Introduction

- The Indian Independence movement is a series of historical events which lasts from 1857 to 1947. The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian Independence began from Bengal. It later took root in the newly formed Indian National Congress with prominent moderate leaders seeking the right to appear for Indian Civil Service examinations in British India, as well as more rights (economical in nature) for the people of the soil. The early part of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards political self-rule proposed by leaders such as the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate, Aurobindo Ghosh, and V. O. Chidambaram Pillai.

- The last stages of the self-rule struggle from the 1920s were characterized by Congress’s adoption of Mahatma Gandhi’s policy of non-violence and civil disobedience and several other campaigns. B. R. Ambedkar championed the cause of the “disadvantaged” sections of Indian society.

The Indian independence movement encompassed all sections of society. It was in constant ideological evolution. Although the underlying ideology was anti-colonial, it was supported by a vision of independent, economic development coupled with a secular, democratic, republican, and civil-libertarian political structure. After the 1930s, the movement took on a strong socialist orientation. The work of these various movements ultimately led to the Indian Independence Act 1947, which ended suzerainty in India, and created Pakistan.

India remained a Crown Dominion until 26 January 1950, when the Constitution of India came into force, establishing the Republic of India; Pakistan was a dominion until 1956 when it adopted its first republican constitution. In 1971, East Pakistan declared independence as the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Background

1. Early British Colonialism In India

- The first European to reach India was the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama who reached Calicut in 1498 in search of spice. The decline of the Mughal Empire in the first half of the eighteenth century provided the British with the opportunity to establish a firm foothold in Indian politics. After the Battle of Plassey, during which the East India Company’s Indian Army under Robert Clive defeated Siraj ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, the Company established itself as a major player in Indian affairs and soon afterward gained administrative rights over the regions of Bengal, Bihar and Midnapur part of Odisha, following the Battle of Buxar in 1764.

Mir Jafar’s betrayal towards the Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah of Bengal in Plassey made the battle one of the main factors of British supremacy in the sub-continent.

After the defeat of Tipu Sultan, most of South India came either under the Company’s direct rule, or under its indirect political control as part of a princely state in a subsidiary alliance. The Company subsequently seized control of regions ruled by the Maratha Empire, after defeating them in a series of wars. Punjab was annexed in 1849, after the defeat of the Sikh armies in the First (1845–1846) and Second (1848–49) Anglo-Sikh Wars.

- After the defeat of Tipu Sultan of Mysore, most of South India was now either under the company’s direct rule or under its indirect political control.

2. Early Rebellions

Maveeran Alagumuthu Kone (1710–1757), from Kattalankulam in Thoothukudi District, was an early chieftain and rebel against the British presence in Tamil Nadu. Born into a Konar Yadava family, he became a military leader in the town of Ettayapuram and was defeated in battle against the British and Maruthanayagam’s forces in 1757. His prominent exploits were his confrontations with Marudhanayagam, who later rebelled against the British in the late 1750s and early 1760s. Nelkatumseval in the present Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu was his headquarters.

One of the earliest of these on record was led by Binsu Manki around 1771 near Bundu in Ranchi district due to discontent over transfer of Jharkhand to East India Company. The Rangpur Dhing took place from 1782-1783 in nearby Rangpur, Bengal. Following the Binsu Manki’s revolt in Jharkhand, numerous rebellions across the region took place including the Bhumij Revolt of Manbhum from 1798–99; the Chero Uprising of Palamu in 1800 under the leadership of Bhukan Singh, and two uprising of the Munda community in Tamar region, during 1807 lead by Dukan Mank, and 1819-20 under the leadership Bundu and Konta. The Ho Rebellion took place when the Ho community first came in contact with the British, from 1820-21 near Chaibasa on the Roro River in West Singhbhum, but were defeated by the technologically enhanced colonial cavalry. A larger Bhumij Revolt occurred near Midnapur in Bengal, under the leadership of Ganga Narain Singh who had previously also been involved in co-leading the Chuar Rebellions in these regions from 1771-1809.

