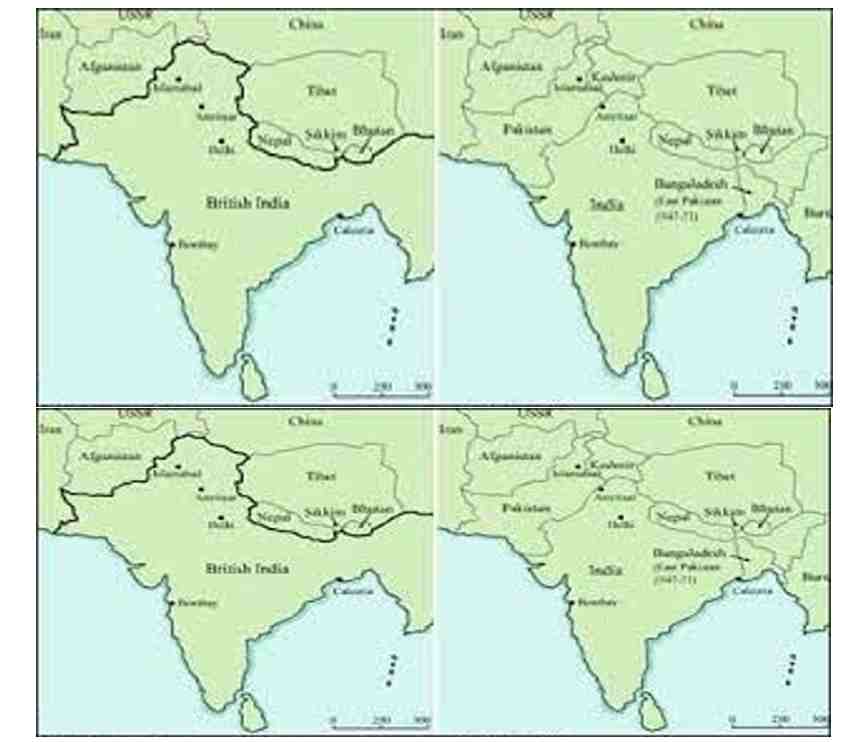

The two-nation theory is a religious nationalism doctrine that had a great impact on the Indian subcontinent after it gained independence from the British Empire. According to this theory, Indian Muslims and Indian Hindus are two separate nations, each with its own customs, religion, and traditions. As a result, Muslims should be able to have their own separate homeland outside of Hindu-majority India, where Islam is the dominant religion, and be separated from Hindus and other non-Muslims from a social and moral standpoint. The All India Muslim League’s two-nation theory was the fundamental idea of the Pakistan Movement (i.e., the ideology of Pakistan as a Muslim nation-state in India’s northwestern and eastern parts) after India’s partition in 1947.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah promoted the idea that religion is the primary element in establishing the nationality of Indian Muslims, referring to it as the “waking of Muslims” for the establishment of Pakistan. It also serves as a source of inspiration for a number of Hindu nationalist organizations, with causes ranging from the reclassification of Indian Muslims as non-Indian foreigners and second-class citizens in India to the expulsion of all Muslims from the country, the establishment of a legally Hindu state in India (currently secular), the prohibition of conversions to Islam, and the promotion of conversions or reconversions of Indian Muslims to Hinduism.

The two-nation theory can be interpreted in a variety of ways, depending on whether the two assumed nationalities can live in the same land or not, with dramatically different consequences. One interpretation advocated for the independence of Muslim-majority parts of British India, citing fundamental disparities between Hindus and Muslims; nonetheless, this interpretation promised a democratic state in which Muslims and non-Muslims would be treated equally. A second interpretation maintains that a population transfer (i.e., the whole removal of Hindus from Muslim-majority regions and Muslim-majority areas) is a necessary step toward the final separation of two incompatible countries that “cannot coexist in a peaceful partnership.”

Both nationalist Muslims and Hindus opposed the two-nation doctrine, which was based on two conceptions. The first is the idea of India as a unified nation, with Hindus and Muslims as linked populations. The second source of opposition is the belief that while Indians, Muslims, and Hindus are not one nation, the relatively homogeneous provincial units of the Indian subcontinent are true nations deserving of sovereignty; this viewpoint has been advanced by Pakistan’s Baloch, Sindhi, Bengali, and Pashtun sub-nationalities, with Bengalis seceding from Pakistan after the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 and other separatist movements. India officially rejected the two-nation theory and declared itself a secular state, with religious pluralism and composite nationalism enshrined in its constitution.

