- Umang Sagar

- Law, Recent article

Assisted Suicide

The deliberate termination of one’s own life is known as suicide. It is a final act of behavior that is most likely the result of multiple causes interacting with each other. However, this definition falls short of capturing the concept’s complexity and the various ways in which terms are used across studies. It’s a complex entity, with biology, genetics, and environment all playing a role as risk factors. Suicide can also be explained in terms of socio-political factors. Suicide’s consequences include not just the loss of life, but also the mental, physical, and emotional toll it has on family and friends. Other consequences and costs are to public resources because those who attempt suicide frequently require medical and mental assistance.

It is estimated by The World Health Organization (WHO) that almost one million people die by suicide each year worldwide, representing an annual global suicide mortality rate of 16 per 100,000. Suicide claims around 32,500 lives per year in the United States alone. Suicide attempts are becoming increasingly common, in addition to the rising number of suicide deaths. Suicide attempts are connected with severe morbidity and are a key predictor of subsequent suicide. They are believed to be twenty-fold more common in the general population.

Assistance in suicide refers to knowingly and willfully providing a person with the knowledge, methods, or both necessary to commit suicide, such as counseling regarding fatal drug doses, prescribing such lethal doses, or assisting someone in committing suicide. In short, suicide with the assistance of another person is known as assisted suicide. Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is suicide with the assistance of a physician or other healthcare practitioner. The physician’s assistance is usually limited to issuing a prescription for a deadly dose of medications if it is established that the person’s situation qualifies under the physician-assisted suicide regulations in that location.

It is important to note that assisted suicide differs from Euthanasia, often known as mercy killing, in which the person dying does not cause their own death but is killed to save further suffering. Euthanasia can be consensual, non-voluntary, or involuntary, and can occur with or without agreement. Euthanasia and assisted suicide are often seen as part of the physicians’ professional duty and consistent with the goals of medicine which include ‘‘healing, promoting health and helping patients achieve a peaceful death’’ (Miller & Brody, 1995, p. 12). The Hippocratic oath, which prevents physicians from prescribing deadly amounts of drugs to patients, is at the heart of some of the strongest opposition to physician-assisted suicide. Pain relief, which is frequently cited as a primary reason for requesting euthanasia or assisted suicide, should be provided through standard medical care, with the understanding that physicians may need more training in pain management and hospice care (Brody, 1992; Capron, 1996; Quill, Cassel, & Meier, 1992; Thomasma, 1996).

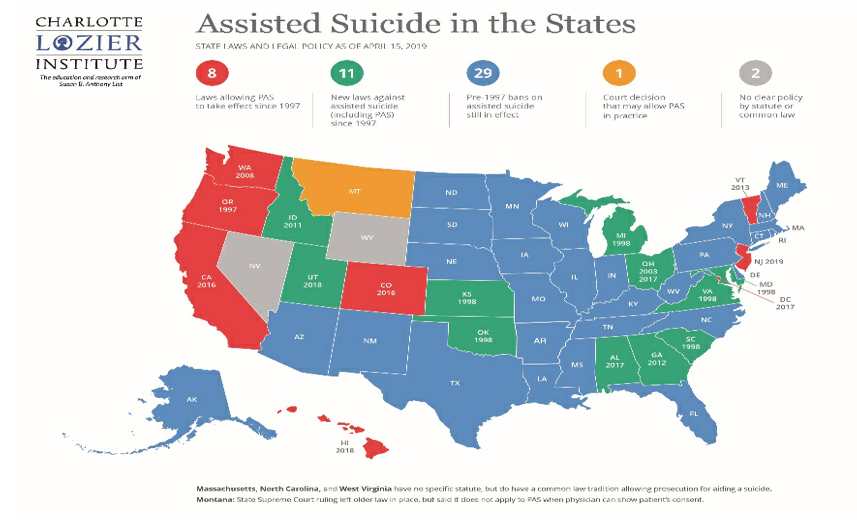

In several countries, including Austria, Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, portions of the United States, and parts of Australia, physician-assisted suicide is permitted under specific circumstances. Colombian, German, and Italian constitutional courts have all approved assisted suicide, but their governments have yet to legislation or regulate the practice. A terminal diagnosis is not required in some countries, such as Canada, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and voluntary euthanasia is also permitted.

