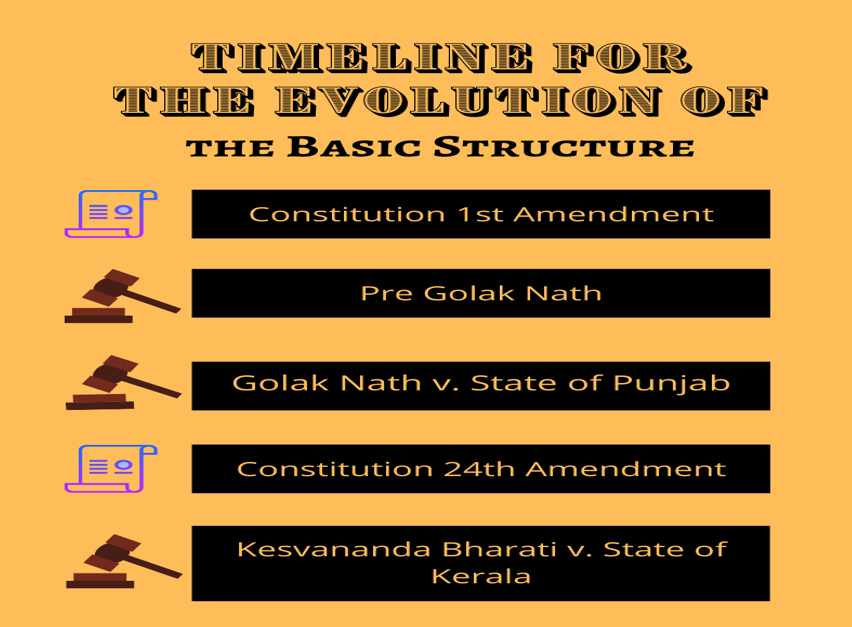

Introduction

It was the year 1950 when the constitution came into existence, a dispute arose between the Parliament (with respect to powers and horizons of Article 368) and the Judiciary. Article 13 provides for expressing provisions through which the court can strike down a law that is not in consonance with Part 3 of the Indian constitution and a pretty obvious question arose as to what is law?

Article 13 (1) gave Judiciary the right to perform Judicial Review over all those legislations that are inconsistent with or in derogation with the Fundamental Rights. It is to be noted that the concept of Judicial Review kicked in from the famous US Case named, William Marbury v. James Madison, Secretary of State of the United States. However, Article 13 (2) also mandated the Parliament and restricted their powers not to enact legislation that takes away the Fundamental Rights of Citizens. But the Government had better ideas and plans to induce agrarian reforms which could not have been possible without the help of the Judiciary and the ambiguous yet binding provisions of the Constitution.

Article 13 And Its Dispute

India at the time of Independence was in a state of shambles. We needed roads, bridges, hospitals, infrastructure and land for other developmental purposes. Also, the people were promised during the time of independence that they would be given land for agricultural purposes and improved livelihood. But the problem was that most of the land was accumulated with just a few princely rulers and zamindars and a strong need for reorganization was needed.

Two problems existed, first Article 19 (1)(f) which ensured Right to Property as a fundamental right, and secondly, the land was kept under List 2 of Schedule 7 which is the State List, which means only the state governments have a right to legislate over this subject matter. To tackle the second issue, the Central Government encouraged the State Governments to start seizing lands through reform acts. One such land reorganization act was the Bihar Land Reform Act of 1950 which aimed to take away the land from the big estate holders. In consequence, another problem arose since this Reform Act violated Article 13 (2) which states that no state shall make any laws that take away the fundamental rights of the citizens and as aforementioned, Right to Property was then, a fundamental right enshrined under Article 19 (1) (f). The state of Bihar had the competency to enact laws and hence the court could not have declared the act void under Procedural Grounds. However since the judges were extremely texted savvy in those times, they had no option but to declare the said act void. The question was brought before the Patna High Court in Kameshwar v. State of Bihar (1951). The government had no option but to anyhow overcome this Judgement and induce some other reforms. They henceforth brought in the First Amendment of 1951 and created Schedule 9.