History

The British colonial administration and pundits made “it a point of speaking of Indians as the people of India and avoid speaking of an Indian nation” in general. Because Indians were not a nation, they were theoretically incapable of national self-government, which was claimed as a primary rationale for British rule of the country. While some Indian leaders argued that Indians were a single country, others acknowledged that while they were not yet a nation, there was “no reason why they should not evolve into one over time.” Scholars point out that a sense of national identity has always existed in “India,” or the Indian subcontinent more broadly, even if it was not expressed in modern terms.

Indian historians such as Shashi Tharoor have stated that India’s division was caused by the British colonial government’s divide-and-rule policy, which began after Hindus and Muslims banded together to resist the British East India Company in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. At the language, regional, and religious levels in India, similar conflicts about national identity prevailed. Some claimed that Indian Muslims were a single country, while others said that they were not.

Some, such as Liaquat Ali Khan (later Pakistani Prime Minister), felt that Indian Muslims were not yet a country, but might be. Muhammad bin Qasim is generally referred to be the first Pakistani, according to Pakistan’s official chronology. While Prakash K. Singh considers Muhammad bin Qasim’s entry to be the initial step toward the formation of Pakistan. The Pakistan movement, according to Muhammad Ali Jinnah, began when the first Muslim stepped into the Gateway of Islam.

Roots Of Muslim Separatism In Colonial India (17th Century–1940s)

Many Muslims in colonial India recognised themselves as Indian citizens alongside Indians of other religions. These Muslims saw India as their permanent home, having lived there for centuries, and saw it as a multireligious state with a history of peaceful coexistence. Mian Fayyazuddin, a legislator, declared, “We are all Indians, and we share the same Indian-ness.” We demand nothing less than an equitable share since we are equal partners. Forget about minority and majority; these are political constructs used to garner political mileage. Others, on the other hand, began to contend that Muslims were their own country.

In Pakistan, it is widely assumed that the movement for Muslim self-awakening and identity was started by Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624), who fought against Emperor Akbar’s religious syncretist Din-iIlahi movement and is thus considered “for contemporary official Pakistani historians” to be the founder of the Two-nation theory, and was particularly intensified under Muslim reformer Shah Waliullah (1703-1762), who, because he wanted to restore Muslims’ self-citi.

Because of their purist and militant reformist movements targeting the Muslim masses, Akbar Ahmed considers Haji Shariatullah (1781–1840) and Syed Ahmad Barelvi (1786–1831) to be forerunners of the Pakistan movement “Reformers such as Waliullah, Barelvi, and Shariatullah were not calling for a modern-day Pakistan. They did, however, play a key role in raising awareness of the impending Muslim crisis and the need to form their own political organisation. Sir Sayyed’s contribution was to create a modern idiom for expressing the search for Islamic identity.” As a result, many Pakistanis regard Syed Ahmad Khan (1817–1898), a modernist and reformist thinker, as the father of the two-nation doctrine.

Sir Syed, for example, spoke of two separate countries in a January 1883 address in Patna, even if his personal approach was conciliatory: Friends, in India, there are two significant nations, Hindus and Mussulmans, who are distinguishable by their names. These two nations are analogous to the primary limbs of India, much as a man has several major organs. [32] However, he rejected composite Indian nationalism because the formation of the Indian National Congress was seen as a political threat. In a lecture in 1887, he remarked, “Now, suppose all the English left India—who would be the rulers of India?” Is it possible that two nations, Mohammedan and Hindu, could sit on the same throne and share power in these circumstances? Without a doubt, It is necessary for one of them to conquer and subjugate the other. To hope that both could remain equal is to desire the impossible and inconceivable. In 1888, in a critical assessment of the Indian National Congress, which promoted composite nationalism among all the castes and creeds of colonial India, he also considered Muslims to be a separate nationality among many others: The Indian National Congress’s goals and objectives are based on a lack of understanding of history and current politics; they ignore the fact that India is home to a diverse population of nationalities; and they assume that Muslims, Marathas, Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Banias, Sudras, Sikhs, Bengalis, Madrasis, and Peshawaris can all be treated equally and belong to the same nation. Congress believes they share the same faith, speak the same language, and have the same way of life and practises… I believe that the experiment proposed by the Indian National Congress is laden with perils and misery for all Indian nations, particularly Muslims.