Ethics

Medical ethics, sometimes to a greater extent than the law, establishes physicians’ responsibilities to patients and society. Physicians owe patients duties based on the ethical concepts of doing what is best for the patient, avoiding or minimizing harm, respect for patient autonomy, and promotion of fairness and social justice. The right to refuse treatment, even life-sustaining therapy, is strongly supported by both medical ethics and the law. The goal is for the patient to avoid or discontinue therapy that he or she believes is incompatible with his or her desires and interests. After the denial, death occurs naturally as a result of the underlying condition.

The principle of respect for patient autonomy, as well as a broad interpretation of a physician’s duty to relieve suffering, are among the ethical arguments in favour of physician-assisted suicide. Physician-assisted suicide is viewed by supporters as a compassionate act that honours the patient’s choice while also fulfilling obligation of nonabandonment. Opponents argue that the profession’s most consistent ethical traditions emphasise care and comfort, that physicians should not intentionally end a person’s life, and that physician-assisted suicide requires physicians to violate specific prohibitions as well as the general duties of beneficence and nonmaleficence. Such breaches are seen contradictory to the physician’s role as healer and comforter.

The ethical debates about the nature of the patient-physician relationship—a relationship that is inherently unequal due to power differentials and the vulnerability of illness—physicians’ duties and the role of the medical profession in society reflect ethical arguments about the nature of the patient-physician relationship.

Although the CMA Code of Ethics does not explicitly prohibit euthanasia or assisted suicide, the code has historically been considered to do so. The articles of the code listed below are relevant to CMA policy on this issue.

“Consider first the well-being of the patient.” This means that the care of patients, in this case, those who are terminally ill or who face an indefinite life span of suffering or meaninglessness, must be physicians’ first consideration.

“Provide appropriate care for your patient, even when cure is no longer possible, including physical comfort and spiritual and psychosocial support.”

“Provide your patients with the information they need to make informed decisions about their medical care, and answer their questions to the best of your ability.”

“Respect the right of a competent patient to accept or reject any medical care recommended.”

“Ascertain wherever possible and recognize your patient’s wishes about the initiation, continuation or cessation of life-sustaining treatment.”

“Recognize the profession’s responsibility to society in matters relating to . . . legislation affecting the health or well-being of the community . . .”

“Inform your patient when your personal values would influence the recommendation or practice of any medical procedure that the patient needs or wants.”

Issues

Fear in the medical community also exists that trust in physicians would be undermined if they have the social sanction to intentionally cause death (Miller & Brody, 1995). Another common issue expressed in the literature is that if assisted suicide is legalized, we will be on a “slippery slope.” The concept of “the slippery slope” relates to the belief that permitting assisted suicide as a voluntary choice will lead to the legalization of active voluntary euthanasia and the far more heinous practices of involuntary and nonvoluntary euthanasia. As a result, there may not be a free option, or even a choice at all, for those who are marginalized and vulnerable in our society, such as people living with AIDS or the elderly.

The question that arises here is who will decide whose life is valuable enough to spend health-care dollars on and whose life is disposable? Should these judgments be left to the impersonal techniques and limits of managed care bureaucrats, who are increasingly scrutinizing medical care in order to cut costs?

- Many opponents of physician-assisted suicide have religious objections.

The Roman Catholic Church, for example, believes the intentional termination of life to be morally wrong and in violation of the Fifth Commandment (“Thou shalt not kill”).

Judaism places a high value on life preservation and does not condone suicide or assisted suicide. Furthermore, there is non-faith-based criticism of PAS. To begin with, it can be deemed merely objectionable due to the immorality of killing.

One morally questionable argument is that allowing physician-assisted suicide will reduce healthcare expenses. However, according to one study, legalizing physician-assisted suicide would only save around 1% of total healthcare spending. Supporters of physician-assisted suicide argue that allowing a patient to choose his own death allows for organ donation to non-terminally ill patients who require transplants. Multiple organs degenerate, eventually losing function, as a result of terminal conditions. As a result, we can conclude that proponents see some reasoning in the need for the living to use these organs while they are still viable when a terminally ill patient is prepared to die in a way that will help another person live. As a result, advocates say that legalizing physician-assisted death will save lives. However, because it commodifies the worth of human life, this technique clearly raises serious ethical concerns, which the majority of clinical ethicists would find unpleasant.

It is illegal in many jurisdictions to assist someone in committing suicide. Supporters of physician-assisted suicide want those who help someone die voluntarily to be protected from criminal prosecution for manslaughter or other offences.