The Santhal Hul was a large impactful movement of over 60,000 Santhals that happened from 1855-57 (but started as early as 1784) and was particularly lead by siblings – brothers Sidhu, Kanhu, Chand and Bhairav and their sisters Phulo and Jhano from the Murmu clan in its most fervent years that lead up to the Revolt of 1857. Birsa Munda belonged to the Munda community and lead thousands of people from Munda, Oraon, and Kharia communities in “Ulgulaan” (revolt) against British political expansion and those who advanced it, against forceful conversions of Indigenous peoples into Christianity (even creating a Birsaite movement), and against the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their lands. They brutally attacked the Dombari Hills where Birsa had repaired and water tank and made his revolutionary headquarters between January 7–9, 1900, murdering minimum 400 of Munda warriors who had congregated there, akin to the attacks on the people at Jallianwallah Bagh, however, receiving much less attention. Birsa was ultimately captured in the Jamkopai forest in Singhbhum, and assassinated by British in jail in 1900, with rushed cremation/burial conducted to ensure his movement was subdued.

In September 1804 the King of Khordha, Kalinga was deprived of the traditional rights of Jagannath Temple which was a serious shock to the King and the people of Odisha. Consequently, in October 1804 a group of armed Paiks attacked the British at Pipili. This event alarmed the British force. Jayee Rajguru, the chief of the Army of Kalinga, requested all the kings of the state to join hands for a common cause against the British. Rajguru was killed on 6 December 1806. After Rajguru’s death, Bakshi Jagabandhu commanded an armed rebellion against the East India Company’s rule in Odisha which is known as Paik Rebellion, the first Rebellion against the British East Indian Company.

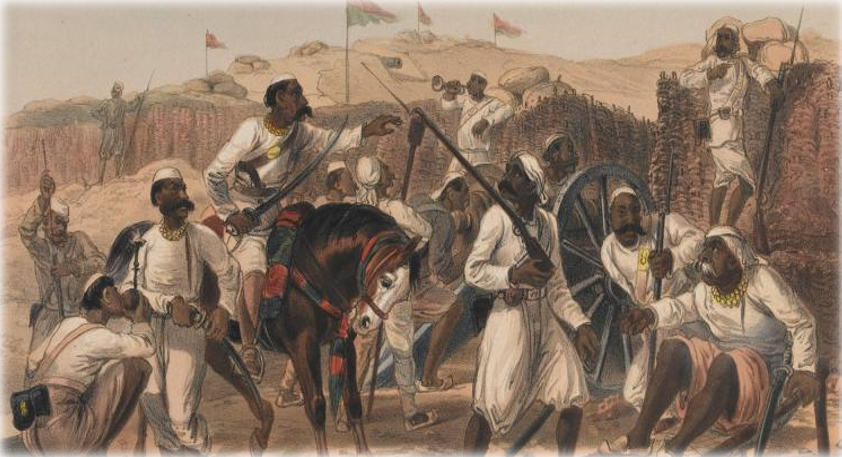

3. Rebellion Of 1857

- The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a large-scale rebellion in northern and central India against the British East India Company’s rule. It was suppressed and the British government took control of the company. The conditions of service in the company’s army and cantonments increasingly came into conflict with the religious beliefs and prejudices of the sepoys. The predominance of members from the upper castes in the army, perceived loss of caste due to overseas travel, and rumors of secret designs of the government to convert them to Christianity led to the deep discontent among the sepoys. The sepoys were also disillusioned by their low salaries and the racial discrimination practiced by British officers in matters of promotion and privileges. The Marquess of Dalhousie’s policy of annexation, the doctrine of lapse (or escheat) applied by the British, and the projected removal of the descendants of the Mughals from their ancestral palace at Red Fort to the Qutub Minar complex (near Delhi) also angered some people.

Rise Of Organized Movements

The decades following the Rebellion were a period of growing political awareness, the manifestation of Indian public opinion and the emergence of Indian leadership at both national and provincial levels. Dadabhai Naoroji formed the East India Association in 1867 and Surendranath Banerjee founded the Indian National Association in 1876. However, this period of history is still crucial because it represented the first political mobilization of Indians, coming from all parts of the subcontinent and the first articulation of the idea of India as one nation, rather than a collection of independent princely states.

