- The 1984 Delhi Anti-Sikh Pogrom refers to a four-day pogrom that took place in various parts of India’s capital, New Delhi, causing the death of nearly 3,000 Sikhs. It followed the assassination on October 31, 1984, of Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister of India, by her two Sikh bodyguards, in revenge for Operation Blue Star. This event – probably the most deadly in the violent history of Delhi – remains highly controversial. Twenty-five years later, most of its instigators and perpetrators remain unpunished despite the claims of various survivors and human rights groups that the pogrom was orchestrated by officials of the Congress Party with the connivance of the Delhi administration and police. Anti-Sikh violence was not restricted to Delhi but also took place in other Hindi-speaking heartland states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana. This case study nonetheless focuses on Delhi as the pattern of violence was set up there and then reproduced elsewhere.

Introduction

- The relationship between the Sikh community of Punjab and the Indian central government had been marked by tension since India’s accession to independence on August 15, 1947. Considering themselves as the great losers and victims of the Partition of the British Raj, Sikhs have often interpreted the policies of the Indian national government as discriminatory and harmful to their faith and community. They resented the inclusion of Sikhs in the frame of the Hindu religion under article 25 of the 1950 Indian Constitution and were outraged by the central government’s refusal to grant their demand for the creation of a Punjabi Suba (a Punjabi-speaking province where Sikhs would be the majority) while similar demands were granted to other states in the frame of the linguistic reorganization of states’ boundaries during the mid-fifties. Starting in 1950, the Punjabi Suba movement finally achieved its goal in 1966, when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi promulgated the tri-partition of the Indian Punjab between Punjab (where Sikhs represent nearly 60% of the population whereas they form only 2% of the national population), Haryana (gathering some Hindi-speaking districts) and Himachal Pradesh (getting adjacent Hindi-speaking districts). Then, first in 1973 and again in 1978, following the Emergency, New Delhi discarded and unduly stigmatized as secessionist the demands from the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) – the Sikh premier political party – contained in the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. It requested decentralization of power, provincial autonomy, industrial development, better allocation of Punjab’s river waters, abolition of the ceiling for the recruitment of Sikhs in the Army, attribution of Chandigarh as the capital of Punjab only (to this date Chandigarh is the capital of both Punjab and Haryana, and a Union territory), etc. It is during this period that Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale Ji, the head of the religious seminar Dam DamiTaksal, tapped into Sikh discontent and emerged as the iconic leader of the struggle against the «Hindu conspiracy» which was said to undermine the Sikh religion and community. During the early 1980s, Punjab witnessed a rising confrontation when Hindu and Sikh civilians as well as police officers were hit by a wave of killings. It is attributed by the Indian government to alleged Sikh militants. In 1982, at the time when the SAD was launching a popular and pacifist movement called Dharm Yudh Morcha, Bhindranwale Ji moved with his followers to the Harmandir Sahib Complex, the holiest shrine of Sikhism, in order to spread his message among the Sikhs of Punjab. Indira Gandhi, who was worried by his rise, though it was allegedly sponsored by some of her close advisors such as GianiZail Singh as a means to weaken the SAD, ordered the Indian Army to attack the Harmandir Sahib Complex and capture Bhindranwale. The assault was called Operation Blue Star and took place on June 6, 1984. It resulted in the total destruction of the Akal Takht Sahib – the highest site of authority within Sikhism – as well as the library, which contained original copies of Sikhism’s most sacred texts. Moreover, Bhindranwale and most of his followers were killed. The Sikhs, whether supporters of Bhindranwale or not, were shocked by this attack on their most revered place of worship and outraged by the scale of violence. According to official accounts, Operation Blue Star caused 493 civilian deaths and 83 army casualties. But both eyewitnesses and scholars question this figure as thousands of pilgrims were within the Harmandir Sahib Complex on the very day of the assault as it was, purposely or not, the anniversary of the martyrdom of the fifth Guru, Shri Guru Arjun dev Ji. This event propelled a cycle of extreme violence, which lasted until 1995, between the Indian state forces and some Sikh armed militants fighting for an independent Sikh state in Punjab named Khalistan. While violence unleashed during the Khalistan movement was mostly concentrated in Punjab, another event – the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her two Sikh bodyguards on October 31, 1984, in retaliation for her sending the army to the Shri Harmandir Sahib – set off a second sequence of mass violence, this time in New Delhi, the capital of India. It lasted for four days and resulted in the death of nearly 3,000 Sikhs.

Instigators And Perpetrators

- Contrary to what is commonly believed, this pogrom was not the result of a spontaneous reaction of the masses due to anger caused by the death of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. It was rather an organized, politically engineered action involving Congress politicians, Delhi police officers and Hindu civilians. As far as the decision-makers are concerned, it is difficult to provide sufficient evidence to incriminate officials from the central government is Rajiv Gandhi, who succeeded his mother as Prime Minister of India, and his cabinet. However, Rajiv Gandhi’s infamous comment on the pogroms, «when a mighty tree fall, the earth shall shake», as well as Home Minister Narasimha Rao’s inaction can be interpreted at least as passive acquiescence to the violence. The pogrom nonetheless seems not to be part of a conspiracy by the Indian government but was rather «organized for the government by forces which the government itself had created» (Van Dike, 1996: 206). In the final analysis, the mass-scale nature of the violence in such a short span of time implies that the attack might have been planned, possibly since Operation Blue Star (Kothari, 1985) and underlines the existence of an institutional riot structure (Brass, 2006: 63-105) readily available in Delhi.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was shot at her residence, No. 1 Safdarjung Road, by her two Sikh bodyguards, Beant Singh and Satwant Singh, at 9:15 AM on October 31, 1984. After the attack, she rushed to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) where she died from her injuries a couple of hours later. Following the announcement of her death on All India Radio (AIR), people started to gather around AIIMS during the afternoon. They were shouting heinous slogans such as «Khunkabadla, Khun Se Lenge » («Blood for blood») or «Sardar Qaum Ke Ghaddar » («Sardars – another name for Sikh men – are the nation’s traitors») which were broadcasted all day through the state-owned TV channel Doordarshan. Some scattered incidents occurred in and out of the area, particularly in the neighboring constituency of Congress Councilor, Arjun Dass. The car of President of India GianiZail Singh, himself a Sikh, was stoned when he reached AIIMS around 5:20 PM. Some Sikhs were pulled out of cars and buses, beaten, and their turban burnt. However, no killings occurred on that day, meaning that violence was a localized and spontaneous reaction of a mob angered at the death of Indira Gandhi.

Both the scale and nature of violence changed between October 31 and November 1. During this night, several Congress (I) –(I for Indira) senior and local leaders held meetings in order to mobilize their local supporters. They were highly instrumental in the instigation and organization of the pogrom. Some of them, such as Congress (I) Member of Parliament (MP) Sajjan Kumar and Congress (I) Trade Union Leader and Metropolitan Councilor LalitMaken provided alcohol and money to rioters, encouraging them to perpetuate the killings. Rioters were also provided with free transportation from their locality on the outskirts of Delhi to the city. Trucks, tempos, and other means of transportation, including Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) buses in South Delhi and even police vehicles, were extensively used to carry the mobsters to those areas of the city where Sikhs were concentrated. Congress (I) leaders supplied them with lathis (bamboo sticks), uniformed-size iron bars, knives, Trishul (trident), clubs, and highly inflammable substances such as kerosene. Because kerosene was far too expensive for the assailants to afford, it was provided by kerosene dealers belonging to the Congress (I), such as the president of Sultanpuri A/4 Block Brahmanand Gupta. Finally, they were also supplied with the names and addresses of Sikhs available from electoral and school registration as well as ration lists. This information had to be read by Congress (I) leaders to the mostly illiterate assailants.