Attitude Of Healthcare Professionals

Despite the popular belief that allowing euthanasia and assisted suicide is primarily to relieve pain in the terminally ill, data from the Netherlands’ Remmelink Commission (Emanuel, 1994; Van der Maas, Van Delden, Pinjnenborg & Looman, 1991) found that loss of dignity was the primary reason given by patients requesting assistance in death in a study of 405 physicians. Case information on the last one or two of the physicians’ patients who had requested euthanasia or assisted suicide was acquired on a total of 207 distinct patients in a survey of 828 physicians (Back, Wallace, Starks, & Pearlman, 1996). The doctors thought that potential loss of control, becoming a burden, putting pressure on others for some or all of their personal care, and loss of dignity were the most common reasons for requesting euthanasia or assisted suicide. Patients who were in significant pain, physical discomfort, extreme suffering, dependent on others, or confinement to bed sought euthanasia rather than assisted suicide more often. The most common responses from doctors were to have a more in-depth discussion with the patient and to increase treatment of physical complaints. As a result, simply treating pain control issues will not alleviate many patients’ fears and concerns about the end of their lives. Social workers can use their abilities to interact with patients, families, and health care providers in this type of circumstance to encourage, coordinate, and support multidisciplinary dialogue about issues that affect patients’ quality of life.

According to a poll conducted in the United Kingdom, 54 percent of General Practitioners are either favorable or indifferent on the issue of assisted dying legislation. According to a similar poll published in the BMJ on Doctors.net.uk, 55 percent of doctors endorse it. The British Medical Association (BMA), which represents doctors in the UK, is opposed to it.

In a 2000 anonymous, confidential postal survey of all General Practitioners in Northern Ireland, it was discovered that over 70% of those polled rejected physician-assisted suicide and voluntary active euthanasia.

Opposition To Patient Assisted Suicide In USA

Despite the American Medical Association’s resistance to PAS on the grounds that it is contradictory to a doctor’s duty as healer, modern attitudes regarding death and dying believe the subject of assisted suicide to come within the purview of clinical practice, as PAS suggests. Physicians in the United States are divided on assisted suicide, with opposition linked to rising religion and certain moral and ethical ideals.

The Oregon Death With Dignity Act clearly identifies physicians as the primary gatekeepers of assisted suicide, laying out responsibilities for attending physicians such as ensuring that each patient who requests assisted suicide is capable, acts voluntarily, makes an informed decision, and is dying of a terminal disease (defined as an incurable and irreversible disease that will cause death within six months). Psychiatrists and other practitioners who may be approached to advise on the integrity of a patient’s request for aid in dying should take their opinions seriously because of the significant obligation conferred by Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act.

Arguments for and against PAS touch on a wide range of moral convictions, illustrating the contradiction between ideals such as autonomy, paternalism, fairness, and human life value. Although the debate might be addressed in political, social, and medical terms, most people’s feelings on the subject simply come down to a fundamental moral conviction about whether or not a person can help another person end his or her life. Debates that center on such fundamental convictions tend to polarise people, and the resulting discussion is frequently characterized by rhetoric and prejudice. Common ground and compromise appear increasingly unlikely as views become more alienated. Scientific evidence, despite being frequently neglected or dismissed in many circumstances, has the potential to inform our thinking on subjects that raise moral and ethical concerns. Evidence can characterize the conditions and effects connected with various opinions, yet it is not conclusive. Some of the most contentious aspects of the debate over assisted suicide include fears or questions that can be illuminated with actual evidence.

PAS In UK

The provision of means to assist another person in dying is illegal in the United Kingdom. The law is unambiguous in that it prohibits a third person from assisting someone in ending their life; the third party will almost certainly face criminal charges. In England and Wales, the nature of the offence is defined by the 1961 Suicide Act, which makes attempting or successfully committing suicide no longer a criminal offence. However, s.2. (1) of the Act says that helping suicide is still a crime punishable by up to 14 years in jail.

PAS In India

Despite the fact that there are few research on PAS in India, a survey claims that 60 out of 100 Indian doctors (28 men and 32 women) responded to a questionnaire. There were 26 Hindus, 23 Christians, and 10 Muslims among the doctors, who had an average age of 35.4 years and 10.2 years of experience. Overall, 26.6 percent agreed that euthanasia may be an option for people with motor neuron disease, while 25% agreed that euthanasia could be used for cancer patients. Four Christian doctors and 16 Hindu doctors (8 male and 8 female) backed euthanasia.