Schedule 9 was kept outside the purview of the Judicial Review for the purpose, even if an act under Schedule 9 goes on to violate the Fundamental Rights, Judiciary can’t review the act in conflict. The purpose of bringing in Schedule 9 was to end the conflict between social welfare reforms and the infringement of fundamental rights to give substance for agrarian reforms. The first amendment also brought in place Article 31 (A) and (B) to prevent the Judiciary from taking up Constitutionality tests upon the acts under Schedule 9.

Doctrine Of Judicial Review

In India, the power of judicial review was exercised by the courts prior to the commencement of the constitution of India. The British Parliament introduced the Federal System in India by enacting the Government of India Act 1935. Under this act, both the Central and State legislatures were given plenary powers in their respective spheres. They were supreme in their allotted subjects like the British Parliament. The Act of 1935 established the Federal Court so as to function as an arbiter in central and state relationships. The Federal Court was also empowered to scrutinize the violation of the constitutional directions regarding the distribution of powers on the introduction of federalism in India. The power of judicial review was not specifically provided in the constitution but the constitution being federal, the Federal court was entrusted implicitly with the function of interpreting the constitution and determining the constitutionality of legislative acts.

Maurice Gwyer, Chief Justice of Federal Court of India in Bhola Prasad v The King-Emperor AIR 1942 F.C.R 17 P20, observed that ” we must again refer to the fundamental proposition enumerated in 1878 3 AC 889 (Reg v Borah) that Indian legislatures within their own spheres have plenary powers of legislation as large and of the same nature as those of the parliament itself, if that was true in 1878, it cannot be less true in 1942.

The Federal Court of India vigorously worked for more than a decade with wisdom and dignity and by various constitutional decisions. During the span of the decade, the Federal Court of India and other High Courts reviewed the constitutionality of a large number of legislative acts with full judicial self-restraint, insight, and ability.

The Supreme Court of India as a successor of the Federal Court of India after the commencement of the constitution of India inherited the great traditions built by the Federal Court. The constitution of India envisages a very healthy system of judicial review and it depends upon the Indian judges to act in a way as to maintains the spirit of democracy. In the present democratic set up in India, the court can not adopt a passive attitude and ask the aggrieved party to wait for public opinion against legislative tyranny, but the constitution has empowered it to play an active role and to declare legislation void if it violates the constitution.

The constitutional thinkers of India before the Indian Republic was established were of the view that in the constitution of free India there must be provisions for the supreme court with the power of judicial review. Colonel K.N.Hasker and K.M. Panikkar in their book Federal India, at P 147 said that” the supreme judicial authority should be invested with the power to declare ultra vires measures which go against the constitution.”

Explanation To Article 13 (With Historical Background And Reference To Case Laws)

- It wasn’t long before the First Constitutional Amendment was challenged. The case was Shankari Prasad v. Union of India (1951) and two questions emerged before the court. They are as follows:

- Whether the first Constitutional Amendment is a law as described under article 13?

- Whether there is a difference between ordinary legislation and constitutional amendment?

The courts were looking to declare the amendment as a law post which they can declare the amendment as unconstitutional since it was undoubtedly infringing the fundamental rights of the people. If the court failed in declaring the Amendment as a law under Article 13, that would mean they would have to check the enactment of the law on procedural grounds and they knew it beforehand that declaring the amendment flawed on procedural grounds would be a lot difficult since the law was validly enacted with a legally followed procedure by the Constituent Assembly. After all their efforts, they finally, having failed to nullify the amendment on substantive grounds, held that the amendment was enacted legally and does not violate the procedural grounds of enactment. They strictly went through the literal interpretation and failed to accept that the 9th Schedule was unconstitutional. The Court was trying to say that had the constituent assembly intended to save fundamental rights from getting amended they would have added a provision in the constitution that fundamental rights can never be amended but since no such a provision is there in the constitution hence, it is safe to assume that fundamental rights can be amended.