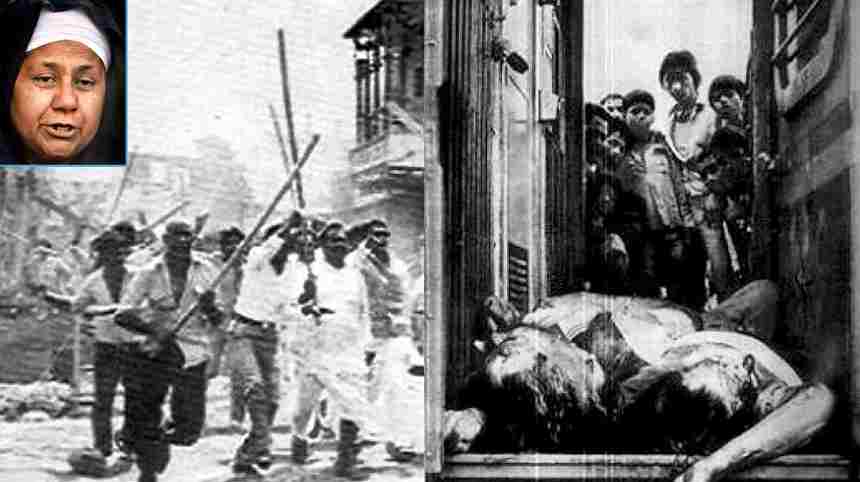

- Not only did Congress (I) leaders organize meetings to gather perpetrators, distribute weapons and identify targets, but also some even acted as direct leaders for the mob Besides the three names mentioned earlier, the names of Congress (I) officials accused of leading mobs and inciting mobsters to kill Sikhs that can be read in most of the affidavits filed by victims and survivors are the following: Dharam Dass Shastri, Jagdish Tytler, H.K.L Bhagat, Balwan Khokhar, Kamal Nath, brothers Tek Chand and Rajinder Sharma, Dr. Ashok, Shyam Singh Tyagi, and Bhoop Singh Tyagi. The attacks started simultaneously in various parts of the citybetween 8:00 and 10:00 AM on November 1. The first targets in the localities populated by Sikhs were the Sikh Gurudwara (places of worship). The Shri Guru Granth Sahib (Sikh scriptural canon) was desecrated by attackers who urinated on it and then burnt down the Gurudwaras. Sikh properties were targeted as well as symbols of the Sikh faith. Turbans, uncut hair and beards were the next target, meaning that members of the community were directly attacked. The modus operandi of killings was meticulous, systematic and reproduced everywhere across the city. Assailants raided previously identified Sikh households, grabbed the men and pulled them out. They started by tearing off their turbans, beat them with iron nods and/or knives and finally neck-laced them with a tire, which was set on fire. The bodies or remnants were left on the spot before being collected three days later in order to hide the scale of killings (Grewal, 2007: 167). Afterwards, the properties were looted and set on fire. Women and children were generally spared though some were also killed and many of them gang-raped, often in front of their relatives. The Sikhs who were seen by the mobs in the streets were mercilessly chased and killed through the same technique. The Congress (I) leaders who led the mobs were often assisted on the ground by gang leaders drawn from the underworld of the J.J. (jhuggi-jhonpri or «huts and shacks») colonies. These colonies later renamed resettlement colonies were set up by the Congress at the time of the Emergency in order to relocate people living in slums outside the city centre. The colonies became an important vote bank of the party. Local politicians started to use local criminals for political rallies and in order to intimidate opponents. These gangs provided the local Congress leaders with mostly poor and illiterate mercenaries ready to perpetrate the carnage. Some backward castes of Jats and Gujjars and Schedule castes men such as Bhangis from the urban villages around Delhi also participated in the massacre, mostly driven by the desire to loot and by their hatred of the well-off Sikhs of Delhi’s posh areas. Killing, looting and arson went on unabated the entire day and even increased on November 2. The crowd stopped trains to pull out Sikh passengers pulled kill them. The day after, violence tended to decrease in the centre of Delhi but remained massive in the resettlement colonies. Finally, by November 4, law and order was almost restored despite some episodic attacks.

- The Delhi police were not only conspicuous by its absence but also eventually encouraged and even indulged in violence. More police were in charge of Indira Gandhi’s funeral procession than of the security of Sikhs. Although the city was placed under curfew, neither police nor the army was there to enforce it. The army was deployed only on the afternoon of November 1 but abstained from using fire against rioters. In some cases, police and rioters were actually working hand in hand as expressed by this slogan: «Police hamare saath hai » («The police is with us»). Other slogans, this time of extermination, were also shouted on that day: «Maar Deo Salon Ko » («Kill the bastards»), «Sikhon do mar do aur loot lo » («Kill the Sikhs and rob them») and «Sardar koi bhi nahin bachne pai » («Don’t let any Sardar escape»). The police even disarmed Sikhs who tried to protect themselves and their relatives by force. These were either handed over to mobsters or sent back home unprotected when the police did not kill them immediately. Moreover, the police refused to record people’s complaints and FIRs (First Information Reports) after the pogrom. When it was done, it was in such a manner that the reports were useless for prosecution. With regards to the prosecution, the Nanavati Commission report had already stated: «There is ample material to show that no proper investigation was done by the police even in those cases which were registered by it. In fact, the complaint of many witnesses is that their complaints or statements were not taken by the police and on the basis, thereof separate offenses were not registered against the assailants whom they had named. Even while taking their statements, the police had told them not to mention the names of the assailants and only speak about the losses caused to them. There is also material to show that the police did not note down the name of the assailants who were influential persons [Jagdish Tytler and Balwan Khokhar]». The police also contributed to the spreading of rumors, therefore aggravating the situation. The first rumor to be spread in order to stir up the desire for revenge of Hindus was that Sikhs were dancing the Bhangra, setting off firecrackers, and distributing sweets when they heard the news of Indira Gandhi’s death. Phone calls by police officials and touring police vans with loudspeakers broadcasted the fake rumors that Sikhs had poisoned the water supply and that a train had arrived from Punjab full of dead Hindus. Once violence unleashed itself, other rumors were disseminated according to which crowds of Sikhs were creating havoc in the city and urging Hindus to defend themselves.

Contrary to what is commonly believed, this pogrom was not the result of a spontaneous reaction of the masses due to anger caused by the death of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. It was rather an organized, politically engineered action involving Congress politicians, Delhi police officers, and Hindu civilians. As far as the decision-makers are concerned, it is difficult to provide sufficient evidence to incriminate officials from the central government Rajiv Gandhi, who succeeded his mother as Prime Minister of India, and his cabinet. However, Rajiv Gandhi’s infamous comment on the pogroms, «when a mighty tree fall, the earth shall shake», as well as Home Minister Narasimha Rao’s inaction can be interpreted at least as passive acquiescence to the violence. The pogrom nonetheless seems not to be part of a conspiracy by the Indian government but was rather «organized for the government by forces which the government itself had created» (Van Dike, 1996: 206). In the final analysis, the mass-scale nature of the violence in such a short span of time implies that the attack might have been planned, possibly since Operation Blue Star (Kothari, 1985), and underlines the existence of an institutional riot structure (Brass, 2006: 63-105) readily available in Delhi.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was shot at her residence, No. 1 Safdarjung Road, by her two Sikh bodyguards, Beant Singh and Satwant Singh, at 9:15 AM on October 31, 1984. After the attack, she rushed to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) where she died from her injuries a couple of hours later. Following the announcement of her death on All India Radio (AIR), people started to gather around AIIMS during the afternoon. They were shouting heinous slogans such as « Khun ka badla, khun se lenge » («Blood for blood») or «Sardar Qaum Ke Ghaddar » («Sardars – another name for Sikh men – are the nation’s traitors») which were broadcasted all day through the state-owned TV channel Doordarshan. Some scattered incidents occurred in and out of the area, particularly in the neighboring constituency of Congress Councilor, Arjun Dass. The car of President of India GianiZail Singh, himself a Sikh, was stoned when he reached AIIMS around 5:20 PM. Some Sikhs were pulled out of cars and buses, beaten, and their turban burnt. However, no killings occurred on that day, meaning that violence was a localized and spontaneous reaction of a mob angered at the death of Indira Gandhi.

