- Indian classical dance is a shelter home for all those who do not find joy in the monotony of life. It is a deep-rooted practice of body and mind that enables one to think and live with the most pride. It is also an umbrella terminology for various performance arts associated with musical theatre styles actually holding consonance to the famous Sanskrit text, Natyashastra. The number of classical dances ranges from eight to more, depending on the variety of sources and learnt individuals. Presently, the Sangeet Natak Academy recognizes eight, namely Bharatnatyam, Kathak, Kuchipudi, Odissi, Kathakali, Sattriya, Manipuri and Mohiniyattam. Scholars such as Drid Williams added Chhau, Yakshagana and Bhagavata Mela to the list breaking the thin line between folk and classical dance forms. Additionally, the Indian Ministry of Culture includes Chhau in its classical list. These dances are both traditional and regional in flavor and preach. They consist of compositions in a plethora of languages like Telugu, Tamil, Sanskrit, Kannada, Hindi, or any other Indian language. They represent a unity of core ideas in a diversity of styles, costumes and expression. At present officially there are 9 classical dances in India.

Types Of Classical Dance

The Natyasashtra, an ancient text, is the foundational stone for classical dances in India. It has been attributed to the ancient Sanskrit scholar Bharata Muni. First complete compilation dating back to 200 BCE to 200 CE, variably. The most studied version of the Natyashastra consists of about 6000 verses structured into 36 chapters. The text, states Natalia Lidova, describes the theory of Tāṇḍava dance (Shiva), the theory of raBaavangal, bhāva, expression, gestures, acting techniques, basic steps, standing postures – all of which are part of Indian classical dances. Dance and performance arts, states this ancient text, are a form of expression of spiritual ideas, virtues, and the essence of scriptures. Lord Nataraja, an incarnation of Shiva is therefore considered as the God of dance according to Hindu mythological believers.

Indian classical dances are traditionally performed as an expressive drama-dance form of religious performance art, related to Vaishnavam, Saivam. Epic and folk-like entertainment that includes story-telling from Tamil or other Dravidian language plays. This is true mostly for the Southern peninsular Dance forms like Bharatnatyam, Kuchipudi, Mohiniattam, and Kathakali. Kathak, which is from northern India, mainly uses compositions in Sanskrit or Hindi and its related languages.

Odissi, Manipuri, and Sattiya use the languages of the regions they belong to as well as Sanskrit or Hindi. As religious art, they are either performed inside the sanctum of a temple or nearby to it. Folksy entertainment may also be performed in temple grounds or any fairground, typically in a rural setting by traveling troupes of artists; alternatively, they have been performed inside the halls of royal courts or public squares during festivals.

Realisation

Dance has been more than just a leisure activity for dancers. It has greater implications for a dancer, sometimes inseparable from their identity. Classical dance is a unique set of art forms that comes with a realization to all practitioners and followers, often called rasika’s. The realization of self through performing art is not only a divine interpretation of God’s word but also an act of nature. It is however very difficult to differentiate between dance and dancer’s realizations after the long and hard training periods. It shapes a dancer into an incarnation of a selfless idol of patience, perseverance, discipline, dedication, and hard work. The classical dance forms recognized by the Sangeet Natak Akademi and the Ministry of Culture are: Bharatanatyam from Tamil Nadu, Kathak from Uttar Pradesh, Kathakali from Kerala, Kuchipudi from Andhra Pradesh, Odissi from Odisha, Sattriya, from Assam, Manipuri from Manipur, and Mohiniyattam from Kerala.

Renowned dancers of Indian classical dance forms.

There have been many famous dancers in each Indian classical dance form. Some of them include;

Bharatanatyam – Rukmini Devi, Padma Subrahmanyam, Vyjayanthimala, Sheema Kermani, Hema Malini, etc.

Kathak – BirjuMaharaj, Nahid Siddiqui, Sambhu Maharaj, Lacchu Maharaj, Gopi Krishna, Saswati Sen, etc.

Kathakali – Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair, Ramanakutty Nair, etc.

Kuchipudi – Mallika Sarabhai, V. SatyanarayanaSarma, DeepaShashindran, etc.

Odissi – Sujata Mohapatra, MadhaviMudgal, Kelucharan Mohapatra, SurendraNath Jena, Shobana Sahajananan

Mohiniyattam – Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, Shobhana, Sunanda Nair, Kalamandalam Radhika, Thankamani, Kalamandalam Hymavathy

Art Behind Dance

All major classical Indian dance forms include in the repertoire, three categories of performance in the Natya Shastra. These are Nritta, Nritya and Natya. The Nritta performance is an abstract, fast and rhythmic aspect of the dance. The viewer is presented with pure movement, wherein the emphasis is on beauty in motion, form, speed, range and pattern. This part of the repertoire has no interpretative aspect, no telling of the story. It is a technical performance and aims to engage the senses (Prakriti) of the audience.

The Nritya is a slower and more expressive aspect of the dance that attempts to communicate feelings, storyline particularly with spiritual themes in Hindu dance traditions. In a Nritya, the dance-acting expands to include silent expression of words through gestures and body motion set to musical notes. The actor articulates a legend or a spiritual message. This part of the repertoire is more than sensory enjoyment. It aims to engage the emotions and mind of the viewer.

The Natyam is a play, typically a team performance, but can be acted out by a solo performer where the dancer uses certain standardized body movements to indicate a new character in the underlying story. A Natya incorporates the elements of a Nritya.

All classical dances of India used similar symbolism and rules of gestures in abhinaya (acting). The roots of abhinaya are found in the Natyashastra text which defines drama in verse 6.10 as that which aesthetically arouses joy in the spectator, through the medium of the actor’s art of communication, which helps connect and transport the individual into a super sensual inner state of being. A performance art, asserts Natyashastra, connects the artists and the audience through abhinaya (literally, “carrying to the spectators”), that is applying body-speech-mind and scene, wherein the actors communicate to the audience, through song and music.

Drama in this ancient Sanskrit text is an art to engage every aspect of life, to glorify and gift a state of joyful consciousness.

The communication through symbols is in the form of expressive gestures (mudras or hastas) and pantomime set to music. The gestures and facial expressions convey the ras (sentiment, emotional taste) and bhava (mood) of the underlying story. In Hindu classical dances, the artist successfully expresses the spiritual ideas by paying attention to four aspects of a performance:

Angika (gestures and body language), Vachika (song, recitation, music, and rhythm), Acharya (stage setting, costume, makeup, jewelry), Sattvika (artist’s mental disposition and emotional connection with the story and audience, wherein the artist’s inner and outer state resonates). Abhinaya draws out the bhava (mood, psychological states).