The problem with such a literal interpretation was that in the future even part three can be deleted by the Parliament through amendments and the court can do nothing about it. Here the Court’s interpretation was very restricted, narrow, and pedantic which could have had a disastrous situation if this case was followed as a precedent.

1. Outcomes Of Shankari Prasad Case

Constitutional Amendments cannot be declared void even if fundamental rights are violated.

Fundamental rights can be amended since the constituent assembly did not add any provision stating fundamental rights cannot be amended.

Schedule 9 is outside the purview of judicial review and Bihar Land Reform Act declared void by Patna High Court will come back to life since it was put into schedule 9.

The first instance of curtailing the decision of the Supreme Court. The first amendment had the purpose to override the decision of the Supreme Court in Kameshwar v. State of Bihar because they understood that without schedule 9 there are zero chances of having a land reform. The court can see that if they make fundamental rights rigid, a fundamental right cannot be challenged in the future as well either in a positive or a negative sense. This would have curtailed the very development of India, in the future as well.

Post this case, political weakening through coalition governments started happening in 1964 after the death of Pt. Nehru and the court got an option to present dissenting opinions and start working more efficiently. The Government kept on different state legislations under Schedule 9 to provide blanket protection to such Land Reform Acts in the name of Agrarian Reforms. Sajjan Singh challenged these amendments and hence came Sajjan Singh v. the State of Rajasthan.

Sajjan Singh challenged these amendments through procedural grounds and he contended that these amendments are making changes to the federal structure of the constitution and hence, we require the ratification of half or more than half of the states without which the amendments are unconstitutional. The second contention said that Parliament doesn’t have the authority to decide over cases under the state list (List 2) of Schedule 7 and hence there is a gross violation of procedural grounds. In response to these contentions, the Supreme Court held with respect to the first issue that there is no change in the federal structure of the constitution and hence the amendments are validly enacted. With respect to the second issue, they held that it is the state which is enacting these laws and Central Government is just ensuring protection to these laws through the amendments bringing them under Schedule 9. Chief Justice Gadkar said that the amendment is not a law under article 13 and upheld Shankari Prasad’s Judgement. Secondly, they denied both the grounds of challenges by the petitioner. The interpretation was found problematic since they stated that the amendment of the constitution is an absolute Constitutional Amendment which means, an amendment without limitation. The same thing happened with the Weimar constitution and through this lacuna, Hitler was able to destroy the then Constitution to form a new constitution.

2. Dissenting Opinions From Justice Hidayatullah And Justice Mudholkar-

Parliament has a derivative power and not a constituent power to amend and also the amending power of the Constitution is not unlimited but Article 368 grants Limited powers to the Parliament.

For the first time, the term Basic Structure (the very bedrock at which the constitution stands) was used. This said that the Parliament cannot say that by virtue of article 368, they have the right to change the basic structure of the constitution.

- While the judgment was still under process, the Parliament brought in another amendment to add ‘constituent’ under Article 368 implying that they have the constituent powers to amend the constitution. The seeds for the Basic Structure were sowed through this case by the two judges and undoubtedly a bigger conflict between the Centre and the Judiciary was yet to come.

IC Golaknath V. State Of Punjab (1968)

- The Supreme Court constituted an 11 judge bench to settle these matters for once and for all and tender to answer all the questions related to constitutional ambiguities. The petitioner challenged the judgments of Sajjan Singh and Shankari Prasad and also challenged the 1st and the 17th amendment or technically everything that was decided by the Supreme Court till 1968. Supreme Court was tasked to see as to where was the Parliament deriving its powers to amend the constitution and if the 17th amendment adding Punjab Land Reform Act under Schedule 9 was valid and constitutional.

- One of the worst judgements of the Supreme Court can be understood through the following pointers:-

Overruled both Sajjan Singh and Shankari Prasad.

Held that amendment is a law within the definition of article 13 of Indian constitution. This means that firstly, there is no difference between legislation and an amendment and secondly, you cannot use the tool of amendments to infringe fundamental rights of the citizens.