Justice Abdur Rahim (1867–1952) was one of the first to openly articulate how Muslims and Hindus form two nations in 1925, during the Aligarh session of the All-India Muslim League, which he chaired, and while it would later become common rhetoric, historian S. M. Ikram says it “created quite a sensation in the twenties”: “The Hindus and Muslims are not two religious sects like the Protestants and Catholics of England, but form two distinct common. Their distinct attitudes toward life, culture, civilization, and social habits, as well as their traditions and history, as well as their religion, divide them so profoundly that the fact that they have lived in the same country for nearly 1,000 years has done little to help them unite as a nation… Any of us Indian Muslims travelling in Afghanistan, Persia, and Central Asia, for example, amid Chinese Muslims, Arabs, and Turks, would feel right at home and would not encounter anything unfamiliar. In India, on the other hand, when we cross the street and reach the section of town where our Hindu neighbours dwell, we find ourselves absolute strangers in all social affairs. The poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938) offered the philosophical explication, and Barrister Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1871–1948) turned it into the political actuality of a nation-state, more significantly and influentially than Justice Rahim or the historiography of British administrators. Some consider Allama Iqbal’s presidential address to the Muslim League on December 29, 1930, to be the first formal presentation of the two-nation theory in favour of what would become Pakistan. In its endeavour to represent Indian Muslims, the All-India Muslim League believed that the Muslims of the subcontinent constituted a unique and independent country from the Hindus. They requested separate electorates at first, but when they realised that Muslims would be unsafe in a Hindu-dominated India, they desired a separate state. The League wanted self-determination for Muslim-majority areas in the form of a sovereign state that guaranteed minorities in these Muslim-majority areas equal rights and protections. Many experts believe that an elite class of Muslims in colonial India organised the establishment of Pakistan through the partition of India, rather than the average man.

A vast number of Islamic political parties, religious schools, and organisations opposed India’s partition and called for a composite nationalism that included all Indians in resistance to British authority (especially the All India Azad Muslim Conference). According to a CID report from 1941, hundreds of Muslim weavers from Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh descended on Delhi under the guise of the Momin Conference to protest the projected two-nation doctrine. At the time, a meeting of more than 50,000 individuals from an unorganised sector was unusual, thus its significance should be recognised. The majority of Indian Muslims, non-ashraf Muslims, were opposed to partition, but their voices were not heard.

They were devout Muslims, yet they were hostile to Pakistan. On the other hand, Ian Copland, in his book about the end of British rule in the Indian subcontinent, clarifies that it was not solely an élite-driven movement that spawned separatism “as a defence against the threats posed to their social position by the introduction of representative government and competitive recruitment to the public service,” but that the Muslim masses were heavily involved due to religious polarisation.”The fact that some of the loudest spokesmen for the Hindu cause and some of the biggest donors to the Arya Samaj and the cow protection movement came from the Hindu merchant and money lending communities, the principal agents of lower-class Muslim economic dependency, reinforced this sense of insecurity,” and “each year brought new riots” because of Muslim resistance, so that “by the end of the century, Hindu-Muslim relations had become so soured by this deadly roun,”

Opposition To The Partition Of India

1. All India Azad Muslim Conference:-

- In April 1940, the All-India Azad Muslim Conference, which represented nationalist Muslims, met in Delhi to express support for a unified and independent India. The British administration, on the other hand, ignored this nationalist Muslim group and came to see Jinnah, a separatist, as India’s sole representative.

2. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan And The Khudaikhidmatgar

- Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, popularly known as “Frontier Gandhi” or “Sarhadi Gandhi,” was not convinced by the two-nation idea and advocated for a single undivided India that would accommodate both Hindus and Muslims. He was from British India’s northwest Frontier Province, which is now Pakistan. He felt that the Indian subcontinent’s Muslims will suffer as a result of the division. Following the controversial referendum in which a majority of NWFP voters chose Pakistan, Ghaffar Khan accepted their decision and took an oath of allegiance to the new country on February 23, 1948, during a session of the Constituent Assembly, and his second son, Wali Khan, “played by the rules of the political system” as well.