Types

1. Bharatnatyam

Bharatanatyam is a pre-eminent Indian classical dance form presumed to be the oldest classical dance heritage of India. It is regarded as the mother of many other Indian classical dance forms. Conventionally a solo dance performed only by women, it initiated in the Hindu temples of Tamil Nadu and eventually flourished in South India. The theoretical base of this form traces back to ‘Natya Shastra’ and form of illustrative anecdote of Hindu religious themes and spiritual ideas are emoted by dancers with precise footwork and adorable gestures. The performance repertoire includes nrita, nritya and natya. The performer is accompanied by a singer, musicians, and particularly the guru, who directs and conducts the performance.

The name of this famous dance form was derived by joining two words, ‘Bharata’ and Natyam’ where ‘Natyam in Sanskrit means dance and ‘Bharata’ is a mnemonic comprising ‘bha’, ‘ra’ and ‘ta’ which respectively means ‘bhava’ that is emotion and feelings; ‘raga’ that is a melody; and ‘tala’ that is rhythm. According to legends Lord Brahma revealed Bharatanatyam to the sage Bharata who then encoded this holy dance form in Natya Shastra.

Tamil literature also greatly references this dance form. Earlier between 300 BCE to 300 CE Devadasis, dedicated servants to Lord performed the dance form. Soon the devadasi culture became an integral part of rituals in South Indian temples. In the 18th century, with the emergence of the East India Company British colonies were set up leading to the marked decline of various classical dance forms which were subjected to contemptuous fun and discouragement including Bharatanatyam. With the finding of the ‘Madras Music Academy’ Bharatanatyam choreographer Rukmini Devi Arundale, Bharatanatyam was revived. Eminent Bharatanatyam dancers like Arundale and Balasaraswati expanded the dance form out of Hindu temples and established it as a mainstream dance form. Today this ancient classical dance form also includes technical performances as also non-religious and fusion-based themes.

The dance form typically comprises certain sections performed in sequence namely Alarippu, Jatiswaram, Shabdam, Varnam, Padam, and Thillana. The style of dressing of a Bharatanatyam dancer is more or less similar to that of a Tamil Hindu bride wearing a gorgeous tailor-made sari with pleats and traditional jewelry that adorn her face with vivid face make-up. The Bharatnatyam dancer is accompanied by a nattuvanar that is a vocalist who generally conducts the whole performance. Carnatic style and instruments are played in a Bharatnatyam performance. The verses recited during the performance are in Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada, and Telugu.

- The four Nattuvanars namely Ponaiyah, Vadivelu, Sivanandam, and Chinnaiya who are renowned as TanjaoreBandhu and who thrived in the Durbar of Maratha ruler, Sarfoji-II from 1798 to 1832 shaped up the modern-day Bharatanatyam. Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, a dance guru from the village of Pandanallur was a noted exponent of Bharatanatyam who is predominantly known for his style referred to as the Pandanallur school of Bharatanatyam. One of his students Rukmini Devi championed and performed the Pandanallur (Kalakshetra) style and also remained one of the leading proponents of the classical dance revival movement. Balasarswati who was regarded as a child prodigy by Vidhwans and Pandits also joined hands in reviving the dance form. Imminent Bharatanatyam artists include Mrinalini Sarabhai, her daughter Mallika Sarabhai, Padma Subramanyam, AlarmelValli, Yamini Krishnamurthy and Anita Ratnam among others.

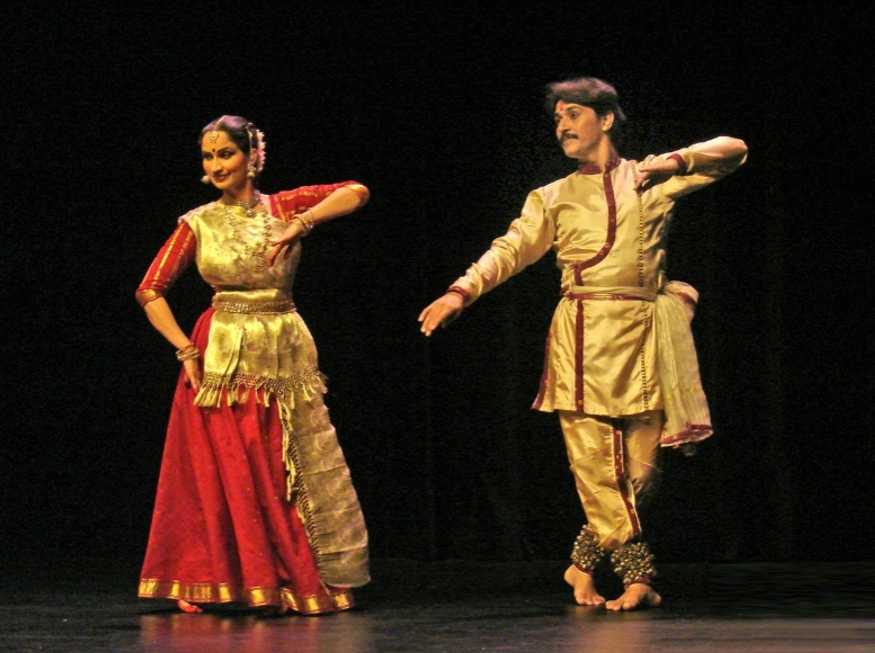

2. Kathak

Kathak is one of the main genres of ancient Indian classical dance and is traditionally regarded to have originated from the traveling bards of North India referred to as Kathakars or storytellers. The Kathakars communicate stories through rhythmic foot movements, hand gestures, facial expressions, and eye work. This performing art that incorporates legends from ancient mythology and great Indian epics, especially from the life of Lord Krishna became quite popular in the courts of North Indian kingdoms. Three specific forms of this genre which are three Gharanas (schools), which mostly differ in the emphasis given to footwork versus acting, are more famous names, the Jaipur Gharana, the Benaras Gharana, and the Lucknow Gharana.