Both the scale and nature of violence changed between October 31 and November 1. During this night, several Congress (I) –(I for Indira) senior and local leaders held meetings in order to mobilize their local supporters. They were highly instrumental in the instigation and organization of the pogrom. Some of them, such as Congress (I) Member of Parliament (MP) Sajjan Kumar and Congress (I) Trade Union Leader and Metropolitan Councilor LalitMaken provided alcohol and money to rioters, encouraging them to perpetuate the killings. Rioters were also provided with free transportation from their locality on the outskirts of Delhi to the city. Trucks, tempos, and other means of transportation, including Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) buses in South Delhi and even police vehicles, were extensively used to carry the mobsters to those areas of the city where Sikhs were concentrated. Congress (I) leaders supplied them with lathis (bamboo sticks), uniformed-size iron bars, knives, Trishul (trident), clubs, and highly inflammable substances such as kerosene. Because kerosene was far too expensive for the assailants to afford, it was provided by kerosene dealers belonging to the Congress (I), such as the president of Sultanpuri A/4 Block Brahmanand Gupta. Finally, they were also supplied with the names and addresses of Sikhs available from electoral and school registration as well as ration lists. This information had to be read by Congress (I) leaders to the mostly illiterate assailants.

Not only did Congress (I) leaders organize meetings to gather perpetrators, distribute weapons and identify targets, but also some even acted as direct leaders for the mob Besides the three names mentioned earlier, the names of Congress (I) officials accused of leading mobs and inciting mobsters to kill Sikhs that can be read in most of the affidavits filed by victims and survivors are the following: Dharam Dass Shastri, Jagdish Tytler, H.K.L Bhagat, Balwan Khokhar, Kamal Nath, brothers Tek Chand and Rajinder Sharma, Dr. Ashok, Shyam Singh Tyagi, and Bhoop Singh Tyagi. The attacks started simultaneously in various parts of the city between 8:00 and 10:00 AM on November 1. The first targets in the localities populated by Sikhs were the Sikh Gurudwara (places of worship). The Shri Guru Granth Sahib (Sikh scriptural canon) was desecrated by attackers who urinated on it and then burnt down the Gurudwaras. Sikh properties were targeted as well as symbols of the Sikh faith. Turbans, uncut hair, and beards were the next target, meaning that members of the community were directly attacked. The modus operandi of killings was meticulous, systematic, and reproduced everywhere across the city. Assailants raided previously identified Sikh households, grabbed the men, and pulled them out. They started by tearing off their turbans, beat them with iron nods and/or knives, and finally neck-laced them with a tire, which was set on fire. The bodies or remnants were left on the spot before being collected three days later in order to hide the scale of the killings (Grewal, 2007: 167). Afterward, the properties were looted and set on fire. Women and children were generally spared though some were also killed and many of them gang-raped, often in front of their relatives. The Sikhs who were seen by the mobs in the streets were mercilessly chased and killed through the same technique. The Congress (I) leaders who led the mobs were often assisted on the ground by gang leaders drawn from the underworld of the J.J. (jhuggi-jhonpri or «huts and shacks») colonies. These colonies later renamed resettlement colonies were set up by the Congress at the time of the Emergency in order to relocate people living in slums outside the city center. The colonies became an important vote bank of the party. Local politicians started to use local criminals for political rallies and in order to intimidate opponents. These gangs provided the local Congress leaders with mostly poor and illiterate mercenaries ready to perpetuate the carnage. Some backward castes of Jats and Gujjars and Schedule castes men such as Bhangis from the urban villages around Delhi also participated in the massacre, mostly driven by the desire to loot and by their hatred of the well-off Sikhs of Delhi’s posh areas. Killing, looting, and arson went on unabated the entire day and even increased on November 2. The crowd stopped trains to pull out Sikh passengers pulled kill them. The day after, violence tended to decrease in the center of Delhi but remained massive in the resettlement colonies. Finally, by November 4, law and order were almost restored despite some episodic attacks.

The Delhi police were not only conspicuous by its absence but also eventually encouraged and even indulged in violence. More police were in charge of Indira Gandhi’s funeral procession than of the security of Sikhs. Although the city was placed under curfew, neither police nor the army was there to enforce it. The army was deployed only on the afternoon of November 1 but abstained from using fire against rioters. In some cases, police and rioters were actually working hand in hand as expressed by this slogan: «Police hamare saath hai » («The police is with us»). Other slogans, this time of extermination, were also shouted on that day: «Maar Deo Salon Ko » («Kill the bastards»), «Sikhon do mar do aur loot lo » («Kill the Sikhs and rob them») and «Sardar koi bhi nahin bachne pai » («Don’t let any Sardar escape»). The police even disarmed Sikhs who tried to protect themselves and their relatives by force. These were either handed over to mobsters or sent back home unprotected when the police did not kill them immediately. Moreover, the police refused to record people’s complaints and FIRs (First Information Reports) after the pogrom. When it was done, it was in such a manner that the reports were useless for prosecution. With regards to the prosecution, the Nanavati Commission report had already stated: «There is ample material to show that no proper investigation was done by the police even in those cases which were registered by it. In fact, the complaint of many witnesses is that their complaints or statements were not taken by the police, and on the basis, thereof separate offenses were not registered against the assailants whom they had named. Even while taking their statements, the police had told them not to mention the names of the assailants and only speak about the losses caused to them. There is also material to show that the police did not note down the name of the assailants who were influential persons [JagdishTytler and BalwanKhokhar]». The police also contributed to the spreading of rumors, therefore aggravating the situation. The first rumor to be spread in order to stir up the desire of revenge of Hindus was that Sikhs were dancing the Bhangra, setting off firecrackers, and distributing sweets when they heard the news of Indira Gandhi’s death. Phone calls by police officials and touring police vans with loudspeakers broadcasted the fake rumors that Sikhs had poisoned the water supply and that a train had arrived from Punjab full of dead Hindus. Once violence unleashed itself, other rumors were disseminated according to which crowds of Sikhs were creating havoc in the city and urging Hindus to defend themselves.

Victims

The victims of this pogrom were all members of one particular religious minority: the Sikhs. Sikhs, particularly males, are easily recognizable due to their distinctive appearance, and so are their places of worship. According to the 1981 census, they were 393,921 Sikhs in Delhi, representing 6.33% of the population (Misra, 1974: 14). In October 1984, the Sikh population approximated 500,000, which is 7.5% of the total population, while Hindus made up 83% of the population of Delhi. Most Sikhs were migrants from West Punjab who settled in Delhi at the time of Partition. Before that their population amounted to only 1.2% (Harlock, 2007: 115). Tilak Nagar in the north of Delhi has the most important concentration of Sikhs: approximately 300,000 of its 450,000 inhabitants (ibid.: 115). Other clusters of Sikhs could be found in the resettlement colonies east of the Jamuna river and north of the city. While the Sikh population increased in Delhi, going up from 290,000 in 1971 to 550,000 in 2001, their actual percentage decreased from 7.2% to 4% of the city’s population. The decrease was particularly pronounced during the decade between 1981 and 1991 (Grewal, 2007: 16). Besides, although Sikhs formed a small and decreasing majority (59 %) in the state of Punjab (ibid.: 16), they represent barely 2% of India’s population, meaning nearly 20 million people (Census of India, 2001).

