Introduction

The Right to Information is a cornerstone of democratic governance. This right is necessary for the democratic process to work properly. The freedom of speech and expression enshrined in Article 19(1)(A) of the constitution, which is recognized as the fundamental condition of liberty, includes the right to information. It holds a prominent position in the hierarchy of liberties, providing support and protection to others. Article 19(1) has been interpreted to encompass the right to obtain and publish information. It includes the right to transmit it through any accessible medium, whether print, electronic, or audio-visual, such as an advertisement, a movie, an article, or a speech, among other things. This freedom involves the ability to freely communicate or distribute one’s views to as big an audience as possible, both within the country and overseas. The two sides of the same coin are communication and information receipt. The freedom to receive and spread information without restriction is a crucial part of freedom of speech and expression. A person cannot create an informed view without sufficient information.

In a country like India, where the government is made up of a large number of public servants, everyone is responsible for their own actions; therefore there is no place for keeping secrets. The thriving right to information movement in India has considerably empowered ordinary citizens in less than a decade. He may now exert a considerable check on State bureaucrats’ arbitrary use of authority, resulting in the country’s democratic set-up developing. India’s people have long fought for the Constitution and, with it, inalienable fundamental rights. The right to information is also one of the Constitution’s implicit fundamental rights. Because the executive culture in India has been one of secrecy since colonial control, the Fundamental Right to Information is a sine qua non of democracy in India. There has never been consistent and unwavering access to data.

- When information disclosure is requested proactively, it is frequently overlooked or taken lightly. The new law’s enforcement mechanisms are being strained by the increasing number of complaints and appeals. Nonetheless, proponents of the RTI Act, of 2005 have already proved the new law’s potential for transformation, and they are working tirelessly to ensure its correct implementation. Public authorities and civil society organizations have made innovations in practice that could be very useful to other countries considering similar legislation.

Need For RTI In India

- It’s worth remembering that the Freedom of Information Act, often known as the Right to Information Act, has the potential to provoke more controversy and intense debate than almost any other part of modern government and administration. Libertarians have traditionally chanted “Freedom of Information” as a rallying cry. But, exactly, what does “Information Freedom” imply? For the most part, those who use the phrase mean that public papers, records, or information in whatever form should be easily accessible to the general public so that they can keep up with what the government is doing. In some jurisdictions, this may imply not just enabling public access to government papers in whatever form they exist, but also allowing public monitoring of government meetings, advisory bodies, and client groups. Individuals may have access to files containing personal information, with the assurance that the information will not be utilized for improper or unlawful reasons. It addresses individual access to information as well as the protection of personal information from improper usage. Is it an argument against freedom of information if individual access to such information is too expensive, too sensitive, or not worth the effort due to public apathy, or because there is little public feedback of views or ideas to inform professionals or decision-makers? Is it an argument for providing critical and pure information to bodies we trust in order for them to check the policy-making process, hold it accountable, and report on their findings?

- The concept “Information Society” was coined in order to assess the substance of the modern computerized environment. We are confronted by information repositories and retrieval systems whose capacity to store and transmit information are staggering, from financial markets to government, from national security to education, from multinational corporations to small employers, from police to social welfare, medical treatment, and social services. If we look at the constitutional history of the United Kingdom, we can see that parliament’s need to know who advised and counseled the monarch in policy development was a crucial component in the conflict between the Crown and Parliament. What is new in contemporary society is the increased knowledge of how information is used, collected, disseminated, and withheld. Our ability to collect, use, and preserve information is critical to our existence as humans. This may appear to be a lofty demand for something that cannot be stolen under English law. On a practical level, our use of knowledge prevents tragedies, and accidents, and provides sustenance. Even the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 59(I), stating, “Freedom of information is a fundamental human right and … the touchstone of all the freedoms to which the United Nations is consecrated.”

RTI & The Indian Constitution

It is necessary to emphasize at the outset that the right to information movement in India was never intended to simply provide access to public information. Rather, the goal is to establish favorable conditions for the effective exercise of the right to knowledge. It is undeniable that the Indian Constitution does not include any specific right to knowledge or even press freedom. When construed liberally, the Chapter on Fundamental Rights ensures the right to knowledge as part of freedom of speech and expression. “Corruption, nepotism, and favoritism have led to the Executive’s gross abuse of power,” writes H.M. Seervai, “which abuse has increasingly come to light partly as a result of investigative journalism and partly as a result of litigation in the Courts.” The clauses of the two constitutions (US and Indian) on freedom of speech and expression are argued to be fundamentally different. The discrepancy is reinforced by preventative detention provisions in our Constitution that do not exist in the US Constitution. Several Supreme Court judgments have been directly responsible for the development of India’s legal position on the right to information on a number of occasions. These rulings were made not in the context of the right to information, but rather in the context of the right to freedom of speech and expression. The right to freedom of speech and expression has been described as the “opposite” or “inverted” side of the right to know, and the two cannot be exercised separately.