3. Mahatma Gandhi's View

- Mahatma Gandhi was an outspoken opponent of religious partition in India. I see no precedent in history for a group of converts and their descendants claiming to constitute a country apart from the parent line, he once wrote.

4. View Of The Deobandi Ulema

- The great majority of Deobandi Islamic religious experts, represented by the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, who backed both the All India Azad Muslim Conference and the Indian National Congress, were adamantly opposed to the two-nation doctrine and India’s partition. Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madni, the head of Darul Uloom Deoband, not only opposed the two-nation doctrine but also tried to redefine Indian Muslim nationhood. He believed that contemporary countries were founded on the basis of geography, culture, and history, and he campaigned for composite Indian nationalism. He and other prominent Deobandi ulama advocated territorial nationalism, claiming that it was permissible under Islam. Despite the criticism of the majority of Deobandi intellectuals, Ashraf Ali Thanvi and Mufti Muhammad Shafi attempted to defend the two-nation theory and notion of Pakistan.

Post-Partition Debate

Since the division, the idea has been the subject of heated disputes and various interpretations for a variety of reasons. Mr. Niaz Murtaza, a Pakistani academic with a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley, asked in his Dawn column on April 11, 2017, “If the two-nation thesis is forever true, why did Muslims migrate from Arabia to Hindu India?” Why did they not create a separate state for Hindus based on this notion and live with and dominate them for centuries? When Hindu control became clear, why did the two-nation notion emerge? All of this can only be justified by an irrational sense of superiority based on a divine entitlement to govern others, which many Muslims still believe in today, despite their poor morals and development. Many ordinary Muslims condemned the two-nation doctrine, claiming that it favored mainly the Muslim elite and resulted in the deaths of almost one million people.

“The two-nation theory, which we had used in the fight for Pakistan, had created not only bad blood against the Muslims of the minority provinces but also an ideological wedge between them and the Hindus of India,” wrote Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, a prominent leader of the Pakistan movement and the first president of the Pakistan Muslim League, in his memoirs Pathway to Pakistan (1961).”He (Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy) questioned the efficacy of the two-nation doctrine, which, to my understanding, had never provided any benefits to us,” he said, “but after the partition, it proved positively damaging to the Muslims of India, and on a long-term basis for Muslims everywhere.”

According to Khaliquzzaman, on August 1, 1947, Jinnah hosted a goodbye gathering at his Delhi home for Muslim League members of India’s constituent legislature. Mr. Rizwanullah raised some uncomfortable issues about Muslims who will be left behind in India, their status, and their destiny. I had never seen Mr. Jinnah so worried as on that day, presumably because he was well aware of what was ahead for the Muslims. I urged my friends and coworkers to halt the conversation since I found the scenario uneasy. I feel that as a result of our farewell meeting, Mr. Jinnah used his first address as governor general-designate and President of Pakistan’s constituent assembly on August 11, 1947, to abandon his two-nation idea. According to Indian nationalists, the British rulers purposefully split India to keep the country weak. Jinnah had spoken of composite Pakistani nationalism in his address on August 11, 1947, thereby contradicting the faith-based nationalism that he had championed in his March 22, 1940 speech. In his August 11 address, he stated that non-Muslims will be treated equally as citizens of Pakistan, with no prejudice. “You may be of any faith, caste, or creed as long as it has nothing to do with the state’s business.”On the other hand, it was mostly tactical, rather than intellectual (the shift from faith-based to composite nationalism). “Excerpts of this speech were widely disseminated,” according to Dilip Hiro, in order to stop communal violence in Punjab and the NWFP, where Muslims and Sikhs-Hindus were butchering each other and which deeply disturbed Jinnah personally, but “the tactic had little, if any, impact on the horrendous barbarity that was being perpetrated on the plains of Punjab.”In an interview, another Indian scholar, Venkat Dhulipala, shows in his book Creating a New Medina that Pakistan was meant to be a new Medina, an Islamic state, and not just a state for Muslims, and that it was ideological from the start with no room for composite nationalism, also says that the speech “was made primarily keeping in mind the tremendous violence that was going on,” that it was “directed at protecting” the country.