Delhi’s Sikhs are streaming from every cross-section of socio-economic classes – weavers, potters, construction workers, small and big business entrepreneurs, educated elite, military personnel, white- and blue-collar employees, wholesalers, retailers, and transporters. They are present in every part of Delhi but can be seen increasingly when one leaves the urban and wealthy center in direction of the poor margins of the city. The class angle of killings was particularly significant. It is actually in the farthest outskirts of Delhi that violence was the most extreme and deadly. The worst affected areas were the resettlement colonies of East, West, and North Delhi such as Trilokpuri, Kalyanpur, and Mangalpuri, but the middle-class neighborhoods of Connaught Place, Vasant Vihar, Maharani Bagh, New Friends Colony, Lodhi Colony, and Hauz Khas were not spared. However, there, more looting than killing took place.

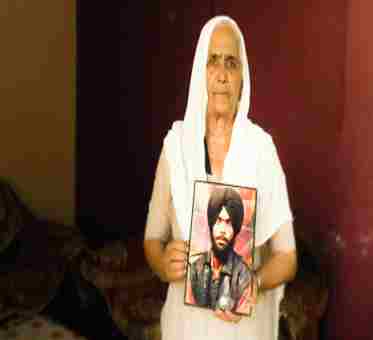

The first official estimate of casualties in Delhi was only 325 killed (including 46 Hindus). The Hindustan Times reported these numbers on November 11, 1984. However, three years later, the official death toll was said to be 2,733, leaving over 1,300 widows and 4,000 orphans (Kaur, 2006: 5). Besides, more than 50,000 Sikhs also left Delhi after the pogrom. The Sikh victims in Delhi had actually nothing to do neither with the militancy in Punjab nor with the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Quite on the contrary, many of them had even been close supporters of the Congress. Among Sikhs, victims were carefully discriminated against on the basis of gender and class. The main targets were the low-class Sikh males between 20 and 50 years of age of the poor East Delhi Trans-Jamuna localities. This gendered profiled targeting means that the mobsters were willing to attack Sikh male procreators and Sikh families’ breadwinners. Women were also subjected to violence, mainly in the form of rape. Particularly aimed at was the honor of families by showing the incapacity of Sikh males to protect their women which were aimed at. The survivors, mainly widows, orphans, and old people, went to relief camps, Gurudwaras, and relatives’ houses but the Indian state refused to take adequate measures to provide relief to survivors.

Witnesses

The main witnesses of this pogrom are the survivors, mainly Sikh women, children and old people. Their personal experiences and recollections of the violence are presented in the thousands of affidavits they filed. These affidavits were used by the various commissions set up after the pogrom and in charge of inquiring about it.

The survivors’ personal accounts and those of relatives of victims were also collected by human rights activists and published in their reports such as the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) and the People’s Union for Democratic Rights’ Who are the Guilty? (See Annex 2) and Citizens for Democracy’s Truth about Delhi Violence. Some reporters also provided first-hand accounts of the killings. Rahul KuldipBedi and Joseph Maliakan of The Indian Express were the first journalists to enter Trilokpuri, where the most gruesome massacre occurred on November 2. Eminent novelists such as Amitav Ghosh in his The Ghost of Indira Gandhi and Khuswant Singh, himself a Sikh, also wrote about what they had witnessed during the pogrom.

Scholars also played an important role in collecting the memories of survivors. Uma Chakravarti and NanditaHaksar conducted several interviews with survivors for their book The Delhi Riots (Chakravarti&Haksar, 1987). Veena Das worked on the experience of the survivors of Sultanpuri from November 5, 1984, till July 1985 (Das, 1990). More recently Jyoti Grewal (Grewal, 2007) and Angela Harlock (Harlock, 2007) have conducted interviews with survivors, mostly women, in TilakVihar, also known as the Widows’ Colony since many widows were relocated there.

Memories

The memory of the anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi is rather characterized by its absence than by its presence. The commissions set up to inquire about the events have mainly contributed to imposing silence rather than a remembrance by whitewashing the Congress officials. In August 2005, following the reception of the Nanavati Commission’s report, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, himself a Sikh, apologized to the Sikh community as well as to the Indian nation for the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom: «On behalf of our government [United Progressive Alliance (UPA)-government led by the Congress], on behalf of the entire people of this country, I bow my head in shame that such a thing took place… I have no hesitation in apologizing to the Sikh community. I apologize not only to the Sikh community but to the whole Indian nation because what took place in 1984 is the negation of the concept of nationhood enshrined in our Constitution… we as a united nation can ensure that such a ghastly event is never repeated in India’s future.» (Manmohan Singh, 2005) Although an apology can be interpreted as an expression of accountability, if not culpability, the fact that Manmohan Singh never refers to the role played by Congress deprived it of all its meaning. Moreover, he rejected remembrance of the killings and advised the survivors to bury their memories and move on: «By reliving that, by reminding us, again and again, you do not promote the cause of national integration, of strengthening our nation sense for security» (ibid.).

The guardians of the memory of November 1984 are primarily the Sikh widows and their children. The numerous widows located in TilakVihar are commonly referred to as ‘Chaurasiye‘ or 84-ers, hence conferring a new kind of collective identity to the survivors of the pogrom. Interestingly, the traumatic experience of the survivors is often mediated by the memory of the Partition massacres of 1947. 1984 is conceived as the Second Migration, an intra-national one this time, towards Punjab, the first being in 1947. Both are deemed unforgettable and at the same time unspeakable. But what is for Sikhs the most unbearable is the feeling of injustice and hopelessness fed by the 24 years of impunity for perpetrators of the carnage. While the only response of the Indian state is to provide survivors with financial compensation, what Sikhs ask for is the prosecution of instigators and perpetrators. This implies that justice must come first. Only then can an appeased memory be born.

In recent years, a few movies and documentaries dealing with the pogrom were released such as Amu directed by Shonali Bose in 2005, 1984 Sikhs’ Kristallnacht edited by Parvinder Singh in 2004, and The Widow Colony – India’s Unsettled Settlement directed by Harpreet Kaur. The year 2007 also witnessed the consecutive publication of two books on the 1984 anti-Sikh pogrom, respectively Jyoti Grewal’s Betrayed by the State and Manoj Mitta and H.S. Phoolka’s When a Tree Shook Delhi. This renewed interest in the event is however not received in the same manner by victims who feel that it only serves the interests of scholars, journalists, and activists, hence changing nothing about their plight. The main legacy of this pogrom among Sikhs is thus a strong sense of fear, humiliation, bitterness, and alienation towards Hindus.

Not Riots But Murder/General Interpretations Of The Facts

The official, as well as popular or academic naming of the events, tends to undermine and distort the nature of the violence perpetrated in Delhi between November 1 and 4, 1984. The commonly used term «riots» is a misnomer meant to reduce the violence to a simple and spontaneous outburst of grief and anger and to describe it as a conflict between ethnic and religious groups. Actually, the obviously orchestrated and evidently targeted nature of the violence, and also the fact that the Sikhs of Delhi could and indeed have barely retaliated, make it far more accurate to define it as a «pogrom».The first kind of general interpretation given for this violence was that it was the result of a spontaneous outburst of popular anger and grief of Indian citizens over the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. This ‘official narrative’ was particularly publicized by the Congress government. Indira Gandhi’s son and successor in the post of Prime Minister of India himself justified this stance when he stated that «Some riots took place in the country following the murder of Indiraji. We know the people were very angry and for a few days, it seemed that India had been shaken. But, when a mighty tree falls, it is only natural that the earth around it does shake a little» (quoted in Negi, 2007). Moreover, another factor is often added to this interpretation according to which Sikhs had brought this violence on themselves, deserving «to be taught a lesson» because of violence perpetrated against Hindus by Sikh militants in Punjab during the previous years.