Bennett Coleman & Co. vs. Union of India was a major case in Indian press freedom, in which the court overturned a newsprint control order, claiming that it directly harmed the Petitioners’ ability to freely publish and disseminate their newspaper. It infringed on their right to freedom of speech and expression in this way. “It is undeniable that through freedom of the press, all people have the right to speak, publish, and express their opinions,” the judges added, and “freedom of speech and expression encompasses within its compass the right of all citizens to read and be informed.” “The freedom of speech protects two sorts of interests,” Justice K.K. Mathew wrote in his dissenting opinion. There is a personal interest in achieving truth, as men need to express themselves on issues that are important to them, as well as a communal interest in achieving truth so that the country can not only accept but also follow the wisest course. The point of ultimate importance in the process of political government is no longer the words of the speakers, but the hearts of the hearers.” “The primary aim of freedom of speech and expression is that all members should be able to form their ideas and transmit them freely to others,” the court said in another decision. In summary, the underlying concept at play here is the right of the people to know.” In the following instance, it was held that if an official media or channel was made available to one party to communicate its views or criticism, the same should be made available to another opposing viewpoint. The Court ruled that a government entity with monopolistic control over a magazine could not refuse to publish any viewpoints that differed from its own. The right to transparency and freedom from arbitrariness in the criminal justice system has been developed by the courts in the realm of civil liberties. Except for clear evidence that the inmates had declined to be interviewed, the Court in Prabha Dutt vs. Union of India found that there could be no cause for the media to be denied access to interview prisoners on death row. “While there are overwhelming arguments for giving the executive the power to determine what matters may prejudice public security, those arguments give no sanction to giving the executive exclusive power to determine what matters may prejudice the public interest,” the Court said in State of U.P. v. Raj Narain. There are few subjects of public interest that cannot be safely discussed in public once national security considerations are removed.” “In a system of responsibility like ours, where all public servants must be accountable for their actions, there can be few secrets,” Justice K.K.Mathew continued. Every public act, everything that is done in a public fashion by their public functionaries, has a right to be known by the people of this country. They have a right to know the specifics of every public transaction in all of its ramifications. When claiming confidentiality for public actions that do not jeopardize public security, one must be mindful of the people’s right to know. Covering regular activity with a shroud of secrecy is not in the public interest. Such anonymity is rarely desired legitimately. It is commonly sought for the sake of political parties, personal gain, or bureaucratic routine. The primary safeguard against oppression and corruption is authorities’ responsibility to explain or defend their actions.”