The roots of this dance form trace back to a Sanskrit Hindu text on performing arts called ‘Natya Shastra’ written by an ancient Indian Theatrologist. And musicologist Bharata Muni. Thousands of verses structured in different chapters are found in the text that divides dance into two particular forms, namely ‘nrita’ that is a pure dance that comprises finesse of hand movements and gestures, and ‘nritya’ that is a solo expressive dance that focuses on expressions.

The word Kathak is deduced from the Vedic Sanskrit term ‘Katha’ which means ‘story’ while the term kathaka that finds a place in several Hindu epics and texts means the person who tells a story. The Lucknow Gharana of Kathak was founded by Ishwari Prasad, a devotee of the Bhakti movement. It is believed that Lord Krishna came to his dreams and instructed him to develop “dance as a form of worship”. He taught the dance form to his sons Adguji, Khadguji, and Tularamji who again taught their descendants, and the tradition continued for more than six generations thus carrying forward this rich legacy that is well acknowledged as the Lucknowgrarana of Kathak by Indian literature on the music of both Hindus and Muslims.

This ancient classical dance form that was majorly associated with Hindu epics was well acknowledged by the courts and nobles of the Mughal period. The dance performed in Mughal courts however adapted a more erotic form without having many references to particular themes applied earlier that communicated religious or spiritual concepts. Improvisations were made by the dancers predominantly to entertain the Muslim audience with sensuous and sexual performances which although were different from the age-old dancing concept, contained a subtle message in it like the love of Radha-Krishna. Over time, Central Asian and Persian themes became a part of its repertoire. These included replacements of sari with a costume that bared midriff, adding a transparent veil in the costume that typified the ones worn by medieval Harem dancers and whirling while performing as done in Sufi dance. By the time the colonial European officials arrived in India, Kathak had already become famed as a court entertainment and was more of a fusion of ancient Indian classical dance form and Persian-Central Asian dance forms with the dancers being referred to as ‘nautch girls.

The emergence of colonial rule in the 18th century led to the discouragement of kathak. The social stigma associated with nautch girls added with a highly critical and despicable attitude from the Christian missionaries and British officials, who held them as harlots. In the midst of such upheaval, the families made effort in keeping this ancient dance form from dying out and continued teaching the form including training boys. The progress of the Indian freedom movement in the early 20th century saw an effort among Indians to revive national culture and tradition and rediscover the rich history of India in order to resurrect the very essence of the nation. The revival movement of Kathak developed both in the Hindu and Muslim Gharanas simultaneously, especially in the Kathak-Mishra community.

As Kathak is popular both in Hindu and Muslim communities the costumes of this dance form are made in line with traditions of the respective communities. There are two types of Hindu costumes for female dancers. While the first one includes a sari worn in a unique fashion complemented with a choli or blouse that covers the upper body and urhni worn in some places, the other costume includes a long embroidered skirt with a contrasting choli and a transparent urhni. The costume is well complimented with traditional jewellery associated with musical anklets called ghunghru. Hindu male Kathak dancers usually wear a silk dhoti with a silk scarf tied on the upper part of the body which usually remain bare or may be covered by a loose jacket. The jewellery of male dancers is quite simple compared to their female counterparts and are usually made of stone. The costume for Muslim female dancers includes a skirt along with a tight-fitting trouser called churidar or pyjama and a long coat to cover the upper body and hands. A scarf covering the head compliments the whole attire which is completed with light jewellery.

A typical Kathak performance includes a dozen classical instruments like the tabla that harmonises well with the rhythmic foot movements of the dancer and often imitates the sound of such footwork movements or vice-versa to create a brilliant jugalbandi. A manjira that is hand cymbals and sarangi or harmonium are also used most often. Some eminent personalities associated with Kathak include among others the founders of the different gharanas or schools of this form of classical dance namely Bhanuji of the Jaipur Gharana; Janaki Prasad of the Benaras Gharana; Ishwari Prasad of the Lucknow Gharana; and Raja Chakradhar Singh of the Raigarh Gharana. Shambhu Maharaj was a renowned guru of the Lucknow Gharana. His brothers Lachhu Maharaj and Acchan Maharaj were also stalwarts in the art of Kathak. One name that has almost become synonymous with modern-day Kathak dance is Pandit Birju Maharaj, a scion of the legendary Maharaj family and son of Acchan Maharaj. He is considered the leading advocate of the Lucknow Kalka-Bindadin gharana. Sitara Devi was another star of this dance form described as Nritya Samragini that is the empress of dance by Rabindranath Tagore and she continues to retain her Kathak Queen title even after death.

3. Kathakali

Kathakali is an important genre in the Indian classical dance form associated with the storytelling form of this art. It is a dance drama from the south Indian state of Kerala. The tale in the dance form is communicated to the audience through intricate footwork and impressive gestures of face and hands complimented with music and vocal performance. However, it can be distinguished from the others through the intricate and vivid make-up, unique face masks and costumes worn by dancers as also from their style and movements that reflect the age-old martial arts and athletic conventions prevalent in Kerala and surrounding regions. Traditionally this dance form was performed by male dancers only. This classical dance form is considered to have originated from temple and folk arts that trace back to the 1st millennium CE or before.

Traditionally the name of this dance form was deduced by joining two words, ‘Katha’ and ‘Kali’ where ‘Katha’ in Sanskrit means a traditional tale or story and ‘Kali’ derived from ‘Kala’ refers to art and performance. Views and opinions regarding the roots of ‘Kathakali’ vary due to its somewhat ambiguous background. The most conceived story is that ‘Ramanattam’ that developed under the auspices of Thampuran was the genesis of ‘Kathakali’ and that Thampuran refined the former to give shape to ‘Kathakali’ that has over the centuries emerged as a famous classical dance of Kerala.

Traditionally the themes of ‘Kathakali’ were based on religious sagas, legends, mythologies, folklores and spiritual concepts taken from the ‘Puranas’ and the Hindu epics. Kathakali is typically structured around ‘Attakatha’ meaning the story of attam or dance. ‘Attakatha’ are plays that were historically derived from Hindu epics like ‘BhagavataPurans’, ‘Mahabharata’ and ‘Ramayana’ which were written in a certain format that allows one to determine the dialogue portions that is the Pada part and the action portions that is the Shloka part of the performance. The latter is the poetic metre written in the third person elucidating the action portions through choreography. A dramatic representation of an ancient play is presented in a Kathakali performance which includes actor-dancers, vocalists and musicians. This age-old performance art traditionally starts at dusk and is performed through dawn with breaks and interludes and sometimes for several nights starting at dusk.