“It was pragmatism,” the historian continues, “after all, a few months later, when requested to open the doors of the Muslim League to all Pakistanis irrespective of their faith or creed, the same Jinnah declined, claiming that Pakistan was not ready for it.”Muslims and Hindus did not completely divide, and around one-third of all Muslims remained to reside in post-partition India as Indian citizens alongside a considerably larger Hindu majority. The partition of Pakistan into the present-day countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh was claimed as proof that Muslims did not form a single country and that religion was not a defining feature of nationhood.

Post-Partition Perspectives In India

- India formally rejected the two-nation doctrine and declared itself a secular state, with religious plurality and composite nationalism enshrined in its constitution. Nonetheless, in post-independence India, the two-nation theory aided Hindu nationalist movements in attempting to establish a “Hindu national culture” as an Indian’s essential identity. [requires citation] This permits Indian Hindus and Muslims to have a shared ethnicity but also necessitating that all acquire a Hindu identity in order to be genuinely Indian.According to Hindu nationalists, this acknowledges the ethnic fact that Indian Muslims are “flesh of our flesh and blood of our blood,” but nonetheless pushes for a legally acknowledged equivalence of national and religious identity, i.e., “an Indian is a Hindu.” The argument, as well as the fact that Pakistan exists, has led Indian far-right extremist organisations to claim that Indian Muslims “cannot be loyal citizens of India” or any other non-Muslim country, and that they are “always capable and willing to do treacherous deeds.”India’s constitution rejects the two-nation doctrine and considers Indian Muslims to be equal citizens. Indian politicians such as Shashi Tharoor have asserted that India’s division was the outcome of the British colonial government’s divide-and-rule strategies, which began after Hindus and Muslims banded together to oppose the British East India Company in the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About Two Nation Theory

The two-nation theory is a religious nationalism doctrine that had a great impact on the Indian subcontinent after it gained independence from the British Empire.

According to this theory, Indian Muslims and Indian Hindus are two separate nations, each with its own customs, religion, and traditions.

As a result, Muslims should be able to have their own separate homeland outside of Hindu-majority India, where Islam is the dominant religion, and be separated from Hindus and other non-Muslims from a social and moral standpoint.

The All India Muslim League’s two-nation theory was the fundamental idea of the Pakistan Movement (i.e., the ideology of Pakistan as a Muslim nation-state in India’s northwestern and eastern parts) after India’s partition in 1947.

The British colonial administration and pundits made “it a point of speaking of Indians as the people of India and avoid speaking of an Indian nation” in general.

Because Indians were not a nation, they were theoretically incapable of national self-government, which was claimed as a primary rationale for British rule of the country.

While some Indian leaders argued that Indians were a single country, others acknowledged that while they were not yet a nation, there was “no reason why they should not evolve into one over time.”

Scholars point out that a sense of national identity has always existed in “India,” or the Indian subcontinent more broadly, even if it was not expressed in modern terms.

The two-nation theory, which we had used in the fight for Pakistan, had created not only bad blood against the Muslims of the minority provinces but also an ideological wedge between them and the Hindus of India,” wrote Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, a prominent leader of the Pakistan movement and the first president of the Pakistan Muslim League, in his memoirs Pathway to Pakistan (1961).

“He (Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy) questioned the efficacy of the two-nation doctrine, which, to my understanding, had never provided any benefits to us,” he said, “but after the partition, it proved positively damaging to the Muslims of India, and on a long-term basis for Muslims everywhere.”

India formally rejected the two-nation doctrine and declared itself a secular state, with religious plurality and composite nationalism enshrined in its constitution.

Nonetheless, in post-independence India, the two-nation theory aided Hindu nationalist movements in attempting to establish a “Hindu national culture” as an Indian’s essential identity.

According to Hindu nationalists, this acknowledges the ethnic fact that Indian Muslims are “flesh of our flesh and blood of our blood,” but nonetheless pushes for a legally acknowledged equivalence of national and religious identity, i.e., “an Indian is a Hindu.”