Religious groups played a role in reforming Indian society. These were of several religions from Hindu groups such as the Arya Samaj, the Brahmo Samaj, to other religions. The work of men like Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna, Sri Aurobindo, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Subramanya Bharathy, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Rabindranath Tagore and Dadabhai Naoroji, as well as women such as the Scots–Irish Sister Nivedita, spread the passion for rejuvenation and freedom. The rediscovery of India’s indigenous history by several European and Indian scholars also fed into the rise of nationalism among Indians.

- The triumvirate also is known as Lal Bal Pal (Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai), along with V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Sri Aurobindo, Surendranath Banerjee, and Rabindranath Tagore were some of the prominent leaders of movements in the early 20th century. The Swadeshi movement was the most successful.

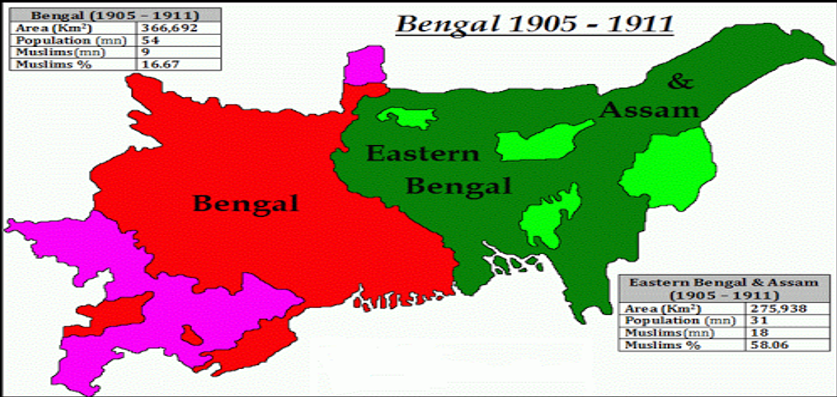

After Lord Curzon announced the partition of Bengal in 1905, there was massive opposition from the people of Bengal. Initially, the partition plan was opposed through press campaign. The total follower of such techniques led to the boycott of British goods and the people of India pledged to use only swadeshi or Indian goods and to wear only Indian cloth.

According to Surendranath Banerji, the Swadeshi movement changed the entire texture of our social and domestic life. The songs composed by Rabindranath Tagore, Rajanikanta Sen and Syed Abu Mohd became the moving spirit for the nationalists. The movement soon spread to the rest of the country and the partition of Bengal had to be firmly inhaled on the first of April, 1912.

Rise Of Indian Nationalism

By 1900, although the Congress had emerged as an all-India political organization, it did not have the support of most Indian Muslims. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan launched a movement for Muslim regeneration that culminated in the founding in 1875 of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (renamed Aligarh Muslim University in 1920). Its objective was to educate students by emphasizing the compatibility of Islam with modern western knowledge. The diversity among India’s Muslims, however, made it impossible to bring about uniform cultural and intellectual regeneration.

Congressmen saw themselves as loyalists, but wanted an active role in governing their own country, albeit as part of the Empire. This trend was personified by Dadabhai Naoroji, who went as far as contesting, successfully, an election to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, becoming its first Indian member.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was the first Indian nationalist to embrace Swaraj as the destiny of the nation. Tilak deeply opposed a British education system that ignored and defamed India’s culture, history, and values. He resented the denial of freedom of expression for nationalists and the lack of any voice or role for ordinary Indians in the affairs of their nation. For these reasons, he considered Swaraj as the natural and only solution. His popular sentence “Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it” became the source of inspiration for Indians.

In colonial India, the All India Conference of Indian Christians (AICIC), which was founded in 1914, played an important role in the Indian independence movement, advocating for swaraj and opposing the partition of India. The AICIC also was opposed to separate electorates for Christians, believing that the faithful “should participate as common citizens in one common, the national political system”. The All India Conference of Indian Christians and the All India Catholic Union formed a working committee with M. Rahnasamy of Andhra University serving as President and B.L. Rallia Ram of Lahore serving as General Secretary; in its meeting on 16 April 1947 and 17 April 1947, the joint committee prepared a 13 point memorandum that was sent to the Constituent Assembly of India, which asked for religious freedom for both organizations and individuals; this came to be reflected in the Constitution of India.

