Wall knocks are badminton’s most basic drill, and Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian was told by coach Aravindan Samiappan in Chennai to get on with hitting against the wall at age 6. It’s when the tiny boy, barely 4 feet, and not even managing to swing the racquet around the shuttle, got started at the Fireball Academy at Annanagar.

- Advertisement -

“It’s a basic drill, quite uninteresting. And kids often lose interest. But Sankar just did not waver. Everyone likes to attack, hit flat and fast, not him. He didn’t look left or right for 30 minutes. How that small kid had that focus I still don’t know,” coach Aravindan recalls.

On Saturday, the 18-year-old defensive metronome reached the Junior Badminton World Championship final, where he will take on Chinese Taipei’s Kuan Lin Kuo, after beating the most talked-about talent at Santander, Spain, Thailand’s Panitchapon Teeraratsakul 21-13, 21-15.

“He was the most feared because he had upset big names with big strokes. But the boy didn’t have patience at all so we stuck to sound defence, made him move and Sankar floated it around knowing he won’t last long,” Aravindan clucked.

- Advertisement -

Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian at a young age. (Special arrangement)

Those wall knocks had built reserves of patience that were in evidence in both pre-quarters and a 91-minute quarterfinal against a doughty Chinese on Friday. “Sankar loves playing rallies, always has. It’s his mindset. Most kids don’t like to defend because they get scared if 2-3 shuttles get retrieved. Sankar has a lot of trust in his defensive game,” the coach adds.

Japanese Kento Momota’s emergence internationally gave Sankar the reassurance that a rally game with good control could survive. “Many have said he won’t survive. And I agree, just defence is inadequate. He doesn’t have the smash power yet, but we’re not hanging back and relying on defence. The attack will develop. He looks up to Momota for confidence though he’s never doubted his style,” Aravindan assures.

- Advertisement -

During the pandemic, and on his way to becoming junior World No 1, Sankar would return to wall knocks. “For 3, 4, 5 hours! I was stunned. If you keep hitting against the wall for even 45 minutes, the forearm can go numb. It’s a basic, boring drill. But Sankar was undaunted,” the coach added.