Another kind of general interpretation, though minor, is that it was essentially a law and order problem with a strong class base as it was members of lower castes who looted wealthy localities with the complicity of the police-criminals-politicians nexus (Van Dike, 1996: p. 204). There was an echo of this interpretation in the Misra Commission report of the inquiry, which failed to prosecute anyone.

A last opposite general explanation put forward by most human rights organizations is that this pogrom «far from being spontaneous expressions of ‘madness’ and ‘grief and anger’ at Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination as made out by authorities, was rather the outcome of a well-organized action marked by acts of both commissions and omissions on the part of important politicians of the Congress (I) at the top and by authorities in the administration» (PUCL-PUDR, 1984: 1). Citizens for Democracy even went further by stating that this pogrom was primarily meant «to arouse passion within the majority community – Hindu chauvinism – in order to consolidate Hindu votes in the election held on December 27, 1984, which was indeed massively won by the Congress (I) (Rao & al., 1985: 1).

- However, it seems not enough to explain this pogrom only as ‘state-sponsored’ or in terms of a Congress conspiracy as this explanation is unable to account for the differentiated spatial structure of the violence (Das, 2005: 93). Das argued that only an analysis of the articulation between the spectacular events of collective violence and the everyday life in places where violence occurred can help us understand some phenomena. The question remains why in a locality such as Sultanpuri violence spread only in some areas and not all of them. As a result, the local structure of caste cleavages, kinship networks, and economic relationships must be studied in order to understand why the violence occurred where it had.

Government Stand

Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led BJP government at the Centre on Thursday told the Parliament that the Centre has made a provision of Rs 4.5 crore in the Union Budget for the enhanced compensation for 1984 anti-Sikh riots victims.

The Ministry of Minority Affairs said in the Lok Sabha that the Union government had earlier introduced a rehabilitation package to provide relief to victims of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. The scheme contained ex-gratia payment of Rs 3.5 lakhs for each death case and Rs 1.25 lakhs in case of injuries.

“The scheme also contained a provision for the State governments to grant pension to widows and old aged parents of death victims at the uniform rate of Rs 2500/month, for whole life. The expenditure on payment of pension was to be borne by the State government,” the ministry added.

However, the compensation was enhanced in 2014 by the Modi government to Rs 5 lakh from earlier 3.5 lakh per deceased, who died during the ’84 anti-Sikh riots.

“The Central government had in 2014 introduced a scheme for grant of enhanced relief of Rs 5 lakh per deceased, who died during the ’84 anti-Sikh riots. “In Union Budget 2021-22, provision of Rs 4.5 cr made for payment of enhanced compensation to next of kin of deceased of ’84 riots,” it said.

“For payment of enhanced ex-gratia amount, the States/UTs would disburse the money from their own funds, and Ministry of Home Affairs would reimburse the amount to the concerned State/UT Government on receipt of utilization certificate,” the ministry added.

But this does not cover the loss of the family that the government did to them in 1984 because ‘Bandaids does not fix the bullet holes.’

Nanavati Commission Report

The Justice G.T. Nanavati commission was a one-man commission headed by Justice G.T. Nanavati, a retired Judge of the Supreme Court of India, appointed by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in May 2000, to investigate the “killing of innocent Sikhs” during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots.The commission was mandated to submit its report within six months, but it took five years. The report in two volumes was completed in February 2005. The commission report details accusations and evidence against senior members of the Delhi wing of the then ruling Congress Party, including Jagdish Tytler, later a Cabinet Minister, MP Sajjan Kumar, and late minister H.K.L. Bhagat. They were accused of instigating mobs to avenge the assassination of Indira Gandhi by killing Sikhs in their constituencies. The report also held the then Lt. Governor PG Gavai for failing in his duty and late orders for controlling the riots. The Commission also held the then Delhi police commissioner S.C. Tandon directly responsible for the riots. There was a widespread protest against the report as it did not mention clearly the role of Tytler and other members of the Congress Party in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. The report led to the resignation of Jagdish Tytler from the Union Cabinet. A few days after the report was tabled in the Parliament, the Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh also apologized to the Sikh community for Operation Blue Star and the riots that followed. The report stated that Jagdish Tytler “very probably” had a hand in the riots.[6]

The report had been lambasted by the Congress dominated United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government but the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) accepted the report and criticized the Congress party as “guilty”

Legal And Judicial (In) Action

To this date and despite the establishment of three commissions and seven committees of inquiry in charge of investigating and probing various aspects of the pogrom, none of the main organizers of the pogrom have been prosecuted. The Indian judicial system failed to hold them accountable either on its own initiative or because of pressure by Congress parties and governments. In spite of prolonged trials, only 13 persons have been convicted and one of them was declared a proclaimed offender. Furthermore, some of the key instigators managed to go on with their political careers. For instance, Kamal Nath, H.K.L Bhagat, and Jagdish Tytler were all reelected in their respective constituency and were all given several cabinet minister positions.

After repeated refusals to set up a commission of inquiry, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi finally appointed in April 1985 RanganathMisra, a judge of the Supreme Court, as head of a commission in charge of inquiring «into the allegations in regards to the incidents of organized violence which took place in Delhi following the assassination of the late Prime Minister, Smt. Indira Gandhi» and recommending «measures which may be adopted for the prevention of recurrence of such incidents» (Misra, 1987: 1). A little earlier, a commission led by VedMarwah, additional commissioner of police, had been appointed in November 1984 to inquire into the role of the police during the pogrom. It was then stalled by the Central government and its records were selectively passed on to the next commission when the Misra Commission was set up. The Misra Report concluded that violence had been spontaneous; a result of the grief caused by Indira Gandhi’s assassination, and blamed it on the «lower classes» of society, which it held responsible because of its increasing criminalization. It then exonerated senior police officers and politicians by putting the blame on the subordinate ranks of the police, which were only accused of indifference. Moreover, it added that if Congress (I) workers had indeed participated in the killings, it was not as party members but in their personal capacity. Besides, another committee headed by Gurdial Singh Dhillon was appointed in 1985 to recommend measures for the rehabilitation of victims. It asked that the insurance claims of attacked business establishments be paid but the Central government rejected the claims. In February 1987, three more committees were appointed by the government on the basis of recommendations of the Misra Commission. Firstly, the Jain-Banerjee committee, which was subsequently replaced by the Potti-Rosha committee in March 1990 and then by the Jain-Aggarwal committee in December 1990, was charged to examine the registration and investigation of criminal cases, recommending the registration of cases, and monitoring the conduct of investigations. All looked at accusations against Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar and recommended cases to be registered against both. However, none was registered against them and the probe stopped in 1993. Secondly, the Ahooja committee had to establish the official number of deaths in the massacres. And thirdly, the Kapur-Mittal committee was in charge of further discussing the role of the police. Seventy-two policemen were identified for connivance or gross negligence and 30 were recommended for dismissal but no one was punished. Then, another committee, the Narula committee, was appointed in December 1993 by the Madhan Lal Khurana government in Delhi. It also recommended the registration of cases of some Congress (I)’s leaders such as H.K.L Bhagat, Sajjan Kumar, and Jagdish Tytler. However, it had once again no effect since no case was registered.