Kathakali’ incorporates the most intricate make-up code, costume, face masks, headdress and brightly painted faces among all Indian classical dance forms. Its unique costume, accessories and make-up complemented with a spectacular performance, music and lightings bringing life to the characters of the great epics and legends attract and flabbergasts both young and the old thus creating a surreal world around. The make-up code followed in ‘Kathakali’ conventionally typifies the characters of the acts categorizing them as gods, goddesses, saints, animals, demons, and demonesses among others. Kathakali encompasses seven fundamental make-up codes which are ‘Pacca’ (green), ‘Minukku’, ‘Teppu’, ‘Kari’ (black), ‘Tati’, ‘Payuppu’ (ripe) and ‘Katti’ (knife). A character with ‘Pacca’ make-up and bright coral red colored lips depicts gods, sages, and noble characters like Shiva, Krishna, Rama and Arjuna. A ‘Minukku’ make-up using orange, saffron, or yellow color depicts virtuous and good female characters like Sita and Panchali. The color code for women and monks is yellow. Black is also used for representing demonesses and unreliable characters with distinctive red patches. Evil characters like Ravana bear the ‘Tati’ (red) make-up. Headgears and face masks help emphasize the face make-up which is prepared from colors extracted from vegetables and rice paste.

- A ‘Kathakali’ performance includes various instruments that encompass three major drums namely ‘Itaykka’, ‘Centa’, and ‘Maddalam’. Music plays a significant role in this form of classical art creating variations of tones setting and corresponding to the mood of a particular scene. The voice artists also contribute significantly in the entire act by not only delivering the relevant lines but also setting the mood and context of the scene by modulating their voice to express the temperament of the character. Kavungal Chathunni Panicker, a celebrated and veteran performer of this field, is a scion of the famous Kavungal family associated with ‘Kathakali’ for six generations. Another famed ‘Kathakali’ actor Kottakkal Sivaraman, who portrays feminine characters emotes different nayika bhavas such as lasyanayika and vasakasajjika with great élan. Kalamandalam Ramankutty Nair is a seasoned ‘Kathakali’ performer who not only earned fame for portraying negative characters like Ravana and Duryodhana but also proved his mettle in characterising Lord Hanuman.

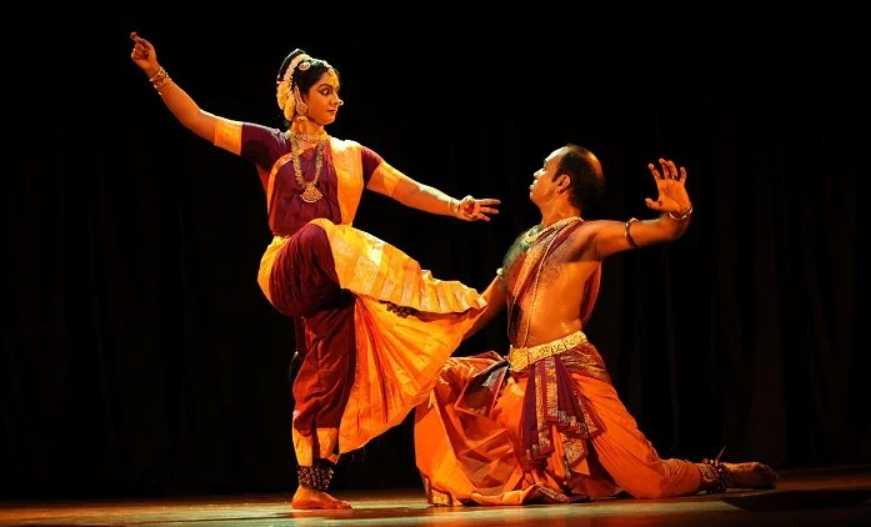

4. Kuchipudi

Kuchipudi, a pre-eminent Indian classical dance form counted among ten leading classical dance forms of India, is a dance-drama performance art that originated in a village in the Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh, India. Usually, the performance repertoire of Kuchipudi that is broadly oriented on Lord Krishna and the tradition of Vaishnavism include an invocation, dharavu – short dance, nritta – pure dance and nritya – expressive dance respectively.

The theoretical foundation of Kuchipudi is rooted back to the ancient Sanskrit Hindu text on the performing arts called ‘Natya Shastra’ which is accredited to Indian astrologist and musicologist Bharata Muni. Bharata Muni not only mentions the Andhra region in this ancient text but also attributes an elegant movement called ‘Kaishikivritti’ and a raga called ‘Andhri’ to this region.

The dance form flourished in the 16th century under the auspices of the rulers of the medieval era, which has been manifested by several copper inscriptions. Islamic invasions and establishment of the Deccan Sultanates in the 16th century and a major military defeat of the Vijayanagara Empire at the hands of the Deccan sultanates in 1565 led to the decline of Kuchipudi. The political disturbances and wars also witnessed the Muslim army demolishing temples and creating havoc in Deccan cities that led many artists and musicians to leave the place of whom around 500 families of Kuchipudi artists were given shelter by the Hindu king AchyutappaNayak of the Tanjore kingdom. Sunni Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb overpowered the Shia Sultanate in 1687 ceasing all non-Muslim practices ordering seizure and destruction of musical instruments and ban on music and dance performances in public.

The art form revived partially after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 and the subsequent decline of the Mughal Empire. British rule subjected Kuchipudi to contemptuous fun and discouragement disgracing traditional practices. Many classical art revivalists stood against discrimination and came together to revive the ancient classical dance forms. Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastri along with his guru Vempati Venkata narayana Sastri preserved Kuchipudi. Chinta Venkataramayya, another stalwart popularised the dance form through public performances. Many Western artists who came to learn Indian classical dance forms became a part of the revival movement.

The repertoire of Kuchipudi follows three performance categories namely ‘Nritta’ (Nirutham), ‘Nritya’ (Niruthiyam), and ‘Natya’ (Natyam) mentioned in ‘Natya Shastra’ and followed by all major Indian classical dance forms. ‘Nritta’ is a technical performance where the dancer presents pure dance movements giving stress on speed, form, pattern, range and rhythmic aspects without any form of enactment or interpretive aspects. In ‘Nritya’ the dancer-actor communicates a story, spiritual themes particularly about Lord Krishna through expressive gestures and slower body movements harmonized with musical notes thus engrossing the audience with the emotions and themes of the act. ‘Natyam’ is usually performed by a group or in some cases by a solo dancer who maintains certain body movements for specific characters of the play which is communicated through dance-acting.