Partition Of Bengal, 1905

In July 1905, Lord Curzon, the Viceroy and Governor-General (1899–1905), ordered the partition of the province of Bengal. The stated aim was to improve administration. However, this was seen as an attempt to quench nationalistic sentiment through divide and rule. The Bengali Hindu intelligentsia exerted considerable influence on local and national politics. The partition outraged Bengalis. Widespread agitation ensued in the streets and in the press, and the Congress advocated boycotting British products under the banner of swadeshi, or indigenous industries. A growing movement emerged, focusing on indigenous Indian industries, finance, and education, which saw the founding of the National Council of Education, the birth of Indian financial institutions and banks, as well as an interest in Indian culture and achievements in science and literature. Hindus showed unity by tying Rakhi on each other’s wrists and observing Arandhan (not cooking any food). During this time, Bengali Hindu nationalists like Sri Aurobindo, Bhupendranath Datta, and Bipin Chandra Pal began writing virulent newspaper articles challenging the legitimacy of British rule in India in publications such as Jugantar and Sandhya and were charged with sedition.

The Partition also precipitated increasing activity from the then still nascent militant nationalist revolutionary movement, which was particularly gaining strength in Bengal and Maharashtra from the last decade of the 1800s. In Bengal, Anushilan Samiti, led by brothers Aurobindo and Barin Ghosh organized a number of attacks on figureheads of the Raj, culminating in the attempt on the life of a British judge in Muzaffarpur. This precipitated the Alipore bomb case, whilst a number of revolutionaries were killed, or captured and put on trial. Revolutionaries like Khudiram Bose, Prafulla Chaki, Kanailal Dutt who were either killed or hanged became household names.

1. Jugantar

Jugantar was a paramilitary organization. Lead by Barindra Ghosh, 21 revolutionaries, including Bagha Jatin, started to collect arms and explosives and manufactured bombs.

One of them, Hemchandra Kanungo obtained his training in Paris. After returning to Kolkata he set up a combined religious school and bomb factory at a garden house in the Maniktala suburb of Calcutta. However, the attempted murder of district Judge Kingsford of Muzaffarpur by Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki (30 April 1908) initiated a police investigation that led to the arrest of many of the revolutionaries.

2. Alipore Bomb Conspiracy Case

- Several leaders of the Jugantar party including Aurobindo Ghosh were arrested in connection with bomb-making activities in Kolkata. Several of the activists were deported to the Andaman Cellular Jail.

3. Delhi-Lahore Conspiracy Case

- The Delhi-Lahore Conspiracy, hatched in 1912, planned to assassinate the then Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, on the occasion of transferring the capital of British India from Calcutta to New Delhi. Involving revolutionary underground in Bengal and headed by Rash Behari Bose along with Sachin Sanyal, the conspiracy culminated on the attempted assassination on 23 December 1912 when a homemade bomb was thrown into the Viceroys’s Howdah when the ceremonial procession moved through the Chandni Chowk suburb of Delhi. The Viceroy escaped with his injuries, along with Lady Hardinge, although Mahout was killed.

4. Howrah Gang Case

- Most of the eminent Jugantar leaders including Bagha Jatin alias Jatindra Nath Mukherjee who were not arrested earlier were arrested in 1910, in connection with the murder of Shamsul Alam. Thanks to Bagha Jatin’s new policy of a decentralized federated action, most of the accused were released in 1911.