To our knowledge, no study has been conducted to analyse the attitudes of the general public and professionals in particular who may be involved in caring for some members of society who might consider discussing PAS or euthanasia.

Fasts are protected under the constitution, according to Jain leaders, who claim that people have the right to die with dignity. This discussion has sparked a debate in India about the right to die, where euthanasia is illegal and suicide is a criminal punishable by imprisonment for those who attempt suicide.

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) governs the legal position of PAS and euthanasia in India. The IPC addresses both active and passive euthanasia, as well as PAS. Active euthanasia is a crime under Section 302 (murder punishment) or at the very least Section 304 of the Penal Code 1860. (punishment for culpable homicide not amounting to murder). In India, PAS’ legal standing would be abetment of suicide under IPC Section 306 (abetment of suicide). So, officially, anyone considering euthanasia or PAS must go through Indian courts, and the courts have never issued a clear ruling permitting a PAS to proceed.

Policies

There is currently no government policy on physician-assisted suicide or active euthanasia. President Clinton, on the other hand, approved a law prohibiting the use of any federal funds, including Medicaid funds, to pay for physician-assisted suicide. Oregon is the only state with a statute enabling assisted suicide in certain situations; it was approved by voters in 1994 as a public vote. An appeal was filed against the Oregon statute, which was found illegal by a federal district judge.

The American Medical Association (AMA), the American Nurses Association (ANA), the National Hospice Organization (NHO), and the Academy of Hospice Physicians are all opposed to the legalization of physician-assisted suicide. According to the AMA Position Statement, using any active technique to end a patient’s life is not permitted (1995).

According to the American Medical Association (1995), there is an “overriding public interest in safeguarding vulnerable persons from death’s irreversible finality.” The American Medical Association (AMA) released its first policy on end-of-life care, which included a shift away from protecting life at all costs and toward honoring patients’ choices for a dignified death (the policy reiterates its opposition to assisted suicide) (Mauro, 1997). The ANA position statement from 1995 declares that “the nurse undertakes no act deliberately to terminate the life of any person,” and that participating in assisted suicide is unethical.

The NHO (1995) opposes euthanasia and assisted suicide and additionally promotes the expansion of hospice services to people who are not terminally ill but have chronic conditions with a need for pain management.

NASW Policy Statement

The primary premise to guiding social workers is client self-determination, according to the NASW (National Association of Social Workers) policy statement on End-of-Life Decisions. ‘‘Choice should be intrinsic to all aspects of life and death’’ (NASW, p. 61, 1996). To maximize self-determination, social workers must be well-versed in and adhere to state laws governing end-of-life decisions, such as living wills, durable powers of attorney for health care, and laws prohibiting physician-assisted suicide. In healthcare settings, social workers are instructed to foster dialogue between the healthcare team and patients and families in order to discuss and resolve concerns regarding proper medical treatment in a responsible manner (NASW, 1996).

In discussing the full range of options available to patients and families in an end-of-life situation (counseling, advance directives, nursing home placement, hospice services, physician-assisted suicide if legal), social workers are not to promote any one option in particular, according to NASW policy. Respect for self-determination is a primary principle for social workers, and it already mandates that they not push any particular options, regardless of the situation, so patients should have a free choice that should be protected. The NASW policy does not hold a stance on euthanasia or assisted suicide, but it does suggest that social workers could be included in discussions about the practices if they become legal.

According to the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) policy on end-of-life decisions (1996), social workers should be allowed to withdraw from discussions of assisted suicide and related topics with patients/families if they are uncomfortable with ideas that contradict their personal beliefs and values and do not believe they can approach the situation objectively. They also have an ethical obligation to recommend patients/families to another expert who can talk to them about their concerns. Being conscious of one’s own values is a prerequisite for referring elsewhere.

In addition, the end-of-life policy states that it is inappropriate for social workers to participate in assisted suicide while acting in their professional role (as they may be criminally liable). If their state allows it, social workers may be present during an assisted suicide if the patient requests it (NASW, 1996).

Take Of Some Famous Personalities On PAS Stephen Hawking

Sept. 18, 2013- Stephen Hawking, the brilliant theoretical physicist who has been on life support for 23 years battling ALS, has fueled a deep divide in the right-to-die movement by saying that those who have a terminal illness and are in pain should be able to end their lives “without prosecution.

“We don’t let animals suffer, so why humans?” he told the BBC this week, noting that there should be adequate protection so that no one is condemned to die against their wishes.”