While a male character wears a dhoti, a female character wears a colorful sari that is stitched with a pleated cloth that opens like a hand fan when the dancer stretches or bends her legs portraying spectacular footwork. Make-up is generally light and complemented with traditional jewelry. A light metallic waist belt made of gold or brass adorns her waist while a leather anklet with small metallic bells is called ghunghroo. Hair is neatly braided and often beautified with flowers or done in the Tribhuvana style that depicts the three worlds. Eye expressions are highlighted by outlining them with black collyrium. Sometimes special costumes and props are used for particular characters and plays, for example, a peacock feathered crown adorns the dancer playing Lord Krishna.

The ensemble of a Kuchipudi performance includes a Sutradhara or Nattuvanar who is the conductor of the entire performance. He recites the musical syllables and uses cymbals to produce rhythmic beats. The story of the spiritual message is sung either by the conductor or another vocalist or sometimes by the actor-dancers. The musical instruments usually include cymbals, mridangam, tambura, veena, and flute.

Indrani Bajpai (Indrani Rahman), daughter of Ragini Devi, and Yamini Krishnamurti expanded this art through public performances outside Andhra that not only garnered new students in the art form but also made it widely popular both on national and international platforms. Other imminent Kuchipudi dancers include internationally famed dancing couple, Raja and Radha Reddy, their daughter Yamini Reddy; Kaushalya Reddy; Bhavana Reddy, daughter of Raja and Kaushalya Reddy; Lakshmi Narayan Shastri; and Swapana Sundari among others.

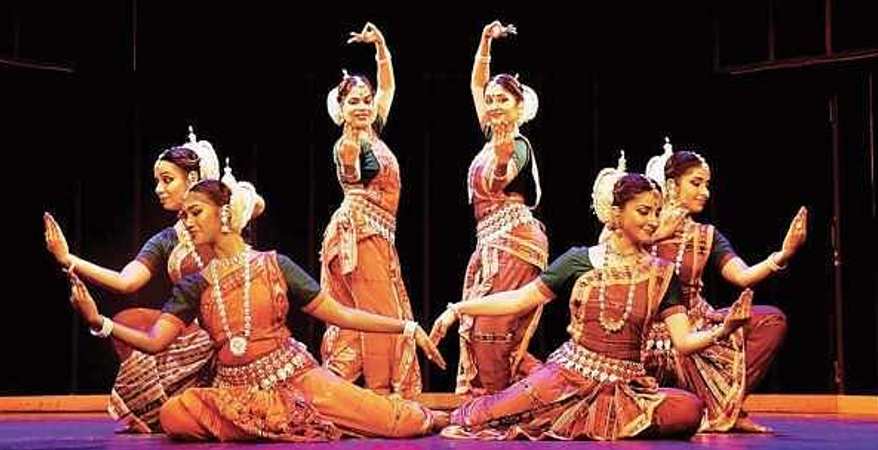

5. Odissi

Odissi or Orissi is one of the pre-eminent classical dance forms of India which originated in the Hindu temples of the eastern coastal state of Odisha in India. Its theoretical base trace back to ‘Natya Shastra’, the ancient Sanskrit Hindu text on the performing arts. Odissi is manifested from Odisha Hindu temples and various sites of archaeological significance that are associated with Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. A form of illustrative anecdote of mythical and religious stories, devotional poems and spiritual ideas emoted by dancers with excellent body movements, expressions, impressive gestures and sign languages, its performance repertoire includes invocation, nrita, nritya, natya, and moksha. This dance form includes themes from Vaishnavism and others associated with Hindu gods and goddesses like Shiva, Surya and Shakti.

Reference to four popular styles of vrittis that is methods of expressive presentations namely ‘Odra-Magadhi’, ‘Panchali’, ‘Dakshinatya’ and ‘Avanti’ is found in the text, of which Odra refers to this performing art. Sites of archaeological and historical significance like caves and temples in Puri, Konarak and Bhubaneswar bear carvings that are historical manifestations of ancient art forms like music and dance. The heritage site of Udayagiri, the largest Buddhist complex in Odisha, houses the Manchapuri cave belongs to the reign of Kharavela, the Jaina king of Kalinga from the Mahameghavahana dynasty who ruled sometime around the 1st or 2nd century BCE.

The fancy depictions of monuments, religious places and important sculptures indicate the popularity of this dance form in the medieval era even in regions of India far away from Odisha. Elaborate elucidation of hand and feet movements, different standing postures and dance repertoire can be found in Hindu dance texts like ‘AbhinayaDarpana’ and ‘Abhinaya Chandrika’. Postures of this dance form are also included in ‘Shilpaprakãsha’, an illustrated manuscript with regard to Orissan sculpture, architecture and dance figures. Sculptures and panel reliefs dating from the 10th to 14th century found in Odisha temples including the famous Jagannath temple in Puri depicts Odissi dance. The Maharis used to undergo rigorous training in the dance form from an early age and were considered propitious for religious services, performed it in temples, and enacted spiritual poems and religious plays. Compositions of the 8th century Shankaracharya or the 12th century Sanskrit poet Jayadeva’s epic poem ‘Gita Govinda’ to a great extent inspired the direction and development of present-day Odissi. Historians also mention that group of dancers from Andhra and far away Gujarat was brought to Puri thus indicating mobility between west and east.

The attacks inflicted by Muslim armies in the temples and monasteries of Odisha and other institutions in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent post 12th century not only saw plunder of these ancient sites but these raids also negatively affected the development of all art forms and freedom of artists. One such incident was the invasion of Odisha by Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1360-1361 CE), which witnessed the destruction of several temples including the Jagannath Temple in Puri which included damage and destruction of the dance halls and the dancing statues. The art forms declined during such period and whatever little survived, especially as court entertainments, was due to the patronage of some generous rulers. The Mughal and Sultanate period saw the temple dancers entertaining the family and courts of the Sultans and becoming some sort of concubines of the royals.