Through this judgement prospective overruling was invented. Meaning effect of judgement will come into effect from the date of IC Golaknath judgement and not from the date of Sajjan Singh judgement. Government had started agrarian reforms and if the judgement had retrospective effect back to Sajjan Singh, all confiscated land had to be returned and would have created confusion.

To answer the question as to where is the power to amend, they went to Article 246 and 247 which gives the Parliament the power to make laws (not the power to amend) and is guided by schedule 7. The said dealt with Lists under Schedule 7 and it was held that Parliament can make laws with respect to list 1 and list 3 (Central and Concurrent Lists). Item 97 of List 1 talks about subsidiary powers of the Parliament to amend the constitution. This is where they traced the powers of the Parliament to amend the constitution. When article 246 and 247 of Indian constitution are read, it says, subject to the other provisions of Indian constitution. However, Article 368 starts with ‘notwithstanding any other provision’ and happens to be a non- obstante clause with overriding effects. The problem with such an interpretation was that the Parliament when trying to amend the Constitution in future, would have had to keep all the articles and schedules and provisions of the Constitution in mind, which could not have been avoided in case the Judiciary had traced the powers to Article 368.

Lastly, they also held that Parliament cannot touch the fundamental rights and cannot be modified and are sacrosanct under Part 3 which cannot be interfered with. Through this interpretation, they had put an absolute embargo on the amending powers of the Constitution due to which Right to Property could have never been removed from Part 3 of Right to Education could have never been a part of the Constitution under Article 21 A. This was also the first time when Substantive Grounds were recognized and applied.

This infuriated Parliament and the 24th and 25th Amendments were quickly enacted to reverse the consequences of Golaknath’s judgment. Under 24th Amendment, Article 13 and Article 368 were changed with respect to granting Constituent powers of the constitution and limiting the scope of Judicial Review. With respect to the 25th Amendment, they limited the rights of people to demand a constitutional check in cases of Land reform and reorganizations.

The thirst for powers and land reforms didn’t quench in the Central Government nor did the Judiciary prevent itself from entering directly into the battlefield. Shankari Prasad, Sajjan Singh, and IC Golaknath all followed some real bad times of proved incompetence by the Indian Supreme Court. The Supreme Court was under tremendous pressure from both the Executive’s rise in power and the impregnable quest of authority to legislate. In 1973, the Supreme Court was vested with some real duty to clear all the ambiguities and settle this anomaly between the Government and the Judiciary, for once and for all. The Golaknath judgment had an 11 judge bench and to overrule the badly established precedents, a 13 judge bench was needed to come to the conclusion as to what all comes under the amending powers of the Parliament.

The Historical Judgement Of Kesavananda Bharati V. State Of Kerala (1973)

- Highest ever Constitutional bench of 13 judges to answer the anomalies of all the previous judgments and amendments, headed by Chief Justice AK Sikri. Also known as the judgment where the minority opinion of Justices Hidayatullah and Mudholkar became the majority opinion.

Questions Before The Court-

Whether IC Golaknath a good law? – The court held that no; it is not and should be overruled.

Does the Parliament have the constituent power to amend the constitution and where do they get this power from?- 24th 25th amendment added ‘constituent power’ to Article 368. The court said it wasn’t needed and that we would still be trying to search for such inherent powers under Article 368 only. They were trying to bring in their powers equal to the power of the constituent assembly however, they failed to recognize that the constituent assembly’s power was derived from the Preamble and the Preamble happened to be a salient feature of the constitution which is beyond the reach of the Parliament. Hence they can never even try changing the Preamble. The Constituent Assembly’s power was to form the constitution, however, Article 368 just grants the power to amend or modify the already formed provisions of the constitution, and that Article 368 does not give Parliament the power to form a new constitution. The court held that they should not try looking at deriving the constituent power to amend the constitution since the original constituent powers vested with the Constituent Assembly and in no way could the Parliament derive these powers through amendments.

Is there any conflict between the Fundamental Rights and DPSPs? – 24th and 25th Amendments stated that DPSPs are more powerful since nothing enshrined under the DPSPs can be challenged. Court held that fundamental rights and DPSPs are complementary to each other and have their own woven hands to work upon.