“There must be safeguards that the person concerned genuinely wants to end their life and they are not being pressurized into it or have it done without their knowledge or consent as would have been the case with me,” he told the interviewer, according to the Guardian newspaper.

Movies And Documentaries On Assisted Suicide

1. ‘Exit: The Right To Die’

- The emphasis of Fernand Melgar’s sincere documentary about assisted suicide, “Exit: The Right to Die,” is so restricted that it feels like a stuffy promotional film for the Swiss group Exit A.D.M.D., which assists terminally ill individuals in ending their lives. “Exit: The Right to Die” has such a narrow emphasis that it never addresses the religious problems underlying assisted suicide. And it merely makes a vague reference to legal matters.

2. “The Good Death” – Documentary, 2018

- Janette is gravely ill and wants to die peacefully. She has to make plans to travel to Switzerland before her sickness makes it impossible. Her son Simon has Muscular Dystrophy as well, therefore he understands her decision much better than his sister Bridget. If there is no solution for this condition, he will be forced to make the same decision as his mother. Janette’s children try to persuade her to postpone her death.

3. ‘Me Before You’

- In the movie, based on the book of the same name, Will Traynor, played by Sam Claflin, gets paralyzed from the neck down in a motorbike accident. His caregiver, Louisa Clark, is played by Emilia Clarke. He eventually decides to travel to Switzerland, a prominent assisted suicide location. The movie was protested against in Connecticut. “It conveys the message that suicide is preferable to having a disability,” said Stephen Mendelsohn of Second Thoughts Connecticut.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About Assisted Suicide

1997, a ballot measure in Oregon authorised physician-assisted suicide. A comparable law was enacted in Washington State via a ballot proposal in 2008, and it went into effect in 2009.

The laws in Washington and Oregon invite elder abuse. The most obvious explanation is that when the lethal dose is provided, there is no oversight. For example, no witnesses are necessary for death; the death can take place in solitude. In this case, an heir or someone else who stands to benefit financially from the patient’s death can deliver the deadly dose to the patient without her consent.

A patient must be an adult with a life expectancy of six months or less, be competent to make an informed healthcare decision and be able to take their own medication.

Two doctors must confirm that the patient has six months or fewer to live, not because of age or handicap, but because of a fatal illness. The absence of compulsion must be confirmed by two doctors and two independent witnesses.

Since 2000, Oregon’s suicide rate has been “rising dramatically,” excluding suicides committed under the state’s physician-assisted suicide law.

There has not been a single substantiated case of abuse or coercion, nor any civil or criminal charges filed related to the practice in the more than 20 years since the first law was enacted in Oregon and an additional 40+ years of combined evidence and cumulative data from laws passed in other jurisdictions.

It enables patients to make their own decisions. The patient is the one in command. They’ve asked for the drug. They accept it. They also have the ability to change their minds at any time.

It enhances the quality of end-of-life care Studies reveal that in jurisdictions providing medical aid in dying, palliative (“comfort”) treatment improves for patients — and their families. Far more people benefit from medical aid in dying than those who choose to use it. Even knowing medical help in dying as an option reduces fear and anxiety, according to research, even for individuals who never use it.

Doctors are in favour of providing medical assistance to those who are dying. According to a Medscape poll conducted in November 2020, more than half of physicians (55%) endorse the practice.

The American population wants medical assistance when it comes to dying. According to a Gallup poll conducted in May 2020, over three out of four Americans (74%) agree. Most demographic groupings show high support. People who go to church, people of all ideological views (conservatives, moderates, and liberals), people from both political parties, and people of all colors and ethnicities all favor the practice. Since Gallup first asked the issue in 1947, support has nearly doubled.

Medical aid in dying is currently authorized in eleven jurisdictions. They include Oregon (1994), Washington (2008), Montana (2009), Vermont (2013), California (2015), Colorado (2016), the District of Columbia (2016), Hawai‘i (2018), New Jersey (2019), Maine (2019) and New Mexico (2021).

People who ask for medical assistance in dying are thoroughly tested to rule out depression, which impairs judgement.

Since the Oregon Death with Dignity Act went into force in 1997, a total of 67 Oregonians have had prescriptions written under the law, with 1275 people dying as a result of consuming the drugs. 143 patients used medical aid in dying in 2017, with the projected rate of Death with Dignity Act fatalities at 39.9 per 10,000 total deaths1, which is similar to previous years.