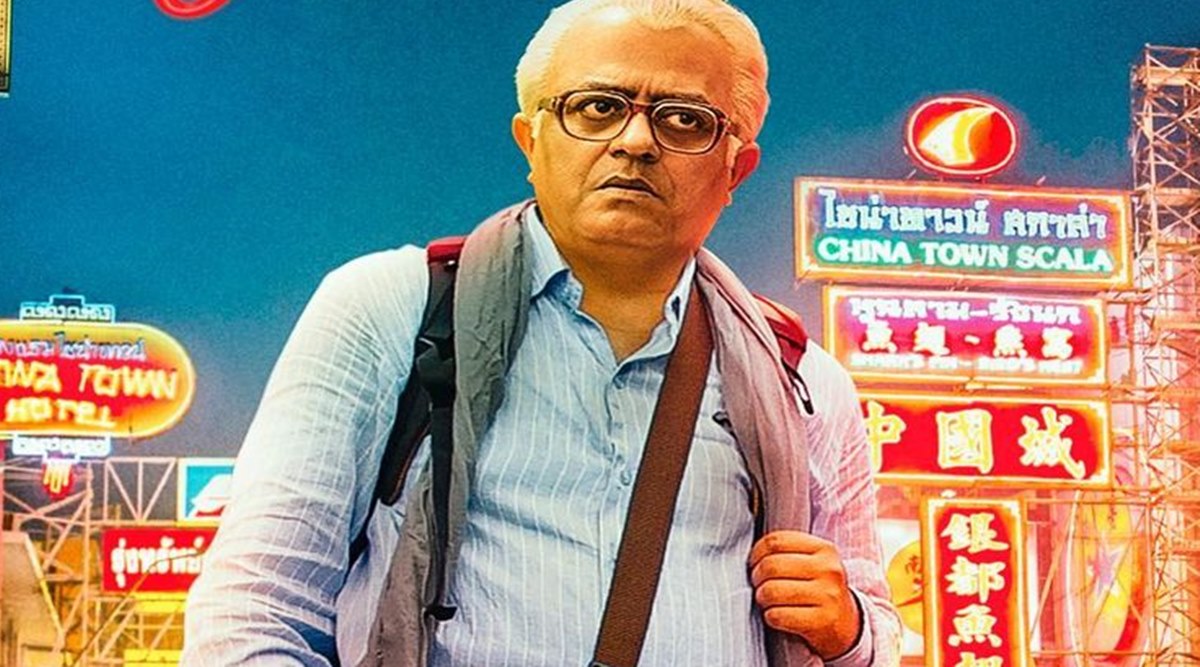

Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian. (Special arrangement)

Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian. (Special arrangement)

Against the Thai, Sankar would pick up every shuttle, forcing the attacking stroke maker to flee to hitting the lines. The errors would pile up with the shuttle straying wide or long, and very few winners per se from the Indian. But attack is not simply smashing power, Aravindan stresses. “It’s also counters and increasing pace and it’s Sankar’s fast retrieving game that troubles opponents.”

- Advertisement -

China’s Hu Zhen wasn’t as talented, but ready to grit it out. “Sankar had no clue till after one hour or the second half of the third game when he sensed the Chinese was tiring. It’s when tenacity and adrenaline kicked in.” Sankar is not as fit as many Indians his age, Aravindan concedes. “But everyone is fit in badminton! I believe technique and tactics are overrated. Only temperament matters in pressure situations. Sankar has that,” he says. “You need both physical and mental strength. We inculcate mental strength.”

- Advertisement -

The coach doesn’t believe in waking up at 6 am and training too hard. “Focus and intensity even if for 2 hours is important. I want every session to be fantastic and exciting even if gruelling. But we can do that at smaller academies. Big academies don’t have the luxury to customise training according to players and need to follow a process.” A boutique academy could cater to the ‘defensive freak.’

Sankar could nurture his defensive ways because the Chennai coach believed all training should be player-centric. “Most of my 30-40 players are taught the attacking game. But I knew this one needed different things.”

Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian is all smiles. (Special arrangement)

Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian is all smiles. (Special arrangement)

Aravindan admits Sankar is difficult to coach, mostly because he has to stand there and feed a lakh shuttles each month, mostly to the 18-year-old. “He’s restless and gets agitated if I’m late and demands commitment. I’m not saying he’s not obedient but you can’t keep him quiet. 99 per cent time I want to stop because I have a leg stump and a bad shoulder. But I’m also a competitor so I tell him ‘you have to bl***y die first. I won’t stop feeding. Yesterday, both he and the Chinese were gone, but Sankar’s mindset was to withstand pressure. I face it every day,” he mock-sulks.

Aravindan played badminton “only up to college state level.”

“Look. I won only college level, but I’m a good player ok! I’m nothing as a player, but I played five years of cricket in the third-fourth division of TNCA (Tamil Nadu Cricket Association). I’m (a) multisport (player). I was never hardworking or disciplined, so I ensure Sankar does those things. But I teach well and understand the game and feed a lakh shuttles,” he says.

Aravindan reckons ‘Lin Dan and Lee Chong Wei will never become good coaches’. “They won’t have motivation. Their big dreams are already fulfilled. If Gopichand had won 5-6 All Englands, he might not have the hunger to become a great coach I think. People like me who achieved nothing as players, we have that fire,” he says.

Sankar, whose father is Aravindan’s friend and retired from Port Trust to ferry him back and forth from the academy, feeds off that fire. He’s a sucker for more knowledge. “After beating the Thai, he said ‘what a talented player.’ Sankar has great self-awareness, knows what he lacks and never shows off. Even if he wins tomorrow, he won’t cut a cake or celebrate. He’ll just say – what next? Move forward.”

There’s always the next match to be won. Sankar Muthusamy Subramanian from Chennai – which ain’t Hyderabad or Bangalore – knows defence and rallying is a lifetime’s meditative pursuit of every shuttle. Keep on keeping on, is his motto.