According to Alexandra Carter, Odissi presumably developed further in the 17th century under the patronage of King Ramachandradeva. Athletics and Akhanda (martial arts) were included and boys or youths were trained in this dance form, which traditionally was performed by women. This development led the boys and youths of Odissi called Gotipuas to get an opportunity to train at an early age and prepare for the military to combat foreign invasions. Ragini Devi states that according to historical records, the 14th century Raja of Khurda promoted the gotipuas tradition.

The 18th century saw the emergence of the rule of colonial followed by the establishment of British colonial rule in the 19th century. Such developments saw the decline of various classical dance forms which were subjected to contemptuous fun and discouragement including Odissi. Eventually, social and economic conditions associated with Devadasi culture added with contempt and despicable attitude from the Christian missionaries and British officials. Furthermore, the Christian missionaries launched an anti-dance movement in 1892 to stop such practice. The Madras Presidency under the British colonial government even banned the custom of dancing in Hindu temples in 1910. The dancers were not only subjected to disgrace but were also suppressed economically by pressurising their patrons to cease financial support.

The performance repertoire of Odissi sequentially includes an invocation followed by nritta, nritya, natya, and moksha. The invocation called Mangalacharana is performed followed by offering of flowers called Pushpanjali and salutation to mother earth referred to as Bhumi Pranam. Next in line is the performance of Batu or BatukaBhairava or BattuNrutya or SthayeeNrutya which is pure dance or nritta dedicated to Lord Shiva. It is performed only on rhythmic music without any recitation or singing. The next part is nritya which encompasses expressional dance or Abhinaya to communicate a story, song or poetry through hand gestures or mudras, emotions or bhavas and eye and body movements. The next part natya includes a dance drama based on Hindu mythological texts and epics. An Odissi performance is concluded with the dance movement referred to as Moksha that aims to communicate a feeling of emancipation of the soul.

The female dancers wear brightly coloured sari usually made of local silk adorned with traditional and local designs such as the Bomkai Saree and the Sambalpuri Saree. The front part of the sari is worn with pleats or a separate pleated cloth stitched in front to ensure the flexibility of movements of the dancer while showcasing excellent footwork. Silver Jewellery adorns the head, ear, neck, arms and wrists. Musical anklets called ghunghru made of leather straps with small metallic bells attached to them are wrapped in her ankles while the waist is tied with a belt. Feet and palms are brightened with red-colored dyes called Alta. A tikka on forehead and outlined eyes with Kajalmakes eye movements more vivid. The hair is tied in a bun and beautified with Seenthi. A moon-shaped crest of white flowers or a Mukoot that is a red crown with peacock feathers symbolizing Lord Krishna may adorn the hairdo. A male dancer wears a dhoti neatly pleated in the front and tucked between the legs that cover the lower body from the waist while the upper body remains bare. A belt adorns the waist.

The unique feature of this dance form is that it incorporates Indian ragas, both from the south and north that indicate the exchange of concepts and performance arts between the two parts of India. ‘Shokabaradi’, ‘Karnata’, ‘Bhairavee’, ‘Dhanashri’, ‘Panchama’, ‘Shree Gowda’, ‘Nata’, ‘Baradi’ and ‘Kalyana’ are the main ragas of Odissi. The musical instruments include tabla, pakhawaj, harmonium, cymbals, violin, flute, sitar and Swarmandal. The Odissi maestros who revived the art form in the late 1940s include KelucharanMohapatra, Raghunath Dutta, Deba Prasad Das, Pankaj Charan Das and Gangadhar Pradhan. The instrumental role played by Guru Mayadhar Raut saw the dance achieve classical status. Other famous exponents include disciples of KelucharanMohapatra namely SanjuktaPanigrahi, Sonal Mansingh and KumkumMohanty; ArunaMohanty, Anita Babu and AadyaKaktikar to mention a few.

6. Sattriya

Sattriyais a classical dance form from Assam which is devotional in nature as they were intended for propagation of neo-Vaishnavism. Its highlights are intense emotional fervor, and in its solo avatar now dramatic abhinaya is prominent in contrast to nritta, pure dance. It was introduced in Assam by the great Vaishnava saint and reformer of Assam, MahapurushaSrimantaSankaradeva in the 15th century A.D. He propagated the “eksharannaama dharma” (chanting the name of one God devotedly). Unlike other classical dances, the Sattriya dance has been left untouched in this regard and has been the same since its birth. Under the patronage of Sankardeva, the social and religious group known as the ‘Sattras’ (Vaishnava mathsor monasteries) formulated this dance to celebrate their beliefs which were embedded in Hinduism and its various teachings. It had its influences from folk dance forms like Ojapali, Devadasi, Bihu, Bodos, etc.

Sattriya dance tradition is governed by strictly laid down principles in respect of hastamudras, footworks, aharyas, music etc. It includes Nritta, Nritya and Natya components. The Sattriya dance form can be placed under 2 categories; PaurashikBhangi, which is the masculine style and ‘StriBhangi’, which is the feminine style. Sattriya dance is usually based primarily on the stories of Krishna-Radha relations, or sometimes on the stories of Ram-Sita. SattriyaNrityais a genre of dance-drama that tells mythical and religious stories through hand and face expressions. The basic dance unit and exercise of a Sattriya is called a MatiAkhara, equal 64 just like in Natya Shastra, which are the foundational sets dancers learn during their training. The Akharas are subdivided into Ora, Saata, Jhalak, Sitika, Pak, Jap, Lon and Khar. A performance integrates two styles, one masculine (PaurashikBhangi, energetic and with jumps), and feminine (StriBhangi, Lasya or delicate). Traditionally, Sattriyawas were performed only by bhokots (male monks) in monasteries as a part of their daily rituals or to mark special festivals on mythological themes. Today, in addition to this practice, Sattriya is also performed on stage by men and women who are not members of the sattras, on themes not merely mythological.

It has two distinctly separate streams – the Bhaona-related repertoire starting from the Gayan-BhayanarNach to the KharmanarNach, and secondly the dance numbers which are independent, such as Chali, RajaghariaChali, Jhumura, Nadu Bhangi etc. Among them, the Chali is characterized by gracefulness and elegance, while the Jhumura is marked by vigour and majestic beauty. The costume of Sattriya dance is primarily of two types: the male costume comprising the dhoti and chadar and the paguri (turban) and the female costume comprising the ghuri, chadar and Kanchi (waist cloth). Pat Silk saree (also spelt paat) is the most popular kind of saree used in this dance, which represents the locality through its various colourful motifs and designs.