RTI Act, 2005

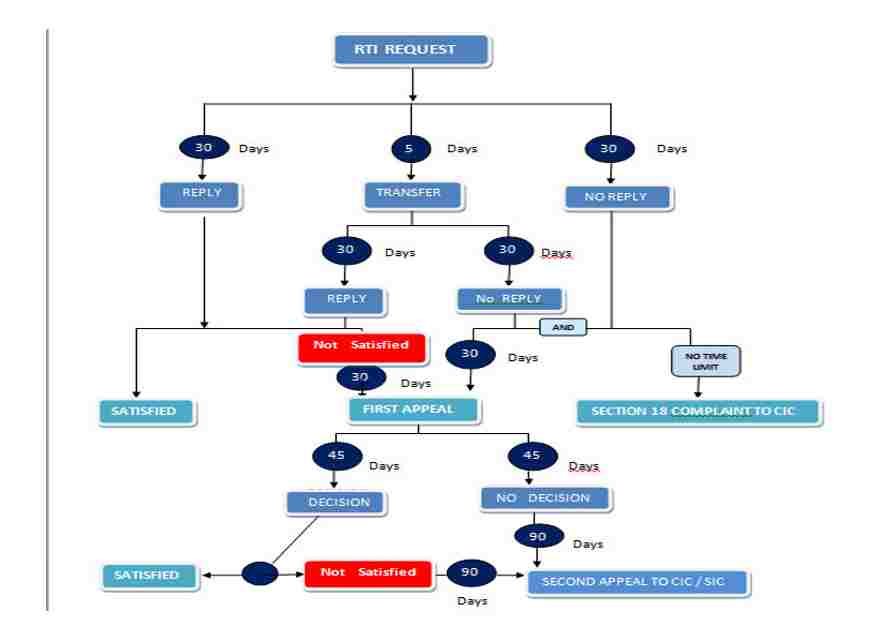

Parliament passed the “Right to Information Bill, 2004” on June 15, 2005, repealing the Freedom of Information Act, 2002. “The Right to Information Act” was notified in the Gazette of India on June 21, 2005, after repealing the Freedom of Information Act, 2002. Since October 12, 2005, the “Right to Information Act” has been fully active, allowing citizens of India to have secure access to information under the control of public authorities. This law responds to a long-standing demand of the people expressed through various popular movements, and gives substance and meaning to the right to information, which has been recognized by the Supreme Court since 1973 as a corollary of the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1). (a). It was enacted to lay down the practical framework for people’s right to information. Except for Jammu & Kashmir, which is covered by a state-level law, the Act applies to all Indian states and union territories. The RTI Act is unique in that it transfers the burden of proof from the appellant to the respondent. India, like the United States, enacted FOIA-style legislation. The RTIA, on the other hand, has a broader scope. While the FOIA only pertains to the federal government in the United States, the RTIA covers all state and local governments in India. Any citizen may request information from a “public authority” under the Act’s requirements, which must respond promptly or within thirty days, making the government and its employees more accountable and responsible.

Unlike many other countries (such as the United Kingdom), India required only a few months to put the Act into effect once it was enacted. This amount of time was insufficient to alter government mindsets, build infrastructure, develop new processes, and build the capacity to supply information under this Act. As a result, there are implementation challenges that must be identified and solved.

Despite being a long-established federal democracy, India faces economic and political issues that the affluent and industrialized countries that originally implemented FOIA-style laws did not. Despite the enormous urbanization that has occurred across the country in recent decades, almost two-thirds of India’s total population still lives in rural areas. Despite the fact that India’s literacy rate increased to 68 percent in 2007 from 12 percent at the end of British control in 1947, a person is considered literate if he can read and write in any language. Mismanagement and widespread corruption can impair government projects aimed at promoting social and economic growth.

Issues In Implementation Of RTI ACT

According to the RAAG report, over two million requests for information were filed under the RTI by Indian individuals in the first two and a half years of its implementation, from October 2005 to March 2008. Sections 27(1) and 28(1) of the RTI Act direct the appropriate governments and competent authorities to create rules for the Act’s implementation. PIOs are obligated to provide appropriate assistance to applicants in the writing and submission of RTI applications under Section 6 of the RTI Act. However, the implementation of these clauses appears to fall far short of expectations. It will continue to be an issue unless the many challenges associated with the implementation of the RTI Act are properly addressed by the appropriate Government and Public Authority in tandem.

The following challenges linked to RTI Act implementation can be shown, point by point, by looking at the studies done by RAAG and PWC:

Low Degree of Awareness: Section 26 of the Act specifies that the appropriate government may establish and organize educational programs to improve the public’s understanding of how to exercise the rights recognized by the Act, particularly among disadvantaged communities. However, the government has yet to develop a formal instructional campaign to increase public understanding of the RTI Act among Indian citizens.

Quality of Awareness: It is crucial to note that RTI awareness among the general public is extremely poor, particularly among disadvantaged groups such as women, the rural population, and individuals who fall within the OBC/SC/ST category.

Non-availability of RTI Implementation User Guides for Information Seekers: Under Section 26 of the RTI Act, the appropriate government is required to create and disseminate user guides for information seekers (within eighteen months of the Act’s passage). However, in the majority of states, the Nodal Departments have yet to publish these manuals. The Executive Branch of the Government

Standard RTI Application Forms: While the Act does not require the use of a standard application form, certain states have done so under Section 26(3) (c) of the Act. The standard form aids in gathering basic information such as addresses and phone numbers, as well as the form in which it is asked. The Public Authority can then use this information to determine the nature of frequent information requests, which can then be granted as a suo-moto disclosure under Section 4(2) of the Act. Only a few states have specified a standard form thus far.

Inconvenient RTI Application Submission Channels: A citizen can make a request “in writing or through electronic means in English or Hindi or in the official language of the area in which the application is being made…” according to Section 6(1) of the Act. However, insufficient attempts have been made to receive RTI petitions via electronic means, such as email/website, which the appropriate government can accomplish utilizing Section 26. (3c). There is no method to obtain information from any government website, and there is no means to pay the required fees for such information online. It means that five years later, online information is still unavailable.

Objectives Of RTI

To provide citizens with a legal framework for accessing information.

To encourage public authorities to be more accountable, hence reducing corruption.

To reconcile competing interests and prioritize government operations and resource allocation.

To keep democracy’s values alive.

Conclusion

It’s too soon to tell if RTIA will be a “big and revolutionary act.” How the RTIA is implemented will determine if it fulfills the dreams of the Indian people. It is impossible to say whether India is finally on the cusp of passing a groundbreaking law that would clearly guarantee the right to information to the people. The fast passage of FOIA-style laws in many industrialized and developing countries has exacerbated implementation issues. However, India’s execution has been scrutinized more thoroughly and obstinately than any other country. According to reports, when civil society organizations and ordinary citizens began to use the RTI Act, corruption and mismanagement have decreased, and government responsiveness has improved. Provisions in the legislation encouraging “Proactive Disclosure” of critical information are frequently ignored. It has been observed that as a result of public officials’ non-compliance, the number of complaints has steadily increased, causing the commissions charged with enforcing the legislation to struggle.