Finally, the last commission was set up in May 2000 by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) through a unanimous resolution passed at the Rajya Sabha. It was headed by Justice G. T. Nanavati, retired judge of the Supreme Court of India. Its terms of inquiry were nearly the same as Misra Commissions. The Nanavati report was submitted to the government in February 2005. Contrary to the Misra Commission, its procedure of inquiry was fully transparent and it acknowledged that violence from November 1 onwards was organized though it understated the scale of violence and failed to hold anyone accountable for it. The Nanavati Commission issued notices to H.K.L Bhagat, former Union Minister, DharamdasShastri, former Member of Parliament (MP), Kamal Nath (Union Commerce Minister at the time), and asked for the reopening of the cases against then MP Sajjan Kumar (Chairman Delhi Rural Development Board) and JagdishTytler (Union State Minister for Non-Resident Indians (NRI) at the time). However, the government refused to reopen these cases and the only consequence of this report was that the last two had to resign from their official position. Concerning Sajjan Kumar, the Nanavati Report stated, «The Commission is inclined to take the view that there is credible evidence against Sajjan Kumar and Balwan Khokhar for recording a finding that they were probably involved as alleged by witnesses», and recommended to the Union Government to «examine only those cases were witnesses have accused Sajjan Kumar specifically and yet no charge sheets were filed against him and cases were terminated as untraced» (Nanavati Report, 2005). In the Sultanpuri case alleging his involvement in the killing in Sultanpuri, the only 1984 riot case against Sajjan Kumar being probed by the CBI before it registered five more cases against him following the Nanavati Commission report in 2005, Sajjan Kumar was acquitted in December 2002, the trial judge trashing the CBI saying it had «miserably failed to prove the case». It took five years for the CBI to get its appeal against the acquittal admitted in the Delhi High Court and no charge sheet has been registered in the five other cases in four years. About JagdishTytler the Nanavati Report reads «Relying upon all this material, the Commission considers it safe to record a finding that there is credible evidence against Jagdish Tytler to the effect that very probably he had a hand in organizing attacks on Sikhs. The Commission, therefore, recommends to the government to look into this aspect and take further action as may be found necessary» (Nanavati, 2005). One of the cases against Tytler relates to an incident when a mob set afire GurudwaraPulbangash killing three persons. Both Surinder Singh, who was the head Granthi of Gurudwara Sahib MajnukaTilla, and Jasbir Singh, who was living in Delhi, categorically told the CBI they had seen Tytler instigating the mob and heard him telling his supporters on November 1, 1984, outside the Gurudwara: «Don’t only loot them but kill them. They have killed our mother». However, in its action-taken report, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government rejected these recommendations on the ground that «In criminal cases, a person cannot be prosecuted simply on the basis of probability».

Once again the truth about the anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi in 1984 was buried by the government and the survivors’ quest for knowledge, justice, and reparation stalled. The burial of the truth went on recently when the Criminal Bureau of Investigation (CBI) gave both Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar, Congress’ candidates for respectively Delhi north-eastern and southern constituencies, a clean chit allowing them to participate in the 15th Lok Sabha elections, on the ground that the testimonies of Surinder Singh, a self-proclaimed eyewitness, and Jasbir Singh, a California-based witness, were too inconsistent, unreliable and unworthy of credit.

However, the ghosts of 1984 resurfaced in the course of the electoral campaign when Jarnail Singh, a Sikh journalist, and Dainik Jagran’s defense correspondent, threw one of his shoes at Union Home Minister P. Chidambaram during a Congress press conference. This event propelled a wave of protest among the Sikh communities of Delhi and Punjab and many political observers also criticized the CBI for being patently non-independent and behaving like the handmaiden of the Congress government. This led to the removal of Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar, the last two recognizable public figures perceived to have led the mob to attack Sikhs following the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984 (others like H.K.L. Bhagat and Lalit Maken are long gone), as Congress’ candidates for the Lok Sabha elections. The two «offered to withdraw» from the contest in view of the controversy over their candidature which could have affected the Congress’ electoral prospects not only in the capital but also in Punjab.

As they wait for the charge sheets to continue, Congress once again only settled for temporary damage control for the sake of political exigency with no concern for the victims’ quest for justice. Notwithstanding the fact that Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, the first Sikh Prime Minister, called the riots a «national shame» in Parliament, Congress President Sonia Gandhi visited the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and Rahul Gandhi’s statement that the 1984 riots were «unfortunate and condemnable» were relatively well-received, the Congress party seems unable to learn from history and to understand that the ghosts of 1984 cannot be exercised unless the victims get full justice.

Who Are The Guilty?

- The social and political consequences of the Government’s stance during the carnage, its deliberate inaction, and its callousness towards relief and rehabilitation are far-reaching. It is indeed a matter of grave concern that the government has made serious inquiries into the entire tragic episode which seems to be so well planned and designed. It is curious that for the seven hours that the government had between the time of Mrs. Gandhi’s Assassination and the official announcement of her death, no security arrangements were made for the victims. The dubious role of the politicians belonging to the ruling party has been highlighted in various press reports. The government, under pressure, has changed a few faces by transfers and suspension of Junior officers. It is important that we do not all for this ploy, for our investigation reveals that these are only scapegoats.

In Popular Culture

- The Delhi riots have been the subject of several films and novels:-

The 2005 English film Amu, by Shonali Bose and starring Konkona Sen Sharma and Brinda Karat, is based on Shonali Bose’s novel of the same name. The film tells the story of a girl, orphaned during the riots, who reconciles with her adoption years later. Although it won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in English, it was censored in India but was released on DVD without the cuts.

The 2004 Hindi film Kaya Taran (Chrysalis), directed by Shashi Kumar and starring Seema Biswas, is based on the Malayalam short story “When Big Tree Falls” by S. Madhavan. The film revolves around a Sikh woman and her young son, who took shelter in a Meerut nunnery during the riots.

The 2003 Bollywood film Hawayein, a project of Babbu Maan and Ammtoje Mann, is based on the aftermath of Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the 1984 riots, and the subsequent victimization of the Punjabi people.

Mamoni Raisom Goswami’s Assamesenovel, Tej Aru DhulireDhusaritaPrishtha (Pages Stained with Blood), focuses on the riots.

Khushwant Singh and KuldipNayar’s book, Tragedy of Punjab: Operation Bluestar&After, focuses on the events surrounding the riots.

Jarnail Singh’s non-fiction book, I Accuse, describes incidents that occurred during the riots.

Uma Chakravarthi and NanditaHakser’s book, The Delhi Riots: Three Days in the Life of a Nation, has interviews with victims of the Delhi riots.

S. Phoolkaand human-rights activist and journalist Manoj Mitta wrote the first account of the riots When a Tree Shook Delhi.

HELIUM (a novel of 1984, published by Bloomsbury in 2013) by Jaspreet Singh]

The 2014 Punjabi film, Punjab 1984 with Diljit Dosanjh, is based on the aftermath of Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the riots, and the subsequent victimization of the Punjabi people.

The 2016 Bollywood film, 31st October with Vir Das, is based on the riots.

The 2016 Punjabi film, Dharam Yudh Morcha, is based on the riots.

In the 2001 Star Trek novel The Eugenics Wars: The Rise and Fall of Khan Noonien Singh by Gary Cox, a 14-year-old Khan, who is depicted as a North Indian from a family of Sikhs, is caught up in the riots while reading in a used book stall in NaiSarak. He is injured, doused with kerosene, and nearly set on fire by a mob before being rescued by Gary Seven.