Whether the Amendment is a law under Article 13?- Amendment is not a law under Article 13 and there exists a clear line of difference between legislation and an amendment.

To what extent is the power vested with the Parliament to amend? – The 13 judge bench got divided equally with 6 on each side and 1 judge being neutral. 6 judges said they have unlimited powers whereas 6 said that they have limited powers under Article 368. Justice Khanna, one of the judges to say that the Parliament has limited powers, was highly influenced by the teachings of Professor Peter Conrad who was in India during the pronouncement of this case. Justice Khanna introduced this new concept of the said Professor which was never before recognised and was an absolute academic theory. He said that the amending powers of the Parliament are subject to the Basic Structure Doctrine which does not include the Right to Property.

- Justice Khanna also stated that the Basic Structure Doctrine says you may change any provision of the Constitution but you must not change the basic structure or the basic idea or the fundamentals on which the constitution is standing upon. The Judges were talking about a person who has an identity and living in a society. They said that you can change his clothes, his hairstyle, spectacles, ornaments but if you take away his limbs he becomes a different person altogether. Justice Khanna held that the parliament should not make any such amendment through which the constitution loses its importance after the amendment. He said that Parliament should not use their powers to emasculate, destroy or damage the basic structure of the constitution and that the old constitution should and must survive even after the amendment without changing the basic tenets of the constitution. Along with Procedural Grounds, the Judiciary added Substantive grounds for the Parliament to keep in view before bringing in amendments, which was the Basic Structure Doctrine. Both the grounds were mandated to be satisfied before the amendment can be called to be a validly enacted amendment. Judges said that the validity or the constitutionality of the Legislation/amendment will be decided by the Judiciary on case to case basis and that the Government can maybe through an amendment, one day, try to delete the entire Part 3 of the Constitution but, that will in no way take away the rights of the citizens/ persons since the rights are guaranteed not by the text of the Constitution but by the Basic Structure Doctrine on the sole basis of being born as a human being.

Settlement- Permanent Or Momentary?

After this judgment, the Parliament brought in the 44th Amendment to the Constitution to remove the Right to Property from Article 19 (1) (f), throwing it to Article 300(A) giving a mere Constitutional/ Legal right recognition to it.

It is undoubtedly true that the strife between the Judiciary and the Parliament caused the Government to find out a lot of grey areas in the constitution to satisfy their needs. It is also true that the Indian Constitution happens to be the lengthiest hand-written Constitution in this world but the vagueness can never be eliminated. The US Constitution despite being centuries old has just some 30 amendments to date. The strife led the Government to look for some even darker areas and impose a nationwide emergency soon after Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975) which is also called the darkest period of our democracy. One such democracy was the vagueness with respect to amending powers and the need for agrarian, industrial reforms which was the need of the hour at that time.

Thankfully Keshavanand Bharti provided and acts as good precedence since it was never again felt by the Court to overrule it. Who knows at what time, will the Government lookout for some other grey area in some other provision of the constitution to overrule the Kesavananda Bharati case by setting up a 15 judge bench.

Rama Rajya & The Basic Structure Doctrine

Each part of the Constitution begins with art that traces our 5,000-year-old history. The intricate gold pattern on the front and back cover borrows from Ajanta murals. This was a time when the worship of personified powers (Agni, Indra, Surya) was common practice. The Gupta period is said to be the Golden Age of India. At that time, India was contributing towards 25 percent to world GDP and held the first position for around 1,000 years.

The freedom struggle is depicted by a series of heroes starting with Rani Lakshmibai. The Constitution of India that is Bharat had pictures of Shri Rama, Sita Devi, and Sri Lakshmana returning from Lanka to establish Rama Rajya at Ayodhya. Article 363 prevents the courts from interfering with any treaties or agreements entered into by an Indian ruler before the constitution came into effect. On 13 October 2017, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, in a matter concerning the rights of Swami Ayyappa, the Sabarimala deity, referred several questions to a Constitution Bench. In the process, it disturbed a settled Kerala High Court judgment based on a Public Interest Litigation.