Traditional Assamese jewellery is used in Sattriya dance. The jewellery is made in a unique technique in Kesa Sun (raw gold). Artists wear Kopali on the forehead, MuthiKharu and Gam Kharu (bracelets) etc. There are various musical instruments used in this dance, some of which include Khol (drum), Bahi (flute), Violin, Tanpura, Harmonium and Shankha (Conch Shell). The songs are composed by shankaradeva known as ‘Borgeets’. The musical instruments used in Sattriya are the Khols or the Drums, the Taals or the Cymbals and the Flute. Non-traditional music instruments like Mridangam and Pakhwaj were a part of the music of the Rojaghoria Chali Dance. In the present time, the violin is also commonly used in the music of Sattriya Dance.

Some of the leading male artists include Guru JatinGoswami, Guru Ghanakanta Bora, ManikBarbayan and BhabanandaBarbayan, Late Moniram Dutta, MuktiyarBarbayan, Late RoseshwarSaikiaBarbayan, Late Dr.MaheswarNeog Dr Bhupen Hazarika, Late Ananda Mohan Bhagawati while the prominent women dancers include SharodiSaikia, Indira PP Bora, Anita Sharma, AnweshaMahanta and MallikaKandali, among others.

7. Manipuri

Manipuri dance is among the major theme classical dance forms of India based on Vaishnavism and ‘Ras Lila’ portrayals, dance-dramas on love between Radha and Krishna. Other themes included in this art form are associated with Shaktism, Shaivism, and the sylvan deities called Umang Lai during the Manipuri festival ‘Lai Haraoba’. This dance form is named after the north-eastern state of Manipur, India from where it originated but it has its roots in ‘Natya Shastra’, the age-old Sanskrit Hindu text. A mix of Indian and Southeast Asian culture is palpable in this form. The age-old dance tradition of the place is manifested in the great Indian epics, ‘Ramayana’ and ‘Mahabharata’, where the native dance experts of Manipur are referred to as ‘Gandharvas’. The Manipuris perform this religious art that aims at expressing spiritual values during Hindu festivals and other important cultural occasions like marriage.

Vedic texts mention the Manipuri people as the ‘Gandharvas’ who were singers, dancers, and musicians associated with devas or the deities. Southeast Asian temples of the early medieval period bear sculptures of ‘Gandharvas’ as dancers. The region is also mentioned as ‘Gandharva-desa’ in ancient Manipuri texts. Ancient Manipuri text has fizzled out but the oral tradition of Manipuri records tracing back to the early 18th century, have references about the place in Asian manuscripts and archaeological findings speak volumes about the art. The text ‘BamonKhunthok’ that gives an account of the migration of Hindu Brahmins and Buddhists to Manipur elucidates that the practice of Vaishnavism was embraced by Manipur Kings during the 15th century CE. Later, Vaishnavism was not only adopted by King CharaiRongba in 1704 but was also declared as the state religion.

Manipuri furthered its dance tradition by incorporating dance dramas based on Lord Rama in 1734. British rule saw a decline of various Indian classical dance forms and as Manipur was annexed by the British colonial government in 189, the flourishing period of Manipuri dance art received a massive jolt. The Manipuri dancers somehow survived in the temples of the region like the Govindji temple of Imphal. Many of Tagore’s dance-dramas were given shape with the choreography of other imminent Gurus who were offered to join the center at certain points of time namely Atomba Singh, NileshwarMukherji and Senarik Singh Rajkumar.

The repertoire and basic play of this dance form revolve around different seasons. The traditional style of this art form incorporates graceful, gentle and lyrical movements. The fundamental dance movement of Ras dances of Manipur is Chari or Chali. Manipuri dances are performed thrice in autumn from August to November and once in spring sometime around March-April, all on full moon nights. While Vasant Ras is scheduled in spring when Holi, the festival of colors is celebrated by the Hindus, the other dances are scheduled around post-harvest festivals like Diwali. The themes of the songs and plays comprise of love and association of Radha and Krishna in the company of the Gopis namely Sudevi, Rangadevi, Lalita, Indurekha, Tungavidya, Vishakha, Champaklata, and Chitra. One composition and dance sequence is dedicated for each of the Gopis while the longest sequence is emphasized on Radha and Krishna. The dance drama is performed through excellent display of expressions, hand gestures and body language. Acrobatic and vigorous dance movements are also displayed by Manipuri dancers in many other plays.

The costumes for Manipuri dancers, particularly for women are quite unique from other Indian classical dance forms. A male dancer wears a bright coloured dhoti, also referred to as dhora or dhotra that covers the lower part of the body from the waist. A crown decorated with peacock feathers adorns the dancer’s head, which portrays the character of Lord Krishna. The costume of female dancers resembles that of a Manipuri bride, referred to as Potloi costumes. The most distinguished of these is the Kumil costume which is an exquisitely embellished long skirt in the shape of a barrel with a stiffened bottom. The skirt is embroidered with fine gold and silver works decorated with small mirror pieces and designs of lotus and other natural items as border prints. The top border of Kumil adorns a wavy and translucent fine skirt tied in three places around the waist in Trikasta and opens up like a flower. A velvet choli or blouse adorns the upper part of the body and a translucent veil white in colour covers the head. The dancer wears round shaped jewellery or garlands of flowers to adorn the face, hand, neck, waist and legs that synchronize well with the costume. The entire attire of the dancers performing is complimented with devotional music.

The drummers who also dance while drumming are male artists. They wear white dhoti that covers the lower part of the body from the waist and a white turban on the head. A shawl neatly folded adorns their left shoulders while the drum strap falls on their right shoulders. The musical instrument generally used in this art form includes the Pung which is a barrel drum, cymbals or kartals, harmonium, flute, Pena and Sembong. Accompanists include a singer. The language of text songs of Manipuri dance lyrics is varied including Sanskrit, Brij Bhasha and Maithili to name a few while the text songs are generally taken from the poetry of the likes of Jayadeva, Govindadas, Chandidas and Vidyapati. Imminent Manipuri performers include Guru Bipin Singh, his disciple Darshana Jhaveri and her sisters Nayana, Ranjana and Suvarna, Charu Mathur and Devyani Chalia among others.