Many Punjabi books such as ‘dairi de panne’(pages of the diary) depicted the eyewitness’s incidents during the riots. (A must-read book)

Its Time For India To Accept The Responsibility For Anti Sikh Riots 1984

1984 remains one of the darkest years in modern Indian history. In June of that year, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered a military assault on the most significant religious center for the Sikhs, Darbar Sahib (i.e., the Golden Temple) in Amritsar, Punjab. The attack killed thousands of civilians. On October 31, 1984, Mrs. Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

Her assassination triggered genocidal killings around the country, particularly in India’s capital city, New Delhi. TIME reported on the massacres just days after the violence subsided:

Frenzied mobs of young Hindu thugs, thirsting for revenge, burned Sikh-owned stores to the ground, dragged Sikhs out of their homes, cars, and trains, then clubbed them to death or set them aflame before raging off in search of other victims.

Witnesses watched with horror as the mobs walked the streets of New Delhi, gang-raping Sikh women, murdering Sikh men, and burning down Sikh homes, businesses, and Gurdwaras (Sikh houses of worship). Eyewitness accounts describe how law enforcement and government officials participated in the massacres by engaging in the violence, inciting civilians to seek vengeance, and providing the mobs with weapons.1984 remains one of the darkest years in modern Indian history. In June of that year, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered a military assault on the most significant religious center for the Sikhs, Darbar Sahib (i.e., the Golden Temple) in Amritsar, Punjab. The attack killed thousands of civilians. On October 31, 1984, Mrs. Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

Her assassination triggered genocidal killings around the country, particularly in India’s capital city, New Delhi. TIME reported on the massacres just days after the violence subsided:

Frenzied mobs of young Hindu thugs, thirsting for revenge, burned Sikh-owned stores to the ground, dragged Sikhs out of their homes, cars, and trains, then clubbed them to death or set them aflame before raging off in search of other victims.

Witnesses watched with horror as the mobs walked the streets of New Delhi, gang-raping Sikh women, murdering Sikh men, and burning down Sikh homes, businesses and Gurdwaras (Sikh houses of worship). Eyewitness accounts describe how law enforcement and government officials participated in the massacres by engaging in the violence, inciting civilians to seek vengeance, and providing the mobs with weapons.

The pogroms continued unabated, and according to official reports, within three days nearly 3,000 Sikhs had been murdered, at a rate of one per minute at the peak of the violence. Unofficial death estimates are far higher, and human rights activists have identified specific individuals complicit in organizing and perpetrating the massacres.

“Almost as many Sikhs died in a few days in India in 1984 than all the deaths and disappearances in Chile during the 17-year military rule of Gen. Augusto Pinochet between 1973 and 1990,” pointed out Barbara Crossette, a former New York Times bureau chief in New Delhi, in a report for World Policy Journal.

Thirty years later, those who survived the violence have yet to receive any semblance of justice. Most perpetrators have yet to be charged and held accountable for their crimes, and many of the affected families continue to live in poverty and disenfranchisement to this day. The Indian government’s formal position for three decades has been that accountability comes in the form of silence.

The Indian government is certainly not the first to massacre its own citizenry. Yet, as Crossette points out, so many of the nations complicit in ethnic cleansing – including Chile, Argentina, Rwanda, and South Africa – have recognized the importance of addressing past atrocities.

Yet the Indian state stubbornly refuses to admit its fault and take ownership of its participation in mass violence, despite enormous evidence to the contrary.

It would help if we started with the language.

The term commonly used to describe the anti-Sikh pogroms of 1984 is “riot.” The word riot is problematic because it implies random acts of disorganized violence. It invokes images of chaos that overwhelm law enforcement and the government that is there to protect its people.

The anti-Sikh violence of 1984 was not a riot. The massacres were not spontaneous, anomalous, or disorganized. According to a report belatedly commissioned by the Government of India in 2000, “but for the backing and help of influential and resourceful persons, killing of Sikhs so swiftly and in large numbers could not have happened.”

Our failure to properly define the problem has also meant that it has not received the appropriate response; neither the Indian government nor the international community has treated the violence for what it is – a crime against humanity.

If we were to accurately update the language we use to describe the anti-Sikh violence, maybe we could then finally begin a proper discussion about accountability and reparations. Acknowledging the malicious intent underlying the massacres is the first step toward reconciliation.

Although 30 years have now passed, India has a historic opportunity to make amends and seek reconciliation while those directly affected by the violence are still alive. It behooves the Indian state to seek closure on this issue, while the primary stakeholders – survivors and perpetrators alike – are around to reach a resolution. Until then, political stability will remain a challenge as minorities in India, including its more than 21 million Sikhs, will continue to feel alienated and targeted by their own government.

US Stand

In a jolt to a pro-Khalistan group in the US, the Obama administration refused to declare the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in India as genocide but noted that grave human rights violations had occurred. The White House response in this regard came months after a section of the Sikh community in the US launched an online petition campaign urging the Obama Administration to recognize the 1984 riots as genocide.

The petition created on November 15, 2012, generated more than 30,000 signatures within weeks. Each petition that crosses the threshold of 25,000 signatures is reviewed a receives a response.

It noted that the US State Department’s official country reports on Human Rights Practices, for example, covered the violence and its aftermath in detail, with sections on political killings, disappearances, denial of fair public trials, negative effects on freedom of religion, and the government’s response to civil society organizations investigating allegations of human rights violations.

Expressing disappointment over the response, the proponents of the petition in a statement said that the Obama administration “fails to take a position on Sikh genocide”.

“The response ignores the recent discoveries of mass graves of Sikhs killed during 1984 and falls short of taking a position on the issue of Genocide”, said a statement issued by Gurpatwant S Pannu, who heads the New York-based ‘Sikh for Justice’ group.

Role Of Media

The media, by nature, play an extremely important role in any socio-political situation irrespective of the boundary they hold (Mohanka, 2005). The media’s role in the riots of 1984 is an interesting case. Scholars believe that the media can play a role in focusing on a cause much before it takes an ugly turn. In the case of Punjab in 1984, the local media were not supportive of the Sikh causes. Moreover, since the beginning of the problems in Punjab, the government had strict control of the media and imposed heavy censorship. From independence until the invasion of cable television in India, electronic media had served as the mouthpiece of the government.

A joint statement of the Press Club of India (PCI) and the Indian Women’s Press Corps (IWPC) on February 25 noted that the “police were either absent or have not come to help”. This was a noteworthy feature, made noteworthy by the fact of overt police inaction, especially on February 24 and 25, when the violence had turned full-blown and was at its peak.

In fact, media accounts have hinted at police personnel aiding a section of the producers of communal violence. This aspect needs to be examined in depth by an impartial probe, whose terms of reference ought to go beyond capturing specific events and delve into underlying – and surrounding – social and political causes if basic truths are to be unearthed for future guidance on police administration, policing responsibilities and state orientation.

The PCI-IWPC joint statement had noted, “Shockingly, mobs were checking religious credentials of journalists.” The published account of a Times of India photographer, Anindyo Chattopadhyay, speaks of male journalists being made to lower their trousers to check religious identity. This again was a new feature. Mr. Chattopadhyay is a member of the PCI Managing Committee and his insights were useful in the preparation of this report, besides those of a clutch of reporters and photographers who helpfully gave us a sense of the atmosphere and the time-line as the trouble spread across a corner of Delhi.

In the 1984 riots in which innocent Sikhs had been targeted, the police had been found wanting. Police personnel had encouraged rampaging mobs in some instances. The senior police leadership had remained quiescent, as of February 2020. However, reporters and photographers had not been threatened and no particular bravery was called for on their part.