If these issues are not sufficiently addressed, the law will be designed to benefit just those who are wealthy and have the expertise and resources to have the law enforced in their favor. The same thing has happened in many other countries, where a law enacted to meet and serve progressive goals for the public good eventually supports the interests of those who are already well-off by bolstering their position. In India, like in other countries, proponents of the Right to Information Act have been constantly confronted with attempts by ministers and bureaucrats to change the Act in order to limit the right to information.

Due to traditions and British colonial domination, India’s bureaucratic customs and administrative practices have developed over the decades. Indeed, India continues to struggle with its administrative structure to some extent. India’s Right to Information Act is a good example of FOIA-style legislation in practice. This is due to primarily two factors: the enormous population of the country that will benefit from the law, and the far more challenging circumstances under which the law will be implemented in comparison to other nations that have already done so. Numerous obstacles remain to be overcome, and the passage of a FOIA-style law is only the first step on the long road to transparency. This will not be achievable until the country’s judiciary, particularly the higher judiciary, accepts responsibility for the people’s right to knowledge. Because in the end, it will be the greatest way for the court to keep the faith and trust of the country’s ordinary men.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About RTI And RTIA

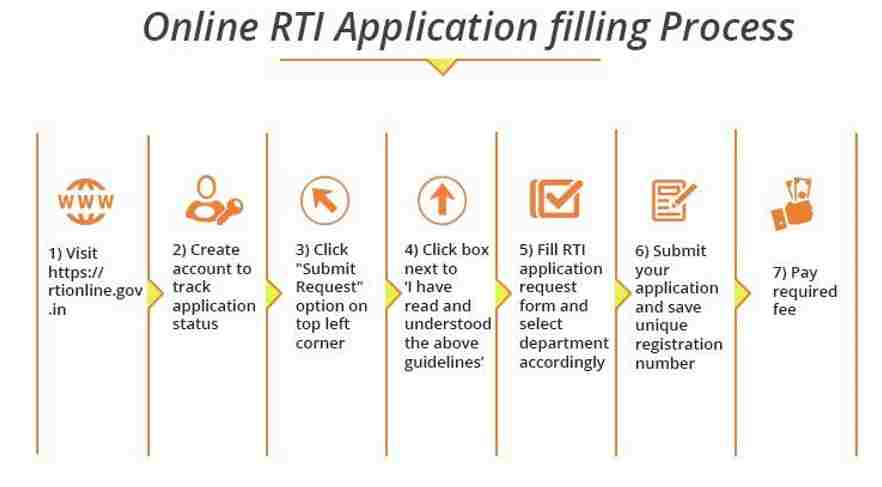

1. There are simply three steps to filing an RTI Application.

- Step 1: Writing an application specified with all the particulars of information.

- Step 2: Submission of evidence of payment of application fee.

- Step 3: Sending the application to the concerned Assistant Public Information/ Public Information Officer.

2. An average of 4,800 RTI applications are filed every day in various government departments every day.

3. Since the Act’s inception, at least 65 RTI advocates are known to have been slain. In addition, 400 activists are said to have been harassed.

4. The RTI is primarily used by men (90 percent) from metropolitan regions, with only 14 percent of total RTI applicants being from rural areas.

5. In 2016, the Ministry of Finance received a total of 1.55 lakh RTI requests. With 1.11 lakh applications received, the I&B Ministry came in second.

6. The RTI Act was passed by the Parliament of India that applies to all States and Union Territories of India including Jammu & Kashmir after the abrogation of Article 370 from the Indian Constitution.

7. Parliament passed this law on June 15, 2005, and it went into effect on October 13, 2005. The Official Secrets Act of 1923, as well as numerous other specific legislation, imposed restrictions on information disclosure in India, which the new RTI Act removes.

8. Any citizen may request information from a “public authority” (a government body) under the Act’s requirements, which must respond promptly or within thirty days.

9. To obtain information through an RTI application, one must pay an application fee. It is Rs.10 for Union Government departments.

10. You must pay additionally Rs.2 per page of information provided for Central Government Departments in order to obtain it. Various states, however, charge different fees.

11. Every public entity is also required by the Act to computerize its records for wide dissemination and to disclose specific types of information to individuals with the least amount of formal requests for information.

12. The rate of disposal of appeals filed in connection with RTI applications has also gone up over the years. In 2011-12, 23,112 appeals out of 33,922 filed were disposed of. In 2015-16, 1, 06,556 appeals out of a total 1, of 10,034 were disposed of.

13. Right to Information along with being a statutory right is also a fundamental right under Article 21 (Residuary Rights) of the Indian Constitution.