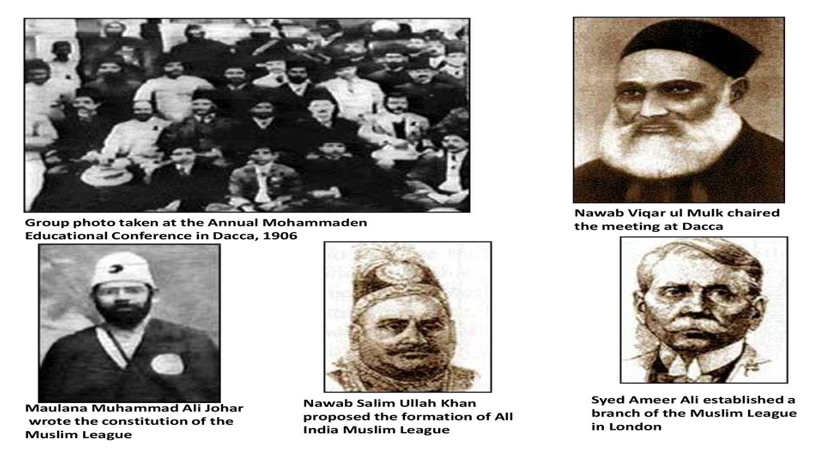

All India Muslim League

- The All-India Muslim League was founded by the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference at Decca (now in Dhaka, Bangladesh), in 1906. In 1916, Muhammad Ali Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress, which was the largest Indian political organization. Like most of the Congress at the time, Jinnah did not favor outright self-rule, considering British influences on education, law, culture, and industry as beneficial to India. Jinnah became a member of the sixty-member Imperial Legislative Council. The council had no real power or authority and included a large number of unelected pro-Raj loyalists and Europeans. Nevertheless, Jinnah was instrumental in the passing of the Child Marriages Restraint Act, the legitimization of the Muslim waqf (religious endowments), and was appointed to the Sandhurst committee, which helped establish the Indian Military Academy at Dehradun.

Purna Swaraj

- The conference appointed a drafting committee under Motilal Nehru to draw up a constitution for India. The Kolkata session of the Indian National Congress asked the British government to accord dominion status to India by December 1929, or a countrywide civil disobedience movement would be launched. In the midst of rising political discontent and increasingly violent regional movements, the call for complete sovereignty and an end to British rule began to find increasing grounds for credence with the people. Under the presidency of Jawaharlal at his historic Lahore session in December 1929, the Indian National Congress adopted the objective of complete self-rule. It authorized the Working Committee to launch a civil disobedience movement throughout the country. It was decided that 26 January 1930 should be observed all over India as the Purna Swaraj (complete self-rule) Day.

In March 1931, the Gandhi–Irwin Pact was signed, and the government agreed to set all political prisoners free (although, some of the great revolutionaries were not set free and the death sentence for Bhagat Singh and his two comrades was not taken back which further intensified the agitation against Congress not only outside it also from within). For the next few years, Congress and the government were locked in both conflict and negotiations until what became the Government of India Act 1935 could be hammered out.

The Civil Disobedience Movement indicated a new part in the process of the Indian self-rule struggle. It did not succeed by itself, but it brought the Indian population together, under the Indian National Congress’s leadership. The movement allowed the Indian independence community to revive their inner confidence and strength against the British Government. Overall, the civil disobedience Movement was an essential achievement in the history of Indian self-rule because it persuaded New Delhi of the role of the masses in self-determination.

Struggle For Independence

- The day of 15th August in 1947 has been embossed in the golden history of India. It is the day when India got its freedom from the 200 years of British rule. It was a hard and long high-stakes struggle in which many freedom fighters and great men sacrificed their lives for our beloved motherland. India commends its Independence Day on 15th August. Autonomy day helps us remember every one of the penances our political dissidents made to make India liberated from British rule. On fifteenth August 1947, India was announced free from British imperialism and turned into the biggest vote-based system on the planet. Independence Day is like the birthday of our country. We celebrate 15th August every year as our Independence Day. It is celebrated as a national holiday throughout the country. It is called the red-letter day in the history of our country.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About Indian Independence Movement

Our current national flag had a number of iterations. The version you know today was made by Pingali Venkayya at Bezwada in 1921.

Mahatma Gandhi could not celebrate the first Independence Day in Delhi.

Only Khadi Development and village industries have the license to produce or supply our national flag.

We did not have a national anthem on our first Independence Day.

Lord Mountbatten was forced to attend the Independence Day of both India and Pakistan, which is why he brought forward Pakistan’s Independence Day to 14th August.

South Korea, the Republic of Congo, and Liechtenstein share their Independence Day with India.

Hindi is not the national language of India. It was chosen as India’s first official language and was declared so in 1949.

The border between India and Pakistan was drawn by British lawyer Sir Cyril Radcliffe.

Our first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was a style icon. He featured in an issue of Vogue Magazine.

Goa was a Portuguese state when India became independent. It became a part of the Indian union in 1961.

Lord Mountbatten chose 15th August as India’s Independence Day because it honored the second anniversary of Japan’s surrender to the Allied forces.

Goa was a Portuguese state when India became independent. It became a part of the Indian union in 1961.

After Independence, 560 princely states became a part of the Indian union.