The new Constitutional Morality doctrine is against the spirit of Constitutional Rama Rajya. It weakens Article 26, which deals with the rights of all religious denominations to manage their own religious affairs. The ancient Mathas which protected Sanatana Dharma during multiple invasions can perish if subjected to judicial reform.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About Basic Structure Doctrine

The Basic Structure of our Indian Constitution (though sometimes confused with the Preamble to the Constitution) cannot be amended. It is free from the Executive’s scrutiny.

The Basic Structure Doctrine was formulated by Justice Khanna in the year 1973 by means of delivering an opinion through the landmark case of Keshavanand Bharati v. the State of Kerala.

The Constitution has “basic features” was first theorized in 1964, by Justice J. R. Mudholkar in his dissent, in the case of Sajjan Singh v. the State of Rajasthan. He wondered whether the ambit of Article 368 included the power to alter a basic feature or rewrite a part of the Constitution. This is how this doctrine was first idolized.

The doctrine of basic structure is nothing but a judicial innovation to ensure that the power of amendment is not misused by Parliament. The idea is that the basic features of the Constitution of India should not be altered to an extent that the identity of the Constitution is lost in the process.

To overrule this precedent, the Supreme Court will have to formulate a 15 judge bench. Only larger benches can overturn a previous judgment and the Keshavanand Bharati Case carried 13 Supreme Court judges.

The Supreme Court generally sits with an odd number of judges to the bench. The reason behind this remains that even a number of judges, in some cases, could lead to an equal number of judges for and against a ruling. This would create confusion and wastage of time for an institution with a huge workload already.

None of the provisions of the Constitution, however, restrains or prevents the Supreme Court of India to establish an even number of judges to a bench.

Article 13 gives The Indian Supreme Court, the right to conduct Judicial Reviews over legislations or amendments brought by the Parliament.

This right is almost impregnable and the Judiciary can exercise this right over multiple administrative, parliamentary, executive, and judicial functions.

Right to Judicial Review is not applicable to Schedule 9 of the Indian Constitution. However, Schedule 9 is no longer Pandora’s box and Basic Structure Doctrine does strictly apply to Schedule 9 as well.

The 42nd Amendment to the Constitution is also called the ‘Mini Constitution’ in lieu of the multiple changes to the structure of the Constitution it aimed to bring during the period of emergency but was however overturned.

Post Keshavanand Bharati case, the case of IR Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu was used by the Supreme Court to thoroughly explain what Basic Structure actually is and how the Parliament can prevent itself from going against the doctrine.

Article 368 even today, casts no limitation upon the restricted powers of the Parliament to amend, modify or repeal any legislation and even the Constitution of India, subject to the practice of Judicial Review.

Some FAQs Or Also Ask Question

What comes under the Basic Structure Doctrine?

Basic Structure Doctrine is often confused with the ‘Preamble’ to the constitution. However Preamble along with the basic tenets forms the Basic Structure which cannot be amended. Basic Structure Doctrine is a judicial theory and not something which can actually be found in the Constitution explicitly.

What is the Basic Structure Doctrine and how is it related to the amendments to the Constitution?

Basic Structure Doctrine restricts amendments to violate the basic code of the Indian Constitution. In short, Basic Structure implies that no amendment should ever try to change the pillars on which the Constitution stands, which will lead to an altogether new constitution otherwise.

Has the basic structure been defined in the Constitution?

No. There is no explicit mention of Basic Structure Doctrine in the Indian Constitution. This is the brainchild of Justice Khanna who was further motivated by Professor Peter Conrad and was introduced through the 1973 judgement of Keshavanand Bharati v. State of Kerala.

In which famous case the basic structure principle of the Indian Constitution is involved?

Although there is a series of judgements which paved the way for that specific judgment but the judgement introducing this concept is ‘Keshavanand Bharati v. State of Kerala’.

Can the Parliament change the basic structure principle of the Indian Constitution?

Basic Structure since does not form a part of the constitution, cannot be amended ever. This is a judicial tool of checking constitutionality and is immune to amendments.