Was this in part due to the fact that the mobs in 1984 were amorphous in nature, though local figures linked to the then ruling party directed mob actions in their areas, while in contrast, the communal violence of 2020 appeared to be triggered – as widely reported and commented on – in the wake of provocative public comments of an influential ruling party personality who, just weeks earlier, had created an ‘India-Pakistan’ binary – a deplorable construct aimed a demeaning India’s largest religious minority – in the context of the Delhi Assembly election?

More, the ruling national party of today is able to intervene to further its political and ideological ends through a host of civil society outfits and networks that frontload the religious factor and frequently engage in uncivil conduct? Some of these, it is widely alleged, were acting upfront in the ‘India-Pakistan’ battle zones with devastating effects.

These appeared to be ideologically oriented mobs, not sundry mobs. Some loot and carry were apparently involved in both instances. But in 2020, it appears that one of the mob objectives was to economically cripple minority locations that were hit. Shops, godowns, and small manufactories were particularly targeted.

The violence commenced on February 23, raged on through February 24 and 25, and simmered and eventually petered out by February 26, although there was tension and anxiety in the air even on March 7 when the PCI president, Anand K. Sahay, visited some of the worst affected areas with colleagues to get a feel of the geography and social make-up of the communal battleground areas, and a sense of the public mood.

- Similar was the role of the electronic media in Punjab during the riots. The government had such tight control over the media that the foreign correspondents trying to capture the horrific events were not even allowed in the local land. The Indian government acted as a strict visible gatekeeper and made it impossible to approve journalist visas for foreign correspondents. The events of the 1984 riots thus suffered not only from biased media coverage but also selective coverage, which projected a one-sided, carefully selected perspective (Das, 2009). The “media blackout” during Operation Bluestar is a prime example of the same. The day before the actual invasion by the Indian Army, the government ordered all press out of the state and restricted press coverage in Punjab. The press was allowed only a week later on special organized guided tours. The aftermath was later described by the press as involving a small gang of criminals disliked by the majority of Sikhs and Indians. The press described the militants as petty political agitators rather than leaders of a movement for a greater Punjab autonomy, as believed by a majority of Sikhs. Similarly, during the reportage of the 1984 riots, there were discrepancy between the press release of data and images and the actual severity of the violent situation that prevailed in the streets of New Delhi (Das, 2009). This usage of selective information in the Indian media only contributed to the ambiguous image of Sikhs throughout the nation and failed to bring their plight to light. During the Sikh Movement, the government of India had passed the National Security Act (1980), the Punjab Disturbed Areas Ordinance (1983), The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (1983) and the Terrorists Affected Areas (Special Courts Act of 1984). These acts provided the police and army with sweeping powers. They could charge and curtail to the right to life under specific situations. The approach of the media during the crisis had been partisan in taking into account all types of multi-dimensional problem, historical, political, socio-economic and ideological. The media only focused on special restricted information and ignored a careful examination of all the issues and processes that had led to the mayhem and the riots. During 1984, Indian leaders were free to make up non-existent stories and broadcast through government-controlled radio and television channels. Since there was a major restriction on the foreign press, all foreign news correspondents were left with no choice but to take the twister news of the local government-controlled media.The national newspaper’s reporting on the Sikhs made no distinction between a regional political party, a handful of militants and the entire Sikh community. Even the senior editors and columnists of the national newspapers considered all Sikhs accountable for the assassination of Indira Gandhi and provided no sympathy to the community during the riots. Through the critical years of the political crisis in Punjab before the horrific riots, the national dailies had not help resolve the issue. The Times of India, one of the leading national dailies, and The Hindustan Times did more to incite hostility between Hindus and Sikhs than perhaps any other national English language newspaper (Das, 2009).The media were involved in the dissemination of misinformation to the public. The best example of the same would be when a national newspaper carried an article reporting that huge quantities of heroin and drugs had been recovered within the Golden Temple complex and the same had been used by the militants to illegally fund their operations. Since, the foreign press was banned in Punjab; they picked up the story based on the 14 June Press Trust of India (PTI) news report from government sources. This news was carried in the major international newspapers. One week into the incident, the government retracted the official report on the grounds that the drugs had been recovered from the India-Pakistan border and not the Golden Temple complex. This retraction by the government was not picked up by most international news agencies and the damage done by the initial report falsely remained among the masses.

Top 13 Interesting Facts About Anti-Sikh Riots

The riots broke out after the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards – Satwant Singh and Beant Singh – on October 31, 1984.

Groups of armed men targeted Sikhs across Delhi and attacked their houses and shops.

On November 1, armed mobs were seen on Delhi streets, gurudwaras were vandalized and innocent Sikhs were killed.

Sikhs in Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh were also targeted.

Former union minister HKL Bhagat, Congress leaders Jagdish Tytler, Congress lawmakers Sajjan Kumar, Lalit Makan, and Dharam Das Shastri, were some of the key accused in riots cases, for instigating mobs.

Massacre of Sikhs was planned in a meeting organized at 24 Akbar Road, New Delhi on October 31, 1984, attended by members of Parliament and senior members of the Congress party including Jagdish Tytler, Sajjan Kumar, Kamal Nath, Dharam Das Shastri, Vasant Sathe, HKL Bhagat, Lalit Makhen, and Arjun Das amongst others.

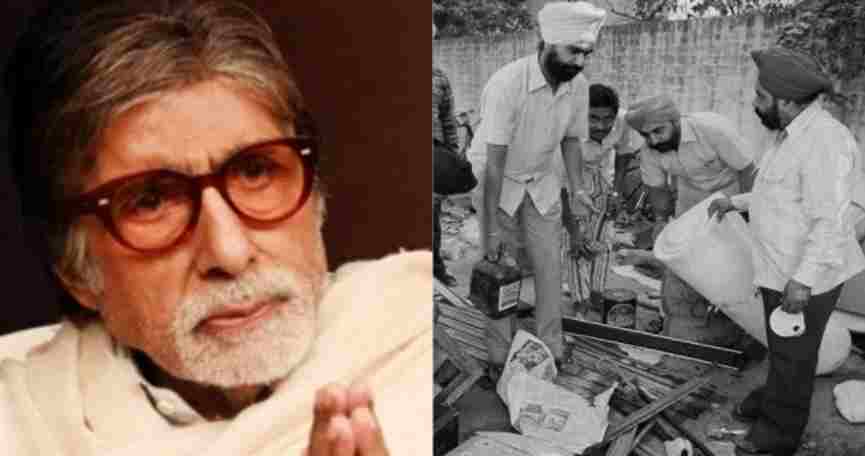

State media showed inflammatory speeches and scenes. Popular movie stars like Amitabh Bachchan are shown on state television raising slogans like “Khoon ka badla khoon” (blood for blood) and “Khoon ke chintey si khon ke ghartak pahunchni chahiye” (Splashes of blood should reach the doorsteps of Sikhs).

Police commandos from Police headquarters Madhuban, Haryana on the orders of Bhajan Lal, the then Chief Minister of Haryana send to commit the massacre of Sikhs.

Expert arsonists and professional goons were brought from outside and transported to different areas in Government buses. Supplied with inflammable materials to burn Sikhs, Sikh houses, businesses, and Sikh temples.

Police either actively participated in committing the massacre of Sikhs or stood as silent spectators while Sikhs were burnt alive. Police even supplied diesel from police jeeps to the arsonists. Police disarmed the Sikhs before mobs attacked them.

No curfew was imposed or an army was called while most of the killings took place. When the army called, deliberately designed to be ineffective.

After 25 years the organizers and perpetrators of the Genocide roam free and even enjoy positions of power. None were punished for the killings of the Sikhs.

Ten commissions have failed to bring Justice. Affidavits filed before commissions were found lying at the residences of those accused of organizing and committing the massacre.