8. Mohiniyattam

Mohiniattam or Mohiniyattam is an Indian classical dance from the state of Kerala, India. Dating back to Sanskrit’s text on performing arts, ‘Natya Shastra’, Mohiniattam adheres to the Lasya, a more graceful, gentle, and feminine form of dancing. Mohiniattam derives its name from the word ‘Mohini’, a female avatar of Lord Vishnu. Conventionally a solo dance performed by female artists, it emotes a play through dancing and singing where the song is customarily in Manipravala which is a mix of Sanskrit and Malayalam language and the recitation may be either performed by the dancer herself or by a vocalist with the music style being Carnatic.

The theoretical foundation of this dance form like other major classical dance forms of India has its roots in sage Bharata Muni’s text called ‘Natya Shastra’, a Sanskrit Hindu text that deals with performing arts. It breaks dance into two specific types, the first one being ‘nritta’ or pure dance that centers around finesse of hand movements and gestures, and the other being ‘nritya’ that features the expressive aspect of dance. The Lasya dance theme and structure are followed in Mohiniattam.

Mohiniattam evolved from the state of Kerala which also has an association with the old tradition of the Lasya style of dancing. The temple sculptures of the state are the earliest manifestations of Mohiniattam or other dance forms similar to it. The dance form developed further as a performing art during the 18th and 19th centuries during the patronage of several princely states. The book ‘The Wrongs of Indian Womanhood’ by Marcus B. Fuller published in 1900 caricatured the facial expressions and sensuous gestures emoted during temples dances. Such upheaval stigmatized all Indian classical dance forms including Mohiniattam that saw its decline in the princely states of Cochin and Travancore.

Dr. Justine Lemos, who did elaborate research on Mohiniattam, mentioned that the Maharaja had to ban the dance form under compulsion from the colonial rule and his citizens. Amidst disturbances, some female artists continued to perform the art in Hindu temples without paying heed to the political developments surrounding the art form.

The repertoire of Mohiniyattam follows Nrittaand Nrityamentioned in ‘Natya Shastra’. It follows the Lasya type of dance and displays excellence in ‘EkaharyaAbhinaya’ a form in other words a solo and expressive dance art complimented with music and songs. ‘Nritta’ is a technical performance where the dancer presents pure dance movements giving stress on speed, form, pattern, range and rhythmic aspects without any form of interpretive aspects. In ‘Nritya’ the dancer-actor communicates a story, spiritual themes through expressive gestures and slower body movements harmonized with musical notes thus engrossing the audience with the emotions and themes of the act. ‘Natyam’ is usually performed by a group communicating a play through dance-acting. Mohiniyattam’s repertoire sequence includes an invocation of Cholkettu, Jatisvaram, Varnam, Padam, Tillana, Shlokam, and Saptam.

The dancer wears a white or off-white plain sari embellished with bright golden or gold laced coloured brocade embroidered in its borders complemented with a matching choli or blouse. A pleated cloth having concentric golden or saffron-coloured bands adorns the front part of the sari from the waist. This embellishment not only lets the artist perform her spectacular footwork flexibly but also highlights it, allowing the audience to watch it from a distance. The dancer wears a golden belt around the waist. Jewellery adorns the head, hair, ears, neck, wrists and fingers. Musical anklets called ghunghru are made of leather straps with small metallic bells attached to them are wrapped in ankles. The feet and fingers are brightened with red coloured natural dyes. The face make-up of the dancer is usually light with a Hindu tikka on her forehead while the lips are vividly coloured red and the eyes are lined. The hair tied typically on the left side of the head is in a tight round chignon hairstyle and adorned with jasmine flowers ringed around the bun. Different rhythms and lyrics of vocal music are performed in this dance form. Instruments played during a Mohiniattam performance usually comprise of Kuzhitalam or cymbals; Veena; Idakka, an hourglass-shaped drum; Mridangam, a barrel-shaped drum with two heads; and flute.

Imminent exponents of Mohiniattamare Vallathol Narayana Menon, Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, Thankamony, Krishna Panicker and Mukundraja. Some present-day exponents include Sunanda Nair, SmithaRajan, granddaughter of Kalyani Kutty Amma; Radha Dutta; Vijayalakshmi; Gopika Varma and Jayaprabha Menon among others.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About Indian Classical Dance

Bharatnatyam is traditionally the word referred to as a dance form where bhava, raga, and tala are expressed.

According to Russian scholar Natalia Lidova, ‘Natya Shastra’ elucidates several theories of Indian classical dances including that of Tandava dance, standing postures, basic steps, bhava, rasa, methods of acting, and gestures.

American dancer Esther Sherman came from the West to learn Indian classical dance forms in 1930 and not only learned classical dances but also adopted the name Ragini Devi and became a part of the ancient dance arts revival movement.

Kalkaprasad Maharaj played an instrumental role in drawing international viewership of Kathak in the early 20th.

Scholar Farley Richmond mentions that many elements of ‘Kathakali’ are similar to ‘Kutiyattam’, a form of Sanskrit drama traditionally performed in Kerala.

SaskiaKersenboom, an author mentions that both ‘Bhagavata Mela Nataka’ and Kuchipudi are closely related to the traditional theatre form of Karnataka called ‘Yakshagana’ though they retain their uniqueness palpable from their varied costume, format, innovative ideas, and perceptions.

The last Shia Muslim Nawab of Golkonda, Abul Hasan Qutb Shah in 1678 aided the dancers in reviving the form by granting the Kuchipudi artists land near the village of Kuchipudi (Kuchelapuram) on condition that they take forward this ancient dance form.

The Brahmeswara Temple in Bhubaneswar and the Sun Temple at Konark are two imminent sites that showcase sculptures of dancers and musicians pertaining to the Odissi dance form.

Usha, the exalted dawn goddess in the ‘Rig Veda’ is traditionally accredited for creating female dance art and tutoring girls in the art.

The invention of the ‘Ras Lila’ dance and spreading Vaishnavism in the state of Manipur is attributed to Jai Singh Maharaja.

Rabindranath Tagore was fascinated by the performance of the dance composition of ‘Goshtha Lila’ in Sylhet in 1919 that he offered Guru Budhimantra Singh, a Manipuri dancer to join the faculty of Shantiniketan.

Development and systematization of present-day Mohiniattam was accomplished by the Maharaja of the Kingdom of Travancore, Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma.

Vallathol Narayana Menon established a dance school called ‘Kerala Kalamandalam’ in 1930 which helped the revival of Mohiniattam, Kudiyattam, and Kathakali, the three main performing arts of Kerala.